Sonny Barger

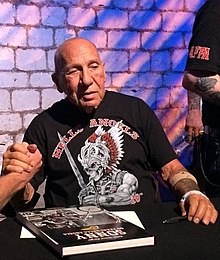

Sonny Barger | |

|---|---|

Barger in 1967 | |

| Born | Ralph Hubert Barger, Jr.[1] October 8, 1938 Modesto, California, U.S. |

| Died | June 29, 2022 (aged 83) Livermore, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Outlaw biker, author, actor |

| Known for | Founding member, Hells Angels Oakland chapter |

| Spouse(s) | Zorana (2005–2022; his death) |

| Allegiance | Hells Angels MC (1957–2022) |

| Conviction(s) | Possession of narcotics with intent to distribute (1973) Conspiracy to transport and receive explosives in interstate commerce with intent to kill and damage buildings (1988) |

| Criminal penalty | 10 years-to-life imprisonment (1973) 4 years imprisonment (1989) |

| Website | Official website |

Ralph Hubert "Sonny" Barger, Jr. (October 8, 1938 – June 29, 2022) was an American outlaw biker, author and actor who was a founding member of the Oakland, California chapter of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club in 1957.[2] He authored five books, and appeared on television and in film.

Early life

Ralph Hubert Barger, Jr. was born in Modesto, California, on October 8, 1938, the son of Kathryn Carmella (née Ritch) and Ralph Hubert Barger. His father had German and Dutch ancestry, and his mother was of Italian descent.[3][4] His mother left the family when Barger was four months old, leaving him and his older sister Shirley to be raised by their Pentecostalist grandmother and alcoholic father, a day laborer on the Oakland docks.[5][6] Growing up, Barger was suspended from school several times for assaulting teachers, and he often fought with other boys. He dropped out of school in the tenth grade. Although many of his school friends became drug addicts, Barger worked at a grocery store and enlisted in the U.S. Army, aged sixteen in 1955, but was given an honorable discharge fourteen months later when it was discovered that he had forged his birth certificate in order to be able to join. After his return from the Army, Barger drifted between menial jobs and lived with his father in a single residence at a hotel, later moving in with his sister and her children.[7]

Hells Angels

Barger joined his first motorcycle club, the Oakland Panthers, in 1956.[6] After that club disbanded, he started riding with another group of bikers, one of whom, Don "Boots" Reeves, wore a patch — a small skull wearing an aviator cap set within a set of wings — that belonged to a defunct motorcycle club in North Sacramento.[7] Founding their own club named the Hells Angels on April 1, 1957, each member wore the patch, later known as the Hells Angels' "Death's Head" logo, after having replicas made at a trophy store in Hayward. Barger and the Oakland Hells Angels were unaware at the time that there were several other, loosely affiliated, clubs using the same name throughout California. With Barger as president, the Oakland Hells Angels traveled to southern California and amalgamated with the other Hells Angels chapters, dividing territory and forming club bylaws. While infighting did take place between the chapters, conflicts predominantly arose with other clubs such as the Gypsy Jokers.[8]

With Otto Friedli, the founder of the original San Bernardino Hells Angels chapter, in prison, Barger was proclaimed de facto national president in 1958. One of his first actions was to relocate the club's "mother chapter" — the national headquarters — from San Bernardino to Oakland. Later that year, Barger suffered a fractured skull during a fight with Oakland police.[9] According to former Oakland Hells Angels chapter vice-president George "Baby Huey" Wethern — who later testified against the club and entered the Federal Witness Protection Program — in his 1978 book A Wayward Angel, Barger convened a meeting of the leaders of the Hells Angels and other California motorcycle clubs in 1960 in which the various clubs parleyed over the mutual problem of police harassment. The clubs voted to ally under a "one percenter" patch to be worn on their respective colors. The term refers to a comment allegedly made by the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) that 99% of motorcyclists were law-abiding citizens, implying the last one percent were outlaws.[9]

The Oakland chapter, with Barger serving as its president, assumed an informal position of authority within the Hells Angels that began following a standoff with local police and the California Highway Patrol in the aftermath of an outlaw motorcycle meeting in Porterville in September 1963.[8] The Oakland Hells Angels maintained a preeminent position as "first among equals" because it had the largest membership of any U.S. chapter and because of Barger's esteem among club members internationally.[10]

Barger was employed as a machine operator from 1960 to 1965, when he was dismissed due to extended absences. His criminal record began in 1963 after he was arrested for possession of marijuana. He was arrested again on the same charge the following year, and for assault with a deadly weapon in 1965 and 1966.[11] In the late 1960s, Barger began selling heroin and also developed an addiction to cocaine.[12] Between 1966 and 1973, the majority of his legitimate personal income was derived from advising various film projects.[9] Barger and the Angels became associated with the counterculture phenomenon of the 1960s.[1]

On October 16, 1965, six Hells Angels members were arrested and a police sergeant suffered a broken leg when a group of bikers attacked anti-Vietnam War demonstrators in Berkeley. The incident led to a collection of students, left-wing political groups, and labor unions led by Allen Ginsberg and Jerry Rubin meeting with motorcycle club representatives, headed by the president of the Sacramento HAMC chapter, in a cafeteria at San Jose State College, seeking assurance that a planned Vietnam Day Committee protest march in Oakland on November 20 would go undisturbed. On November 19, five Hells Angels led by Barger held a press conference at their bail bondsman's office, announcing that the club would not attend the protest the following day as "Any physical encounter would only produce sympathy for this mob of traitors", according to Barger.[13] He went on to read out a telegram sent to President Lyndon B. Johnson, reading "I volunteer a group of loyal Americans for behind the line duty in Vietnam. We feel that a crack group of trained guerillas could demoralize the Viet Cong and advance the cause of freedom."[14] President Johnson did not reply to the letter.[15]

For at least five years beginning in 1967, Barger and the Hells Angels turned over weapons acquired on the black market or locations of weapons, which could otherwise be used by Black Panther Party and Weather Underground radicals, to the Oakland Police Department (OPD) in exchange for the release of jailed Hells Angels members. OPD sergeant Edward "Ted" Hilliard testified in 1972 that he accepted guns, dynamite, and grenades from Barger personally in return for deals on arrests during at least fifteen separate meetings, the most recent of which took place in the spring of 1971.[16] Hilliard also testified that Barger had offered "to deliver the bagged body of a leftist for every Angel released from jail".[17] He denied, however, that authorities permitted crimes committed by the Hells Angels.[9]

Barger was among thirty-three members of the Oakland chapter arrested on drug charges after police raided a bar and a duplex apartment in the city on August 30, 1968. $7,000 worth of heroin and $2,500 worth of other narcotics were confiscated, as were firearms — including an M16 rifle, two shotguns, and an M1 carbine — and a large cache of ammunition, knives, chains, and suspected stolen merchandise.[18]

Barger was one of the Hells Angels present at the Rolling Stones' Altamont Free Concert on December 6, 1969, where concert goers and musicians alike were subjected to violence from the bikers, including Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane who was knocked unconscious and audience member Meredith Hunter who was stabbed to death. After the concert and critical media attention given to the HAMC, Barger went on a local California radio station to justify the actions of the Hells Angels and to present their side of the story. He claimed that violence only started once the crowd began vandalizing the Hells Angels' motorcycles. Barger would later claim that Hunter fired a shot that struck a Hells Angels member with what he described as "just a flesh wound."[19] He also claimed that he stuck a gun into Keith Richards' side, to force the Rolling Stones to keep on playing through the riot despite the band's misgivings.[20]

Trials and imprisonment

On April 11, 1970, Barger was arrested on narcotics charges after Donald Howarth, a film studio property manager and 1967 Mr. America from Studio City, was apprehended while walking towards Barger's home with 17 ounces of cocaine and 30 ounces of heroin (with an estimated retail worth of $350,000) in a suitcase. Barger temporarily resigned as president of the Oakland chapter in June 1970 to fight the charges, but returned to the position within months after his successor, John "Johnny Angel" Palomar, was sentenced to a ten-year prison term for shooting a bartender.[12] The drug charges against Barger were later dismissed, although Howarth was convicted and sentenced to serve five years-to-life in prison.[21] Barger was, however, sentenced to ninety days in jail after walking out of a court session.[11]

Barger and four other Hells Angels were charged with attempted murder, kidnapping, and assault with a deadly weapon after being arrested while driving through Redwood Regional Park by park rangers who discovered two bound, gagged and beaten club prospects in the trunk of the vehicle on January 22, 1972.[22] All five pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of unlawful imprisonment.[21]

Along with fellow Hells Angels members Sergey Walton, Donald Duane "Whitey" Smith, and "Oakland" Gary Popkin, Barger was charged with the May 21, 1972 murder of Servio Winston Agero — a drug dealer from McAllen, Texas who had traveled to Oakland with a consignment of narcotics for sale — which allegedly occurred following a dispute over an $80,000 cocaine deal. A prosecution witness, Richard Ivaldi, testified that he witnessed Barger shoot Agero dead as he slept at the home of an absent acquaintance, and that Barger subsequently ordered the others to set fire to the residence.[23] Barger and his three co-defendants were acquitted on December 29, 1972, following a seven-week trial after Ivaldi's credibility came under scrutiny.[12]

On March 16, 1973, Barger was sentenced to a prison term of ten years-to-life after he was convicted of possession of narcotics for sale (37 grams of heroin), and possession of a weapon by a convicted felon. His girlfriend, Sharon Gruhlke, was a co-defendant; her case ended in a mistrial when a jury failed to reach a verdict.[12] According to police intelligence reports, Barger had designated San Jose chapter president Fillmore Cross as his international successor during a motorcycle run at Bass Lake prior to his imprisonment.[21] Cross was also imprisoned, for possession of amphetamines in 1975, however, and Barger allegedly continued to lead the Hells Angels from his cell at Folsom State Prison.[22] He was paroled on November 3, 1977, after serving four-and-a-half years of his sentence.[24]

Barger was arrested on a parole violation charge of possession of firearms when police officers discovered a 9 mm semiautomatic pistol, a .38 caliber revolver, and a rifle after arriving at his Oakland home on March 27, 1978, to serve a subpoena and to conduct a parole search.[22] The case was dismissed when Barger's wife Sharon testified that the guns belonged to her, not her husband.[25]

Barger and his wife were among thirty-three members and associates of the Hells Angels' Oakland, San Francisco, Marin County, San Jose, Los Angeles, and Vallejo chapters indicted on Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act statutes on June 13, 1979.[25][26] The prosecution team, representing the federal government, attempted to demonstrate a pattern of behavior to convict Barger and other members of the club of racketeering offenses related to illegal weapons and drugs.[8] On July 2, 1980, following an eight-month trial in which 194 witnesses testified, a mistrial was declared when a jury failed to reach a verdict on counts against eighteen defendants. Of the remaining twelve, nine were convicted and three — including Sonny and Sharon Barger — were acquitted.[27] Barger repeatedly maintained that the club should not be held accountable for the actions of individual members.[1]

In 1983, Barger was diagnosed with throat cancer and temporarily handed control of the club over to his second-in-command, Michael O'Farrell, while he received and recovered from treatment.[9][28]

On November 10, 1987, thirteen Hells Angels including Barger were arrested on narcotics, weapons, explosives, and conspiracy charges during a series of raids carried out by the FBI, ATF, and California State Police in the San Francisco Bay Area, which also resulted in the seizure of over a hundred weapons, more than $1 million in cash and drugs, and three methamphetamine laboratories.[29] The operation in the Bay Area was executed in synchronization with raids on various other HAMC chapters in four other states — producing a total of thirty-eight arrests — and concluded a two-year FBI investigation of the club, which commenced in 1985 after Anthony John Tait, sergeant-at-arms of the Anchorage, Alaska Hells Angels chapter, volunteered to become a paid informant. Traveling the country at government expense, Tait made documented purchases of weapons, explosives, and drugs from the Hells Angels.[30] He also covertly recorded club meetings by wearing a wire.[31] During one such meeting, Barger admiringly told Tait he represented the "Hells Angel of the '90s" — clean-cut, articulate, and able to get club business done.[32] Barger and nine other Hells Angels from California and Alaska were extradited to Louisville, Kentucky to face trial for conspiring to transport firearms and explosives across state lines in order to kill members of the Outlaws Motorcycle Club in retaliation for the death of John Cleave Webb, the Anchorage HAMC chapter president who was shot and killed by two Outlaws members outside a biker bar in Jefferson County, Kentucky on August 12, 1986.[33] Barger was convicted of conspiracy on October 28, 1988, and was sentenced to a four-year prison term the following year.[9][34][35]

Subsequent years

Barger was released from FCI Phoenix in Arizona on November 6, 1992, after serving three-and-a-half years of a four-year sentence.[9][36] To celebrate the end of his parole, he held a private party in Livermore on November 6, 1994, which was attended by approximately 700 guests, including the politicians Gary Condit and Ben Nighthorse Campbell.[37][38] Colorado state senator Nighthorse Campbell had allegedly tried to use his influence to have Barger released from prison earlier.[32] In 1998, Barger returned to Arizona to join the Hells Angels' Cave Creek chapter.[8] The club was established in the state the year before following a "patch over" of the Dirty Dozen Motorcycle Club, which was promulgated during a meeting in Oakland in October 1997.[39]

Barger was present at the Hellraiser Ball, a tattoo and motorcycle trade exposition in Plainview, New York sponsored by the Long Island chapter of the HAMC, which was ambushed by dozens of members of the rival Pagan's Motorcycle Club on February 23, 2002, resulting in one biker being killed and at least ten injured.[40][41] A Hells Angels member was charged with second-degree murder and seventy-three Pagan members were indicted on federal racketeering charges in the aftermath of the incident.[42] Increasing tensions between the Hells Angels and other motorcycle clubs led to Barger organizing a peace conference scheduled to be held in the Arizona desert following the April 2002 Laughlin River Run motorcycle rally in Laughlin, Nevada. The meeting was canceled, however, as a result of the River Run riot, a confrontation between members of the Hells Angels and the Mongols Motorcycle Club at the rally which ended with three deaths.[43]

Barger left Arizona in October 2016, returning to the Oakland chapter.[44] On May 3, 2018, he testified in the racketeering trial of Bandidos Motorcycle Club former national president Jeffrey Fay Pike and former vice-president Xavier John Portillo after being called as a defense witness by lawyers for Pike. Unable to travel to the trial in San Antonio, Texas due to medical reasons, Barger testified via video link from the federal courthouse in San Francisco, denying that the Hells Angels and the Bandidos were enemies. Barger's testimony challenged earlier assertions by government witnesses who testified that Anthony Benesh, a motorcyclist who was shot dead in Austin, Texas on March 18, 2006, after attempting to establish a Hells Angels chapter in the city, was killed by Bandidos members because he had ignored the club's warnings to not set up a HAMC chapter in Texas.[45]

Television, film and writing

Barger features prominently in Hunter S. Thompson's book, Hell's Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (1966). Barger and the Hells Angels are also depicted in Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), during Ken Kesey's La Honda encampment. He appears in the documentary film about the Altamont Free Concert: Gimme Shelter (1970). Onscreen, Barger was identified but did not speak in Hells Angels on Wheels (1967) and was one of several members of the Angels who had speaking parts playing themselves in Hell's Angels '69 (1969); he appeared in several additional films.

In 2000, Barger became a bestselling author with his autobiography, Hell's Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club. He subsequently wrote several biker-related novels.[46] In later years, Barger worked to promote motorcycle safety: he co-authored a book on the subject with Darwin Holmstrom (the author of The Complete Idiot's Guide to Motorcycles (1998)[47]) titled Let's Ride: Sonny Barger's Guide to Motorcycling (2010).[48]

In terms of pure workmanship, personally I don't like Harleys. I ride them because I'm in the club, and that's the image, but if I could I would seriously consider riding a Honda ST1100 or a BMW. We really missed the boat not switching over to the Japanese models when they began building bigger bikes. I'll usually say "Fuck Harley-Davidson." — Ralph "Sonny" Barger, Hell's Angel [49]

On November 30, 2010, Barger made a guest appearance as Lenny "The Pimp" Janowitz on the season 3 finale of the FX television series Sons of Anarchy, about a fictional outlaw motorcycle club, allegedly based on the Hells Angels. Show creator Kurt Sutter spent time with Barger and other members of Hells Angels researching for the show, and acted opposite Barger in his scene. Barger returned on November 29, 2011, in the season 4 finale, part one. Barger's third guest appearance on Sons of Anarchy was during season 5, episode 10, which aired on November 13, 2012.

Personal life

Barger's first wife Elsie Mae (née George) died on February 1, 1967, from an embolism in her bloodstream after undergoing an illegal abortion. In 1969, he began a relationship with Sharon Gruhlke, a former beauty queen from Livermore.[12] Barger married Gruhlke while he was incarcerated at Folsom State Prison in 1973.[50] The marriage ended in divorce.[6]

In 1983, Barger was diagnosed with throat cancer after years of heavy smoking.[6] His diagnosis and treatment took place at Fort Miley VA Hospital in San Francisco. Having stage III laryngeal cancer, a total laryngectomy with bilateral functional neck dissections was performed by Michael Tralla MD, FACS. Consequently, due to his vocal cords being removed, Barger learned to vocalize using the muscles in his esophagus.[9]

In 1998, Barger returned to Arizona, where he had previously served a prison sentence, with his third wife Beth Noel (née Black) and stepdaughter Sarrah. He joined the Hells Angels' Cave Creek chapter, and operated a motorcycle repair shop.[6][8][51]

On March 7, 2003, Barger was arrested by Maricopa County Sheriff's Office deputies after a reported domestic dispute with his wife, Noel, and stepdaughter, Sarrah, at their home in New River, Arizona. Noel suffered a broken rib and back, and a lacerated spleen.[52] Barger was sentenced to an eight-day jail term for aggravated assault.[53] He and Noel later divorced.[6]

He married his fourth wife, Zorana (née Katzakian), on June 25, 2005.[54] He remained married to Zorana until he died in 2022.[1]

Barger underwent surgery as a result of prostate cancer in 2012. His prostate was removed and he was subsequently declared free of cancer.[55]

Death

On June 29, 2022, Barger died after a battle with liver cancer aged 83. He died peacefully in his home in Livermore, California.[56][57][6] His death was announced in a Facebook post reading:

If you are reading this message, you'll know that I'm gone. I've asked that this note be posted immediately after my passing.

I've lived a long and good life filled with adventure. And I've had the privilege to be part of an amazing club. Although I've had a public persona for decades, i've mostly enjoyed special time with my club brothers, my family, and close friends. Please know that I passed peacefully after a brief battle with cancer. But also know that in the end, I was surrounded by what really matters: My wife, Zorana, as well as my loved ones. Keep your head up high, stay loyal, remain free, and always value honor.

Sonny

Selected works

- With Keith Zimmerman (2001). Hell's Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell's Angels Motorcycle Club. William Morrow. ISBN 0-06-093754-8.

- Ridin' High, Livin' Free: Hell-Raising Motorcycle Stories. William Morrow. 2003. ISBN 0-06-000603-X.

- Dead in 5 Heartbeats. HarperTorch. 2004. ISBN 978-0-06-053253-6.

- Freedom: Credos from the Road. William Morrow. 2005. ISBN 0-06-053256-4.

- 6 Chambers, 1 Bullet. William Morrow. 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-074531-8.

- Let's Ride: Sonny Barger's Guide to Motorcycling. William Morrow. 2010. ISBN 978-0-06-196427-5.

Filmography

- Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967)[59]

- Hell's Angels '69 (1969)[59]

- Gimme Shelter (1970)

- Hell's Angels Forever (1983), featuring Sonny Barger, Jerry Garcia, Scott Barnes, Johnny Paycheck, Willie Nelson[60]

- Sons of Anarchy television series, (2010–2012), played recurring character Lenny "The Pimp" Janowitz[60]

- Dead in 5 Heartbeats (2012)[61][62][63]

References

- ^ a b c d e Sonny Barger, Face of the Hells Angels, Dies at 83 Daniel Victor, The New York Times (June 30, 2022) Archived June 30, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Newton-Matza, Mitchell (March 26, 2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History [2 volumes]. ISBN 978-1-61069-166-6.

- ^ Veno, Art (March 29, 2011). Brotherhoods. ISBN 9781459616110.

Born in Oakland in 1938 to a German-Dutch father and an Italian mother, he was nicknamed 'Sonny' according to the tradition of a first-born Italian son.

- ^ Barger, Sonny (October 13, 2009). Hell's Angel: The Autobiography Of Sonny Barger. ISBN 0061847364.

If there's one thing— and one thing only—I can thank my mother for, it is the shred of Italian upbringing she left behind.

- ^ Hell Hasn't Frozen Over Yet Susan Carpenter, Los Angeles Times (May 17, 2000) Archived July 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g Sonny Barger, biker outlaw and founder of Hells Angels, dies at 83 Paul W. Valentine The Washington Post (June 30, 2022) Archived July 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Hell's Angels Criminal Enterprise Albert De Amicis, University of Phoenix (August 14, 2009) Archived July 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Hell's Angel: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and The Hell's Angels Motorcycle Club Ralph 'Sonny' Barger, with Keith and Kent Zimmerman (2000) Archived July 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h Look Homeward Angel: Cycle Icon Sonny Barger Kick-Starts Life As A Free Man By Violating Parole Philip Martin, Phoenix New Times (December 2, 1992) Archived July 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Outlaw motorcycle gangs – USA overview National Institute of Justice (1991) Archived January 23, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Hell's Angels on Trial: Tales of Drugs & Death Tim Findley, Rolling Stone (December 21, 1972) Archived July 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Jail Terms Deplete Ranks of Hell's Angels Wallace Turner, The New York Times (March 18, 1973) Archived July 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hells Angels vs. Allen Ginsberg: The unlikely Vietnam War-era confrontation Bill Van Niekerken, San Francisco Chronicle (May 15, 2018) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ralph "Sonny" Barger Confronts VDC / Press Conference sfsu.edu Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Angels, Protesters and Patriots: What a Long-Ago Skirmish Says About Love of Country Chris A. Smith, California Magazine (Spring 2016) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Angels in Court: The Strange Tale of Baby Huey Tim Findley, Rolling Stone (February 15, 1973) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cummins, Eric (February 1994). The Rise and Fall of California's Radical Prison Movement. ISBN 9780804722322.

Oakland police sergeant Ted Hilliard testified in 1972 that the Hell's Angels bought weapons and explosives on the black market for the Oakland police in the late 1960's and that Barger offered "to deliver the bagged body of a leftist for every Angel released from jail".

- ^ 33 Angels Seized In Drug Roundup Oakland Tribune (August 31, 1968) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Barger, Sonny; Zimmerman, Keith; and Zimmerman, Kent Hell's Angels: The Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club. HarperCollins, pp 159–169

- ^ "Sonny Barger obituary". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ a b c Wayward Angel: The Full Story of the Hells Angels George Wethern and Vincent Colnett (1978)

- ^ a b c Hell's Angels: Masters of Menace Howard Kohn, Rolling Stone (April 5, 1979) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Death Scene Told at Angel Trial Del Lane, Oakland Tribune (November 22, 1972) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Barger Uncertain Of His Future Santa Cruz Sentinel (November 4, 1977) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b U.S. Drug Investigation Brings a Round of Arrests for Hell's Angels Wallace Turner, The New York Times (June 18, 1979) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hell's Angel racketeering defendants reduced by two Santa Maria Times (October 6, 1979) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mistrial Declared in 8-Month Hells Angels Trial on Coast Wayne King, The New York Times (July 3, 1980) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hells Angels Stage Funeral for Leader Killed in Bar Fight Los Angeles Times (June 11, 1989) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Five-state sweep produces arrests of 32 Hells Angels Ray Means, United Press International (November 11, 1987)

- ^ FBI report says informant uncovered Hells Angels crimes United Press International (December 5, 1987)

- ^ United States of America v. Ralph Hubert Barger Justia (October 5, 1990) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Angels in Arizona Karen Brande, Tucson Weekly (August 15, 1996) Archived March 26, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Louisville trial gives bikers an easy ride Michael York, The Washington Post (October 23, 1988) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jury Finds National Hells Angels Leader Guilty of Conspiracy Associated Press (October 29, 1988) Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Jury Finds Hells Angels Leader Guilty in Plots", Los Angeles Times, Associated Press, October 29, 1988 Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Inmate locator Federal Bureau of Prisons

- ^ Harley-riding senator says bikers get bum rap Deseret News (November 9, 1994) Archived July 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Actual Malice: A True Crime Political Thriller Breton Peace and Gary Condit (2016) Archived July 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chico Mora Led the Dirty Dozen Into the Hells Angels' Camp, Claiming Arizona for the Red and White Stephen Lemons, Phoenix New Times (June 24, 2015) Archived July 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Biker killed in gang fight at Hellraiser Ball Rupert Cornwell, The Independent (February 25, 2002) Archived July 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 'Hellraisers' brawl: L.I. biker-gang rumble leaves 1 dead, 10 hurt Lisa Pulitzer, New York Post (February 24, 2002)

- ^ Pagan Bikers Indicted in Brawl Frank Eltman, Associated Press (March 13, 2002)

- ^ Turf war heats up among biker gangs Archived December 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Lawrence Journal-World (May 4, 2002)

- ^ Open Road? Craig Outhier, Phoenix (February 21, 2018)

- ^ A founder of the Hells Angels testifies for ex-Bandidos leader Guillermo Contreras, San Antonio Express-News (May 3, 2018)

- ^ Hells Angels marks milestone Angela Hill, East Bay Times (March 30, 2007)

- ^ Holmstrom, Darwin (1998). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Motorcycles. Alpha.

- ^ Barger & Holmstrom (June 8, 2010). Let's Ride: Sonny Barger's Guide to Motorcycling. HarperCollins.

- ^ Barger, Ralph (October 2, 2001) [2001, 2000]. "Harleys, Choppers, Full Dressers, and Stolen Wheels". Hell's Angel the Life and Times of Sonny Barger and the Hell's Angels Motorcycle Club. Harper. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-06-093754-6.

- ^ The Rough Rider : Entrepreneur. Philanthropist. Hell's Angel Sonny Barger is just a regular guy. Unless you cross him. Bob Sipchen, Los Angeles Times (December 14, 1994)

- ^ Still on the road The Guardian (June 14, 2000)

- ^ Biker Gangs and Organized Crime Thomas Barker (2007)

- ^ Devilish Angels seek to look innocent Dennis Wagner and Senta Scarborough, The Arizona Republic (July 9, 2003)

- ^ Zorana Barger MyHeritage Archived July 6, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ American Legend Sonny Barger celebrate his 80. Birthday backroad-diaries.de (October 9, 2018)

- ^ "Hells Angels founder Sonny Barger dies at 83". NBC News. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Gartrell, Nate (June 29, 2022). "Sonny Barger, famous Hells Angel and bestselling author, dead at 83 of cancer". The Mercury News. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Hells Angels motorcycle club leader Sonny Barger dies at age 83 Victoria Bekiempis, The Guardian (30 June 2022) Archived 30 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Nathan Southern. "Sonny Barger: Full Biography". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ a b Sonny Barger at IMDb

- ^ "Deadin5Heartbeats". Deadin5Heartbeats.

- ^ "Dead in 5 Heartbeats (2013) — IMDb" – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ Blitz, Stefan (February 21, 2013). "DEAD IN 5 HEARTBEATS (movie review)".

Further reading

- "Authorities Crack Down on 'Angels'". Bangor Daily News. Associated Press. June 14, 1979. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- "Hells Angels Leader Leaves Jail". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 2, 1980. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- Bryant, Nick (October 5, 2000). ""Hell's Angel" interview (audio)". Salon.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2007.

- Martin, Phillip (December 2, 1992). "Look Homeward Angelcycle Icon Sonny Barger Kick-Starts Life as a Free Man by Violating Parole". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- Stillman, Deanne (July 10, 2000). "Hell's author; Legendary bad-ass biker Sonny Barger and his roaring Harley are burnin' up the highways on a ... uh ... book tour?". Salon.com.

External links

About the page

Presented content of the Wikipedia article was extracted in 2022-07-11 based on https://en.wikipedia.org/?curid=1136644