Samuel Alito

Samuel Alito | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2007 | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| Assumed office January 31, 2006 | |

| Nominated by | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Sandra Day O'Connor |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit | |

| In office April 30, 1990 – January 31, 2006 | |

| Nominated by | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | John Joseph Gibbons |

| Succeeded by | Joseph A. Greenaway Jr. |

| United States Attorney for the District of New Jersey | |

| In office December 10, 1987[1] – April 30, 1990 | |

| President | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Greelish |

| Succeeded by | Michael Chertoff |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Samuel Anthony Alito Jr. April 1, 1950 Trenton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Spouse(s) | Martha-Ann Bomgardner

(m. 1985) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1972–1980 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Signal Corps (Reserve) |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

|

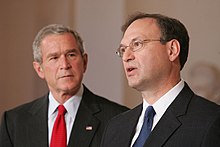

Samuel Anthony Alito Jr. (/əˈliːtoʊ/ ə-LEE-toh; born April 1, 1950) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George W. Bush on October 31, 2005, and has served since January 31, 2006.[2] He is the second Italian-American justice to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court, after Antonin Scalia, and the eleventh Roman Catholic.

Raised in Hamilton Township, New Jersey, and educated at Princeton University and Yale Law School, Alito served as the U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey and a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit before joining the Supreme Court. He is the 110th justice.

In 2013 Alito was considered "one of the most conservative justices on the Court".[3] He has described himself as a "practical originalist".[4] Alito's majority opinions in landmark cases include McDonald v. Chicago, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, Murphy v. NCAA, and Janus v. AFSCME.

Biography

Early life and education

Alito was born in Trenton, New Jersey, the son of Samuel A. Alito Sr., an Italian immigrant, and Rose Fradusco, an Italian-American.[5][6] His grandparents came from Roccella Ionica, Calabria and Palazzo San Gervasio, Basilicata, in southern Italy.[7] Alito's father earned a master's degree at Rutgers University and was a high school teacher and later the first Director of the New Jersey Office of Legislative Services, a state government position he held from 1952 to 1984. Alito's mother was a schoolteacher. Both are deceased.[8]

Alito grew up in Hamilton Township, New Jersey, a suburb of Trenton.[9] He attended Steinert High School where he graduated in 1968 as the class valedictorian,[10] and graduated Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude from Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs in 1972, completing a senior thesis titled "An Introduction to the Italian Constitutional Court" under the supervision of Walter F. Murphy.[11]

At Princeton, Alito chaired a student conference in 1971 called "The Boundaries of Privacy in American Society" which, among other things, supported curbs on domestic intelligence gathering and anticipated the need for a statute and a court to oversee national security surveillance.[12] The conference report itself also called for the decriminalization of sodomy, and urged for an end to discrimination against gays in hiring by employers. "Though Alito's name is attached to the chair's report, it remains unclear to what extent the report represented his personal opinions. Alumni, who served as 'commissioners' for the junior conference Alito chaired, offered conflicting information on how best to interpret the report."[13] Alito also led the American Whig-Cliosophic Society's Debate Panel during his time at Princeton.[14] He avoided Princeton's eating clubs, joining Stevenson Hall instead.[15]

While a sophomore at Princeton, Alito received a low lottery number, 32, in the Selective Service drawing on December 1, 1969.[16] In 1970, he became a member of the school's Army ROTC program, attending a six-week basic training camp that year at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Alito was a member of the Concerned Alumni of Princeton, which was formed in October 1972 at least in part to oppose Princeton's decisions regarding admitting women. Apart from Alito's written 1985 statement of membership in CAP on a job application, which he says was truthful, there is no other documentation of Alito's involvement with or contributions to the group. Alito has cited the banning and subsequent treatment of ROTC by the university as his reason for belonging to CAP.

Alito was commissioned a second lieutenant in the United States Army Reserve in 1972.[16] He began his military duty after graduating from law school in 1975 and served on active duty from September to December while attending the Signal Officer Basic Course at Fort Gordon, Georgia.[16] Alito was promoted to first lieutenant and captain, and completed his service obligation as a member of the inactive reserve before receiving his honorable discharge in 1980.[16]

At Princeton, Alito was "almost alone" in his familiarity with the writings of John Marshall Harlan II[17] and was much influenced by the course on constitutional interpretation taught by Walter F. Murphy, also his faculty adviser.[17] During his senior year at Princeton, Alito moved out of New Jersey for the first time to study in Italy, where he wrote his thesis on the Italian legal system.[18] Graduating in 1972, Alito left a sign of his lofty aspirations in his yearbook, which said that he hoped to "eventually warm a seat on the Supreme Court".[19]

Alito then attended Yale Law School, where he served as an editor of the Yale Law Journal and earned a Juris Doctor in 1975.

Early legal career

After graduating from law school, Alito clerked for Third Circuit appeals judge Leonard I. Garth in Newark, New Jersey in 1976 and 1977.[18] He interviewed with Supreme Court Justice Byron White for a clerkship but was not hired.[20] Between 1977 and 1981, Alito was Assistant United States Attorney, District of New Jersey. There he served under chief of the appeals division Assistant U.S. Attorney, later federal circuit judge, Maryanne Trump Barry.[21] (Barry and Alito later served alongside each other as judges on the Third Circuit.) While an Assistant U.S. Attorney for New Jersey, he prosecuted many cases involving drug trafficking and organized crime.[22]

From 1981 to 1985, Alito was Assistant to U.S. Solicitor General Rex E. Lee. In that capacity he argued 12 cases before the Supreme Court for the federal government.[23] In Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists (1986), the Supreme Court ruled against Charles Fried after he rejected a memo by Alito urging the Solicitor General to avoid directly attacking the constitutional right to an abortion.[24] Alito lost only two of the cases he argued before the Supreme Court.[25]

From 1985 to 1987, Alito was Deputy Assistant Attorney General under Charles J. Cooper in the Office of Legal Counsel during the tenure of Attorney General Edwin Meese. John F. Manning worked under Alito there.[15] Between 1986 and 1987, Alito authored nearly 470 pages of memorandums, in which he argued for expanding his client's law enforcement and personnel authorities.[26] In his 1985 application for Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Alito espoused conservative views, naming William F. Buckley, Jr., the National Review, Alexander Bickel, and Barry Goldwater's 1964 presidential campaign as major influences. He also expressed concern about Warren Court decisions in the areas of criminal procedure, the Establishment Clause, and reapportionment.[27]

From 1987 to 1990, Alito was the United States Attorney for the District of New Jersey. When he arrived, the office had begun the prosecution of 20 defendants accused of being mob affiliates of Anthony Accetturo.[28] In August 1988, the two-year trial, then the longest federal criminal trial in history, ended in the acquittal of all 20 after less than two days of jury deliberations.[29] Alito soon hired Michael Chertoff as his chief deputy.[29]

After an FBI agent was shot in the line of duty in 1988, Alito personally handled the trial, assigning himself the then-novice Stuart Rabner as an assistant, and securing the shooter's conviction.[29] In March 1988, Alito sought a rehearing of extradition proceedings against two Indian men, represented by Ron Kuby, who were accused of being terrorist assassins, after Alito discovered that the death threats his prosecutor had received had been sent to her by herself.[30] The prosecutor was later found not guilty of obstruction of justice by reason of insanity, after psychiatrists found she was a possible schizophrenic with up to four distinct personalities.[29][31] In 1989, Alito prosecuted a member of the Japanese Red Army for planning a terrorist bombing in Manhattan.[32]

Career as Adjunct Professor

As adjunct professor at Seton Hall University School of Law in Newark from 1999 to 2004, Alito taught courses in constitutional law and an original course on terrorism and civil liberties. In 1995, he was presented with the school's Saint Thomas More Medal "in recognition of his outstanding contributions to the field of law".[33] On May 25, 2007, he delivered the commencement address at Seton Hall Law's commencement ceremony and received an honorary law degree from the school.[34]

Alito is a member of the Federalist Society, a group of conservatives and libertarian lawyers and legal students interested in conservative legal theory.[35]

As a visiting professor at Duke University School of Law, Alito taught Current Issues in Constitutional Interpretation in fall 2011 and a course in the Master of Laws in Judicial Studies program in summer 2012.[36]

Court of Appeals judge

Nomination and confirmation

Third Circuit Judges Leonard I. Garth, for whom Alito clerked, and Maryanne Trump Barry, under whom Alito worked as an assistant U.S. Attorney, recommended Alito's judicial nomination to President George H. W. Bush.[21] On February 20, 1990, Bush nominated Alito to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, to a seat vacated by John Joseph Gibbons. The American Bar Association rated Alito "Well Qualified" at the time of his nomination. He was confirmed by unanimous consent in the Senate on April 27, 1990,[37][38] and received his commission three days later. As a Third Circuit judge, his chambers were in Newark, New Jersey.[18]

Notable opinions

- Abortion

- On a Third Circuit panel, the majority in Planned Parenthood v. Casey overturned one part of a law regulating abortion, the provision mandating that married women first inform their husbands if they sought an abortion. Alito, the third judge on the panel, disagreed, arguing that he would have upheld the spousal notification requirement along with the rest of the law.

- Federalism

- A dissenting opinion in United States v. Rybar, 103 F.3d 273 (3d Cir. 1996), arguing that a U.S. law banning private citizens from owning submachine guns was similar to one struck down by the Supreme Court in United States v. Lopez and thus outside the authority of Congress under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

- A majority opinion in Chittister v. Department of Community & Economic Development, 226 F.3d 223 (3d Cir. 2000). This case concerned an employee's claim of wrongful termination under the Family and Medical Leave Act against the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. States are free to maintain sovereign immunity under the U.S. Constitution. Since Pennsylvania had maintained its immunity to such suits, Alito affirmed the lower court's dismissal of the employee's claims.

- First Amendment

- A majority opinion in Saxe v. State College Area School District, 240 F.3d 200 (3d Cir. 2001), holding that a public school district's anti-harassment policy was unconstitutionally overbroad and therefore violated First Amendment guarantees of free speech.

- A majority opinion in ACLU v. Schundler, 168 F.3d 92 (3d Cir. 1999), holding that a government-sponsored holiday display consisting solely of religious symbols was impermissible, but that a mixed display including both secular and religious symbols was permissible if balanced in a generally secular context.

- A dissenting opinion in C. H. v. Oliva (3d Cir. 2000), arguing that the removal and subsequent replacement in "a less conspicuous spot" of a kindergartener's religious themed poster was, at least potentially, a violation of his right to free expression.

- Fourth and Eighth Amendments

- A dissenting opinion in Doe v. Groody, arguing that qualified immunity should have protected police officers from a finding of having violated constitutional rights when they strip-searched a mother and her ten-year-old daughter while carrying out a search warrant that authorized the search of a residence.

- A unanimous opinion in Chadwick v. Janecka (3d Cir. 2002), holding that there was "no federal constitutional bar" to the "indefinite confinement" of a man imprisoned for civil contempt because he would not pay his $2.5 million debt to his wife.

- Civil rights

- A majority opinion in Williams v. Price, 343 F.3d 223 (3d Cir. 2003), granting a writ of habeas corpus to a black state prisoner after state courts had refused to consider the testimony of a witness who stated that a juror had uttered derogatory remarks about blacks during an encounter in the courthouse after the conclusion of the trial.[39]

- A dissenting opinion in Glass v. Philadelphia Electric Company, 34 F.3d 188 (3rd Cir. 1994), arguing that a lower court did not abuse its discretion in excluding certain evidence of past conduct that defendant had created a hostile and racist work environment.

- A majority opinion in Robinson v. City of Pittsburgh, 120 F.3d 1286 (3rd Cir. 1997), rejecting a female police officer's Equal Protection-based sexual harassment and retaliation claims against the city and certain police officials and rejecting her Title VII-based retaliation claim against the city, but allowing her Title VII-based sexual harassment claim against the city.

Nomination to U.S. Supreme Court

On July 1, 2005, Associate Justice Sandra Day O'Connor announced her retirement from the Supreme Court effective upon the confirmation of a successor. President George W. Bush first nominated John G. Roberts to the vacancy, but when Chief Justice William Rehnquist died on September 3, Bush withdrew Roberts's nomination to fill O'Connor's seat and instead nominated Roberts to the Chief Justiceship. On October 3, Bush nominated Harriet Miers to replace O'Connor. Miers withdrew her acceptance of the nomination on October 27 after encountering widespread opposition.

On October 31, Bush announced that he was nominating Alito to O'Connor's seat, and he submitted the nomination to the Senate on November 10.[40] Alito was unanimously rated "well qualified" to fill the Associate Justice post by the American Bar Association's Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary, which measures the professional qualifications of a nominee.[41] The committee rates judges as "not qualified", "qualified", or "well qualified".[42] Leonard Leo was selected to play a role in shepherding Alito's appointment through the Senate.[43]

Alito's confirmation hearing was held from January 9 to 13, 2006. Two active-duty members of the Third Circuit, Judge Maryanne Trump Barry and Chief Judge Anthony J. Scirica, testified in Alito's confirmation hearing, as did five senior and retired circuit judges.[44] Alito responded to some 700 questions over 18 hours of testimony. He rejected the use of foreign legal materials in the Constitution, did not state a position on cameras in courtrooms (he had supported them while on the 3rd Circuit), said Congress could choose to outlaw LGBT employment discrimination in the United States if it wished, and told then-Senator Joe Biden (D-DE) that he endorsed a weak version of the unitary executive theory.[45]

On January 24, his nomination was voted out of the Senate Judiciary Committee on a 10–8 party line vote. Democratic Senators characterized Alito as a hard-right conservative in the mold of Clarence Thomas or Robert Bork. Alito professed reluctance to commit to any type of ideology, stating he would act as an impartial referee. He said he would look at abortion with an open mind but would not state how he would rule on Roe v. Wade if that decision were to be challenged.

Democrats on the committee asked Alito about his past association with the conservative group Concerned Alumni of Princeton.[46] Alito said that he had listed an affiliation with the group on his application to Ronald Reagan's Justice Department in order to establish his conservative credentials: "You have to look at the question that I was responding to and the form that I was filling out... I was applying for a position in the Reagan administration. And my answers were truthful statements, but what I was trying to outline were the things that were relevant to obtaining a political position."[47] During the confirmation hearings, Alito disavowed the group, whose views were criticized as racist and sexist, saying: "I disavow them. I deplore them. They represent things that I have always stood against and I can't express too strongly."[47] During Alito's Senate confirmation hearings, his wife, Martha Ann Alito, broke into tears after Republicans expressed their disapproval of how some Democrats on the panel were characterizing Alito.[48]

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) formally opposed Alito's nomination. The ACLU has only taken this step three other times in its entire history, opposing the nominations of William Rehnquist, Robert Bork and Brett Kavanaugh.[49] In releasing its report[50] on Alito, ACLU Executive Director Anthony Romero said, "At a time when our president has claimed unprecedented authority to spy on Americans and jail terrorism suspects indefinitely, America needs a Supreme Court justice who will uphold our precious civil liberties. Alito's record shows a willingness to support government actions that abridge individual freedoms."[51]

Debate on the nomination began in the full Senate on January 25. After a failed filibuster attempt by Senator John Kerry, the Senate confirmed Alito to the Supreme Court on January 31 by a vote of 58–42,[52] with four Democratic senators, Tim Johnson, Robert Byrd, Kent Conrad and Ben Nelson, voting for confirmation and one Republican, Lincoln Chafee, and an Independent, Jim Jeffords, voting against.[53][54] Alito became the 110th justice, the second Italian-American,[55][56] and the 11th Catholic in the history of the Supreme Court, and the fifth Catholic on the Court at the time he assumed office.[57]

Because Alito joined the Court mid-term, he did not participate in the decisions of most of the early cases in the Court term because he had not heard arguments for them. These decisions were released with an 8-member Court; none were 4–4, so Alito would not have been the deciding vote in any of them if he had participated. Only three of these cases – Garcetti v. Ceballos, Hudson v. Michigan, and Kansas v. Marsh – were reargued since a tie needed to be broken.

U.S. Supreme Court

Alito delivered his first written opinion on May 1, 2006, in Holmes v. South Carolina, a case involving the right of criminal defendants to present evidence that a third party committed the crime. From the beginning of the Rehnquist Court to the nomination of Justice Elena Kagan, new justices have been given unanimous opinions to write as their first opinion, often done as a courtesy "breaking in" of new justices, so that every justice has at least one unanimous, uncontroversial opinion under their belt. Alito wrote for a unanimous court in ordering a new trial for Bobby Lee Holmes due to South Carolina's rule that barred such evidence based on the strength of the prosecution's case, rather than on the relevance and strength of the defense evidence itself. His other majority opinions in his first term were in Zedner v. United States, Woodford v. Ngo, and Arlington Central School District Board of Education v. Murphy.

In his first term, Alito voted fairly conservatively. For example, in the three reargued cases (Garcetti v. Ceballos, Hudson v. Michigan and Kansas v. Marsh), Alito created a 5–4 majority by voting with the four other conservative Justices – Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas. He further voted with the conservative wing of the court on Sanchez-Llamas v. Oregon[58] and Rapanos v. United States. Alito also dissented in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, alongside Justices Scalia and Thomas.

In 2013, Alito was considered "one of the most conservative justices on the Court".[3] But while his voting record is conservative, he does not always join the most conservative Justices on the Court. On February 1, 2006, in Alito's first decision on the Supreme Court, he voted with the majority (6–3) to refuse Missouri's request to vacate the stay of execution issued by the Eighth Circuit for death-row inmate Michael Taylor; Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Scalia and Thomas were in favor of vacating the stay. Missouri had twice asked the justices to lift the stay and permit the execution.[59]

Moreover, despite having been at one time nicknamed "Scalito", Alito's views have differed from those of Scalia (and Thomas), as in the Michael Taylor case cited above and various other cases of the 2005 term. A fierce critic of reliance on legislative history in statutory interpretation, Scalia was the only member of the Court in Zedner v. United States not to join a section of Alito's opinion that discussed the legislative history of the statute in question. In two higher-profile cases, involving the constitutionality of political gerrymandering and campaign finance reform (LULAC v. Perry and Randall v. Sorrell), Alito adopted narrow positions, declining to join the bolder positions advanced by either philosophical side of the Court. According to a scotusblog.com analysis of 2005 term decisions, Alito and Scalia concurred in the result of 86% of decisions (in which both participated), and concurred in full in 75%.[60]

Alito's majority opinion in the 2008 worker protection case Gomez-Perez v. Potter cleared the way for federal workers who experience retaliation after filing age discrimination complaints to sue for damages. He sided with the liberal bloc of the court, inferring protection against retaliation in the federal-sector provision of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act despite the lack of an explicit provision concerning retaliation.

In 2020, Alito wrote a dissent joined by Clarence Thomas to Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, arguing that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 does not prohibit discrimination by sexual orientation or gender identity and criticizing the majority's interpretation of Title VII.[61][62] In October 2020, Alito agreed with the other justices to deny an appeal filed by Kim Davis, a county clerk who refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, but joined Thomas in writing a separate opinion reiterating his dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges and expressing his belief that the ruling was wrongly decided.[63][64][65]

On November 12, 2020, Alito made headlines for comments about the COVID-19 pandemic. Speaking to the Federalist Society, Alito criticized what he called the "loss of individual liberties", saying, "We have never before seen restrictions as severe, extensive and prolonged as those experienced for most of 2020", and called the pandemic "a Constitutional stress test".[66]

Abortion

In 2003, Congress passed the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, which led to a lawsuit in the case of Gonzales v. Carhart. The Court had previously ruled in Stenberg v. Carhart that a state's ban on partial birth abortion was unconstitutional because such a ban did not have an exception in the case of a threat to the health of the mother. The membership of the Court changed after Stenberg, with Roberts and Alito replacing Rehnquist (a dissenter in Roe) and O'Connor (a supporter of Roe) respectively. Further, the ban at issue in Gonzales v. Carhart was a federal statute, rather than a state statute as in the Stenberg case.

On April 18, 2007, the Supreme Court handed down a decision ruling the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act constitutional. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the five-justice majority that Congress was within its power to generally ban the procedure, although the Court left open the door for as-applied challenges. Kennedy said that the challenged statute was consistent with the Court's prior decisions in Roe v. Wade, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and Stenberg v. Carhart, without saying whether they were valid.

Alito joined fully in the majority, as did Roberts. Thomas filed a concurring opinion, joined by Scalia, contending that the Court's prior decisions in Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey should be reversed, and also noting that the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act may exceed the powers of Congress under the Commerce Clause. Alito, Roberts, and Kennedy did not join that assertion. Justices Ginsburg, Souter, Breyer, and Stevens dissented, contending that the ruling ignored Supreme Court abortion precedent.

On May 2, 2022, Politico published a leak of a first draft of a majority opinion by Alito that circulated among the justices in February 2022 for the upcoming decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. The opinion would overturn Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, and would likely either severely restrict access to abortion or make it completely illegal in states with trigger laws.[67]

Free speech

Alito has also dissented from the Supreme Court's conservative justices on free speech cases, one of which, Snyder v. Phelps, had to do with Westboro Baptist Church members' right to protest a military funeral.[68] Alito offered the sole dissenting opinion, saying protesters "were sued under a very well-established tort that goes back to the 19th century, the intentional infliction of emotional, of severe emotional distress. And I thought that this tort constituted a reasonable exception to the First Amendment, but my colleagues disagreed about that."[69]

In the 2007 landmark free speech case Morse v. Frederick, Alito joined Roberts's majority decision that speech advocating drug use can be banned in public schools, but also warned that the ruling must be circumscribed so as not to interfere with political speech, such as discussion of the medical marijuana debate.

Personal life

Since 1985, Alito has been married to Martha-Ann Alito (née Bomgardner), once a law librarian, who met Alito during his many trips to the library as a law clerk;[18] she has family roots in Oklahoma. They have two grown children, Philip and Laura. Alito resided with his family in West Caldwell, New Jersey before his Supreme Court nomination.[70] Alito socialized with Judge Edward R. Becker and his classmate, Senate Judiciary Chairman Arlen Specter.[21] Alito has since moved to Washington, D.C.

After graduating from Princeton, Alito was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Signal Corps and assigned to the United States Army Reserve. At Yale, he was a classmate of future dean Anthony T. Kronman and one year behind future Justice Clarence Thomas.[15] After graduating from Yale Law School, Alito served on active duty from September to December 1975. The remainder of his time in the Army was served in the inactive Reserves. He was a captain when he received an honorable discharge in 1980.[16]

In 2013, as part of the ongoing fallout from the Edward Snowden case, it was revealed by former National Security Agency analyst Russell Tice that during 2002 and 2003 Alito's phones, as well as his staff and his family, were targeted for surveillance by the National Security Agency.[71][72]

Alito is an avid baseball fan and a longtime fan of the Philadelphia Phillies.[73] He delivered the Supreme Court Historical Society's 2008 Annual Lecture "The Origin of the Baseball Antitrust Exemption", which was also published in two journals.[74][75]

Bibliography

- Foreword, 1 SETON HALL CIR. REV. 1 (2005).

- Panel Speaker at the Federalist Society's 2000 National Lawyers Convention: Presidential Oversight and the Administrative State, in 2 ENGAGE (Federalist Soc'y, Wash. D.C.) 11 (2001).

- The Role of the Lawyer in the Criminal Justice System, 2 FEDERALIST SOC'Y CRIM. L. NEWS (Federalist Soc'y, Wash., D.C.) 3 (1998)

- Change in Continuity at the Office of Legal Counsel, 15 CARDOZO L. REV. 507 (1993).

- Reviewing the Sentencing Commission's 1991 Annual Report, 5 FED. SENT. REP. 166 (1992).

- The First Amendment: Information, Publication and the Media, 1 SETON HALL CONST. L.J. 327 (1991).

- What Role Should Individual Sentencing Judges Play in the Guideline Development Process?, 1 FED SENT. REP. 372 (1989).

- Racketeering Made Simple(r), in THE RICO RACKET 1 (Gary L. McDowell ed. 1989).

- Introduction to After the Independent Counsel Decision: Is Separation of Powers Dead?, 26 AM. CRIM. L. REV. 1667 (1989).

- Shift Won't Hamper Crime Fight, DAILY J. (Vineland, N.J.), May 5, 1989.

- The Year Wasn't So Bad, NAT'L. L.J., Sep. 26, 1998, at 12.

- Documents and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination, 48 U. PITT. L. REV. 27 (1986).

- Equal Protection and Classification Based on Family Membership, 80 DICK. L. REV. 410 (1976).

- "The "Released Time" Cases Revisited: A Study of Group Decisionmaking by the Supreme Court". 83 YALE L.J. 1202. 1974. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015.

- An Introduction to the Italian Constitutional Court (A.B. Thesis, Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson School Scholar Project, May 31, 1972).

Related documents

- Legal Memo written while working in the United States Solicitor General's office regarding the Fleeing felon rule. (May 18, 1984) (PDF)

- 'Personal Qualifications Statement' when applying to be an Assistant Attorney General under Pres. Ronald Reagan. (November 15, 1985)

- Legal Memo written as Deputy Asst. Attorney General to the OMB’s General Counsel regarding OMB authority of FDIC funds. (1986) (PDF)

- House Committee on the Judiciary testimony regarding unpublished court opinions. (1990) (PDF)

- 2003 Financial Disclosure

- 2004 Financial Disclosure

- Response to a Senate Judiciary Committee questionnaire (November 30, 2005) (PDF), (Appendix1 Appendix2 Appendix3 Appendix4)

See also

References

- ^ Register of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Courts (54th ed.). U.S. Government Printing Office Washington: 1988. 1988. p. 92. Archived from the original on February 24, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Babington, Charles (February 1, 2006). "Alito Is Sworn In On High Court: Senators Confirm Conservative Judge Largely on Party Lines". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 25, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Granick, Jennifer and Sprigman, Christopher (June 27, 2013) "The Criminal N.S.A." Archived July 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ "Sam Alito: A Civil Man". The American Spectator. April 21, 2014. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^ "Alito called 'perfect' student". The Washington Times. December 13, 2005. Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ Russakoff, Dale; Becker, Jo (January 8, 2006). "A Search for Order, an Answer in the Law". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 19, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Justice Samuel A. Alito. The Italian Side of the Story". i-Italy. 2017. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- ^ Times of Trenton Staff Writers (February 12, 2013). "Rose Alito, mother of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito Jr., is mourned during funeral in Hamilton". The Times of Trenton. Trenton, New Jersey. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Barone, Michael. "It's inspiring to see Alito's background come to foreground: Alito" Archived March 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Sun-Times, January 18, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2007. "In his opening statement to the Judiciary Committee, Judge Samuel Alito told the senators where he comes from. First, Hamilton Township, N.J., the modest-income suburb of Trenton, where he grew up."

- ^ Samuel A. Alito Jr. biography Archived April 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, FindLaw. Retrieved November 20, 2006.

- ^ Alito, Samuel. "An Introduction to the Italian Constitutional Court". Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020 – via catalog.princeton.edu.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Report of the Chairman − Samuel Alito Archived November 26, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Conference on the Boundaries of Privacy in American Society, Woodrow Wilson Sch. of Pub. & Int'l Affairs, Princeton Univ. at 5 (January 4, 1972).

- ^ Daily Princetonian Archived September 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Nominee chaired conference recommending protection of privacy, gay rights (October 2005).

- ^ "The Princetonian". Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Neil A.; Shane, Scott (November 1, 2005). "Alito Is Seen as a Methodical Jurist With a Clear Record". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e The washington Post (November 3, 2005) "Alito Joined ROTC While at Princeton" Archived December 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Mark F. (2006)."A Tiger on the Court: Sam Alito ’72 at Princeton," Archived June 15, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Princeton Alumni Weekly, March 8. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Jan Crawford Greenburg (2007). Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court. Penguin Group. ISBN 9781594201011. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ "Alito has a record of steady conservatism, reputation for civility Archived February 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine", Chicago Tribune, October 31, 2005.

- ^ "C-SPAN Supreme Court Week – Justices In Their Own Words – Interview With Associate Justice Samuel Alito". Supremecourt.c-span.org. January 31, 2006. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick, David D. (November 8, 2005). "Interlocking Friendships Connect a Chairman and a Nominee". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Las Vegas Sun Archived June 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, October 31, 2005

- ^ "Samuel A. Alito, Jr". Oyez Project. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (December 1, 2005). "Alito File Shows Strategy to Curb Abortion Ruling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (November 20, 2005). "Before Supreme Court, Alito Had Winning Record". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (November 29, 2005). "Alito Memos Supported Expanding Police Powers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Washington Times Archived November 14, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, November 14, 2005

- ^ Rangel, Jesus (August 27, 1988). "ALL 20 ACQUITTED IN JERSEY MOB CASE". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Wakin, Daniel J. (November 2, 2005). "A Prosecutor Known for His Common Sense and Straightforward Style". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Verhovek, Sam Howe (March 22, 1988). "Bogus Threats Suspected in Indian Case". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Schwartz, Ethan (March 11, 1989). "EX-PROSECUTOR FOUND INSANE IN CASE OF FAKED THREATS". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ Hanley, Robert (February 4, 1989). "U.S. Links Man With 3 Bombs To a Terror Plot". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ "The Justices of the United States Supreme Court". Supreme Court Review. Archived from the original on April 25, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ Alito speaks to Seton Hall grads Archived November 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine USA Today. May 27, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ Judicial Society Lauds Alito Nomination Archived November 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Fox News. 2 November 2005.

- ^ "Associate Justice Samuel A. Alito". Duke University School of Law. Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ "PN1077 — Samuel A. Alito Jr. — The Judiciary". Congress.gov. April 27, 1990. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ "Alito Sworn In As High Court Justice". CBS News. February 11, 2009. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2006. Retrieved October 31, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ New York Times (October 31, 2005) "Bush Picks Appeals Court Judge to Succeed O'Connor on Court" Archived January 21, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Statement of Stephen L. Tober, Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary American Bar Association, concerning the Nomination of the Honorable Samuel A. Alito, Jr. (January 12, 2006)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ USA Today ( January 4, 2006)"Alito gets 'well-qualified' rating from American Bar Association" Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Toobin, Jeffrey. "The Conservative Pipeline to the Supreme Court". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (2006). "7 Federal Appeals Judges to Testify to Alito's Character". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (2006). "Few Glimmers of How Conservative Judge Alito Is". The New York Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ "Dems Slam Alito's Alumni Group". Fox News Channel. January 12, 2006. Archived from the original on September 4, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ a b Stefanski, Mark (January 13, 2006). "Alito disavows conservative alumni group". Daily Princetonian. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Marlantes, Liz (January 11, 2005). "Alito Grilling Gets Too Intense for Some". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- ^ Robert Bork and John Roberts Archived June 30, 2007, at archive.today

- ^ "Report of the American Civil Liberties Union on the Nomination of Third Circuit Court Judge Samuel A. Alito Jr., to be Associate Justice on the United States Supreme Court" (PDF). American Civil Liberties Union. December 9, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ "ACLU Opposes Nomination of Judge Alito". American Civil Liberties Union. January 9, 2006. Archived from the original on January 12, 2006.

- ^ "Alito Confirmed as Newest Supreme Court Justice". NPR. January 31, 2006. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ Roll Call Vote 109th Congress - 2nd Session (on the confirmation of Samuel Alito of New Jersey) Archived March 21, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, United States Senate, January 31, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (February 1, 2006). "Alito Sworn In as Justice After Senate Gives Approval". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ Hurt, Charles (February 1, 2006). "Alito sworn in as 110th justice". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ^ "Alito sworn in as nation's 110th Supreme Court justice (CNN.com)". Archived from the original on February 4, 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2006.

- ^ Religious affiliation of Supreme Court justices Note: Justice Sherman Minton converted to Catholicism after he retired.

- ^ "Sanchez-Llamas v. Oregon, 04-10566" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ "Justice Alito casts his first vote" Archived October 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine February 2, 2006. CNN.

- ^ SCOTUS Blog Archived September 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (By scotusblog.com's reckoning, this is less agreement than between Scalia and Kennedy, O'Connor and Souter, or Stevens and Ginsburg.) On the recent abortion ruling, Alito simply joined Anthony Kennedy's opinion rather than join Scalia in Thomas's stronger assertion.

- ^ Neidig, Harper (June 15, 2020). "Workers can't be fired for being gay or transgender, Supreme Court rules". The Hill. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Gerstein, Josh; Rainey, Rebecca (June 15, 2020). "Supreme Court finds federal law bars LGBT discrimination in workplace". Politico. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ Ariane de Vogue; Chandelis Duster. "Justices Thomas and Alito lash out at the decision that cleared way for same-sex marriage". CNN. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ Kyle Balluck (October 5, 2020). "Supreme Court rejects bid by ex-Kentucky clerk who defied gay marriage ruling to block lawsuit". TheHill. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ "Supreme Court rejects appeal from county clerk who wouldn't issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ Barnes, Robert. "Justice Alito says pandemic has resulted in 'unimaginable' restrictions on individual liberty". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 19, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ Gerstein, Josh; Ward, Alexander (May 2, 2022). "Supreme Court has voted to overturn abortion rights, draft opinion shows". Politico. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ "Facts and Case Summary - Snyder v. Phelps". Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ "Samuel Alito on Conversations with Bill Kristol". Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Alito's Supreme Court Nomination Confirmed Archived October 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, NPR. Retrieved September 20, 2007. "Alito and his wife, Martha-Ann Bomgardner, live in West Caldwell, N.J. His sister Rosemary Alito is a labor attorney. "

- ^ ""I held in my hand Judge Alito's targeting information for his phones and his staff and his family."". PBS. August 2013. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ youtu.be/d6m1XbWOfVk?t=3m1s NSA Blackmailing Obama? | Interview with Whistleblower Russ Tice, Breaking the Set, Abby Martin, Published July 9, 2013, excerpt: "I held Judge Alito's paperwork in my hand"

- ^ "Samuel Alito on Conversations with Bill Kristol". Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ^ Alito, Samuel A. Jr. (June 15, 2009). "The Origin of the Baseball Antitrust Exemption: Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs". Journal of Supreme Court History. 34 (2): 183–195. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5818.2009.01208.x. S2CID 247668532.

- ^ Alito, Samuel A. Jr. (2009). "The Origin of the Baseball Antitrust Exemption". Baseball Research Journal. 38 (2). Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

Further reading

- Bazelon, Emily (October 31, 2005). "Alito v. O'Connor". Slate.

- "Bush choice sets up court battle". BBC.

- Collins, Ronald K.L. (October 31, 2005). Judge Alito: fairly strong on free expression.

- Collins, Ronald K.L. (November 3, 2005). Alito as government lawyer: '84 broadcast-regulation case.

- Davis, Elliott M. (Summer 2007). The Newer Textualism: Justice Alito's Statutory Interpretation. Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy

- Dickerson, John (October 31, 2005). "Ready To Rumble". Slate.

- Federal Judicial Center. Judges of the United States Archived January 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (official curriculum vitae).

- Gibson, James L. and Gregory A. Caldeira, "Confirmation politics and the legitimacy of the US Supreme Court: Institutional loyalty, positivity bias, and the Alito nomination." American Journal of Political Science 53.1 (2009): 139-155 online.

- Hook, Janet (November 1, 2005). "Bush's Supreme Court Nominee: A Phillies Fan With Blue-Chip Legal Stats." Los Angeles Times. P. A1.

External links

- Samuel A. Alito Jr. at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Samuel Alito at Ballotpedia

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Appearances at the U.S. Supreme Court from the Oyez Project

- The Nomination of Samuel A. Alito at the Law Library of Congress

- Fox, John, Capitalism and Conflict, Biographies of the Robes, Samuel Anthony Alito, Jr. Public Broadcasting Service.

- Washington Post Profile

- Daily Princetonian profile

- Issue positions and quotes at OnTheIssues

- Profile at SourceWatch

- "The Record of Samuel Alito: A Preliminary Review". People For the American Way. 2005.

- Read Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding Alito

- Alito at Jurist.org

- National Archives Alito links

- The White House Judicial Nominations page on Alito

- Supreme Court Justice Nomination Hearings on Samuel Anthony Alito, Jr. in January 2006 United States Government Publishing Office

About the page

Presented content of the Wikipedia article was extracted in 2022-05-13 based on https://en.wikipedia.org/?curid=1199173