Robert Maxwell

Robert Maxwell | |

|---|---|

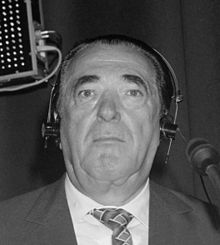

Maxwell at the Global Economic Panel in Amsterdam (1989) | |

| Member of Parliament for Buckingham | |

| In office 15 October 1964 – 29 May 1970 | |

| Preceded by | Frank Markham |

| Succeeded by | William Benyon |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ján Ludvík Hyman Binyamin Hoch 10 June 1923 Slatinské Doly, Czechoslovakia (now Solotvyno, Ukraine) |

| Died | 5 November 1991 (aged 68) Sea around the Canary Islands, Spain |

| Resting place | Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery, Jerusalem |

| Citizenship | Czechoslovak British (since 1946) |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 9, including Christine, Isabel, Ian, Kevin and Ghislaine |

| Occupation | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1940–1945 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Military Cross |

Ian Robert Maxwell MC (born Ján Ludvík Hyman Binyamin Hoch; 10 June 1923 – 5 November 1991) was a British media proprietor, Member of Parliament (MP), suspected spy, and fraudster.[1] Originally from Czechoslovakia, Maxwell rose from poverty to build an extensive publishing empire. After his death, huge discrepancies in his companies' finances were revealed, including his fraudulent misappropriation of the Mirror Group pension fund.[2]

Early in his life, Maxwell, an Orthodox Jew, escaped from Nazi occupation, joined the Czechoslovak Army in exile during World War II and was decorated after active service in the British Army. In subsequent years he worked in publishing, building up Pergamon Press to a major publishing house. After six years as a Labour MP during the 1960s, Maxwell again put all his energy into business, successively buying the British Printing Corporation, Mirror Group Newspapers and Macmillan Publishers, among other publishing companies.

Maxwell had a flamboyant lifestyle, living in Headington Hill Hall in Oxford, from which he often flew in his helicopter, or his luxury yacht, the Lady Ghislaine. He was litigious and often embroiled in controversy. In 1989, Maxwell had to sell successful businesses, including Pergamon Press, to cover some of his debts. In 1991, his body was discovered floating in the Atlantic Ocean, having apparently fallen overboard from his yacht. He was buried in Jerusalem.

Maxwell's death triggered the collapse of his publishing empire as banks called in loans. His sons briefly attempted to keep the business together, but failed as the news emerged that the elder Maxwell had stolen hundreds of millions of pounds from his own companies' pension funds. The Maxwell companies applied for bankruptcy protection in 1992.

Early life

Robert Maxwell was born into a poor Yiddish-speaking Orthodox Jewish family in the small town of Slatinské Doly, in the region of Carpathian Ruthenia, Czechoslovakia (now Solotvyno, Ukraine).[3][4][5] His parents were Mechel Hoch and Hannah Slomowitz. He had six siblings. In 1939, the area was reclaimed by Hungary. Most members of Maxwell's family died in Auschwitz after Hungary was occupied in 1944 by Nazi Germany, but he had years earlier escaped to France.[3] In May 1940, he joined the Czechoslovak Army in exile in Marseille.[6]

After the fall of France and the British retreat to Britain, Maxwell (using the name "Ivan du Maurier",[7] or "Leslie du Maurier",[8] the surname taken from the name of a popular cigarette brand) took part in a protest against the leadership of the Czechoslovak Army, and with 500 other soldiers he was transferred to the Pioneer Corps and later to the North Staffordshire Regiment in 1943. He was then involved in action across Europe, from the Normandy beaches to Berlin, and achieved the rank of sergeant.[3] Maxwell gained a commission in 1945 and was promoted to the rank of captain.

In January 1945, Maxwell's heroism in "storming a German machine-gun nest" during the war won him the Military Cross, presented by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.[9] Attached to the Foreign Office, he served in Berlin during the next two years in the press section.[5] Maxwell naturalised as a British subject on 19 June 1946[10] and changed his name by deed of change of name on 30 June 1948.[11]

In 1945, Maxwell married Elisabeth "Betty" Meynard, a French Protestant, and the couple had nine children over the next 16 years: Michael, Philip, Ann, Christine, Isabel, Karine, Ian, Kevin and Ghislaine.[12] In a 1995 interview, Elisabeth talked of how they were recreating his childhood family who were killed in the Holocaust.[13] Five of his children – Christine, Isabel, Ian, Kevin and Ghislaine – were later employed within his companies. His daughter Karine died of leukaemia at age three, while Michael was severely injured in a car crash in 1961, at the age of 15, when his driver fell asleep at the wheel. Michael never regained consciousness and died seven years later.[14][15][16][17]

After the war, Maxwell used contacts in the Allied occupation authorities to go into business, becoming the British and US distributor for Springer Verlag, a publisher of scientific books. In 1951, he bought three-quarters of Butterworth-Springer, a minor publisher; the remaining quarter was held by the experienced scientific editor Paul Rosbaud.[18] They changed the name of the company to Pergamon Press and rapidly built it into a major publishing house.

In 1964, representing the Labour Party, Maxwell was elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for Buckingham and re-elected in 1966. He gave an interview to The Times in 1968, in which he said the House of Commons provided him with a problem. "I can't get on with men", he commented. "I tried having male assistants at first. But it didn't work. They tend to be too independent. Men like to have individuality. Women can become an extension of the boss."[19] Maxwell lost his seat in 1970 to Conservative challenger William Benyon. He contested Buckingham again in both 1974 general elections, but without success.

At the beginning of 1969, it emerged that Maxwell's attempt to buy the tabloid newspaper News of the World had failed.[20] The Carr family, which owned the title, was incensed at the thought of a Czechoslovak immigrant with socialist politics gaining ownership, and the board voted against Maxwell's bid without any dissent. The News of the World's editor, Stafford Somerfield, opposed Maxwell's bid in an October 1968 front page opinion piece, in which he referred to Maxwell's Czechoslovak origins and used his birth name.[21] He wrote, "This is a British paper, run by British people ... as British as roast beef and Yorkshire pudding ... Let us keep it that way".[22] The paper was later purchased by Australian tycoon Rupert Murdoch, who later that year acquired The Sun, which had also previously interested Maxwell.[23]

Pergamon lost and regained

In 1969, Saul Steinberg, head of "Leasco Data Processing Corporation", was interested in a strategic acquisition of Pergamon Press. Steinberg claimed that during negotiations, Maxwell falsely stated that a subsidiary responsible for publishing encyclopedias was extremely profitable.[24][25] At the same time, Pergamon had been forced to reduce its profit forecasts for 1969 from £2.5 million to £2.05 million during the period of negotiations, and dealing in Pergamon shares was suspended on the London stock markets.[25]

Maxwell subsequently lost control of Pergamon and was expelled from the board in October 1969, along with three other directors in sympathy with him, by the majority owners of the company's shares.[26] Steinberg purchased Pergamon. An inquiry by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) under the Takeover Code of the time reported was conducted by Rondle Owen Charles Stable and Sir Ronald Leach in mid-1971.[27][5] The report concluded: "We regret having to conclude that, notwithstanding Mr Maxwell's acknowledged abilities and energy, he is not in our opinion a person who can be relied on to exercise proper stewardship of a publicly quoted company."[28][29] It was found that Maxwell had contrived to maximise Pergamon's share price through transactions between his private family companies.[24]

At the same time, the United States Congress was investigating Leasco's takeover practices. Judge Thayne Forbes in September 1971 was critical of the inquiry: "They had moved from an inquisitorial role to accusatory one and virtually committed the business murder of Mr. Maxwell." He further continued that the trial judge would probably find that the inspectors had acted "contrary to the rules of natural justice".[30] The company performed poorly under Steinberg; Maxwell reacquired Pergamon in 1974 after borrowing funds.[31]

Maxwell established the Maxwell Foundation in Liechtenstein in 1970. He acquired the British Printing Corporation (BPC) in 1981 and changed its name first to the British Printing and Communication Corporation (BPCC) and then to the Maxwell Communications Corporation (MCC). The company was later sold in a management buyout and is now known as Polestar.

Later business activities

In July 1984, Maxwell acquired Mirror Group Newspapers, the publisher of six British newspapers, including the Daily Mirror, from Reed International plc.[32] for £113 million.[33] This led to the famous media war between Maxwell and Murdoch, the proprietor of the News of the World and The Sun.

Mirror Group Newspapers (formerly Trinity Mirror, now part of Reach plc), published the Daily Mirror, a pro-Labour tabloid; Sunday Mirror; Sunday People; Scottish Sunday Mail and Scottish Daily Record. At a press conference to publicise his acquisition, Maxwell said his editors would be "free to produce the news without interference".[32] Meanwhile, at a meeting of Maxwell's new employees, Mirror journalist Joe Haines asserted that he was able to prove that their boss "is a crook and a liar".[34][35] Haines quickly came under Maxwell's influence and later wrote his authorised biography.[34]

In June 1985 Maxwell announced a takeover of Clive Sinclair's ailing home computer company, Sinclair Research, through Hollis Brothers, a Pergamon subsidiary.[36] The deal was aborted in August 1985.[37] In 1987 Maxwell purchased part of IPC Media to create Fleetway Publications. The same year he launched the London Daily News in February after a delay caused by production problems, but the paper closed in July after sustaining significant losses contemporary estimates put at £25 million.[38] At first intended to be a rival to the Evening Standard, Maxwell had made a rash decision for it to be the first 24-hour paper as well.[39]

By 1988 Maxwell's various companies owned, in addition to the Mirror titles and Pergamon Press, Nimbus Records, Maxwell Directories, Prentice Hall Information Services and the Berlitz language schools. He also owned a half-share of MTV in Europe and other European television interests, Maxwell Cable TV and Maxwell Entertainment.[31] Maxwell purchased Macmillan Publishers, the American firm, for $2.6 billion in 1988. In the same year, he launched an ambitious new project, a transnational newspaper called The European. In 1991 Maxwell was forced to sell Pergamon and Maxwell Directories to Elsevier for £440 million to cover his debts;[31] he used some of this money to buy an ailing tabloid, the New York Daily News. The same year Maxwell sold 49 percent of the stock of Mirror Group Newspapers to the public.[5]

Maxwell's links with Eastern European totalitarian regimes resulted in several biographies (generally considered to be hagiographies)[40] of those countries' leaders, with interviews conducted by Maxwell, for which he received much derision.[5] At the beginning of an interview with Romania's Nicolae Ceaușescu, then the country's communist leader, he asked, "How do you account for your enormous popularity with the Romanian people?"[41]

Maxwell was also the chairman of Oxford United, saving them from bankruptcy and attempting to merge them with Reading in 1983 to form a club he wished to call "Thames Valley Royals". He took Oxford into the top flight of English football in 1985 and the team won the League Cup a year later. Maxwell bought into Derby County in 1987. He also attempted to buy Manchester United in 1984, but refused owner Martin Edwards's asking price.

Maxwell was known to be litigious against those who would speak or write against him. The satirical magazine Private Eye lampooned him as "Cap'n Bob" and the "bouncing Czech",[43] the latter nickname having originally been devised by Prime Minister Harold Wilson[44] (under whom Maxwell was an MP). Maxwell took out several libel actions against Private Eye, one resulting in the magazine losing an estimated £225,000 and Maxwell using his commercial power to hit back with a one-off spoof magazine Not Private Eye.[45]

Israeli controversy

1948 war

A hint of Maxwell's service to Israel was provided by John Loftus and Mark Aarons, who described Maxwell's contacts with Czechoslovak communist leaders in 1948 as crucial to the Czechoslovak decision to arm Israel in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Czechoslovak military assistance was both unique and crucial for the fledgling state as it battled for its existence. According to Loftus and Aarons, it was Maxwell's covert help in smuggling aircraft parts into Israel that led to the country having air superiority during their 1948 war of independence.[46]

Mossad allegations; Vanunu case

The Foreign Office suspected that Maxwell was a secret agent of a foreign government, possibly a double agent or a triple agent, and "a thoroughly bad character and almost certainly financed by Russia". He had known links to the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), to the Soviet KGB, and to the Israeli intelligence service Mossad.[47] Six serving and former heads of Israeli intelligence services attended Maxwell's funeral in Israel, while Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir eulogised him and stated: "He has done more for Israel than can today be told."[48]

Shortly before Maxwell's death, a former employee of Israel's Military Intelligence Directorate, Ari Ben-Menashe, approached a number of news organisations in Britain and the US with the allegation that Maxwell and the Daily Mirror's foreign editor, Nicholas Davies, were both long-time agents for Mossad. Ben-Menashe also claimed that, in 1986, Maxwell informed the Israeli Embassy in London that Mordechai Vanunu revealed information about Israel's nuclear capability to The Sunday Times, then to the Daily Mirror. Vanunu was subsequently kidnapped by Mossad and smuggled to Israel, convicted of treason and imprisoned for eighteen years.[49]

Ben-Menashe's story was ignored at first, but eventually journalist Seymour Hersh of The New Yorker repeated some of the allegations during a press conference in London held to publicise The Samson Option, Hersh's book about Israel's nuclear weapons.[50] On 21 October 1991, Labour MP George Galloway and Conservative MP Rupert Allason (also known as espionage author Nigel West) agreed to raise the issue in the House of Commons under parliamentary privilege protection,[a] which in turn allowed British newspapers to report events without fear of libel suits. Maxwell called the claims "ludicrous, a total invention" and sacked Davies.[51] A year later, in Galloway's libel settlement against Mirror Group Newspapers (in which he received "substantial" damages), Galloway's counsel announced that the MP accepted that the group's staff had not been involved in Vanunu's abduction. Galloway referred to Maxwell as "one of the worst criminals of the century".[52]

Death

On 4 November 1991, Maxwell had an argumentative phone call with his son Kevin over a meeting scheduled with the Bank of England on Maxwell's default on £50,000,000 in loans. Maxwell missed the meeting, instead travelling to his yacht, the Lady Ghislaine, in the Canary Islands, Spain.[9]

On 5 November, Maxwell was last in contact with the crew of Lady Ghislaine at 4:25 a.m. local time, but was found to be missing later in the morning.[51] It has been speculated that Maxwell was urinating into the ocean nude at the time, as he often did.[9] He was presumed to have fallen overboard from the vessel, which was cruising off the Canary Islands, southwest Spain.[51][53] Maxwell's naked body was recovered from the Atlantic Ocean and taken to Las Palmas.[49] Besides a "graze to his left shoulder", there were no noticeable wounds on Maxwell's body.[9] The official ruling at an inquest held in December 1991 was death by a heart attack combined with accidental drowning,[54] although three pathologists had been unable to agree on the cause of his death at the inquest;[49] he had been found to have been suffering from serious heart and lung conditions.[55] Murder was ruled out by the judge and, in effect, so was suicide.[54] His son discounted the possibility of suicide, saying, "I think it is highly unlikely that he would have taken his own life, it wasn't in his makeup or his mentality."[9]

Maxwell was afforded a lavish funeral in Israel, attended by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, Israeli President Chaim Herzog, "no less than six serving and former heads of Israeli intelligence"[56] and many dignitaries and politicians (both government and opposition), and was buried on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.[57][58][59] Herzog delivered the eulogy and the Kaddish was recited by his fellow Holocaust survivor, friend and longtime attorney Samuel Pisar.[60]

British Prime Minister John Major said Maxwell had given him "valuable insights" into the situation in the Soviet Union during the attempted coup of 1991. He was a "great character", Major added. Neil Kinnock, then Labour Party leader, spoke of him as a man with "a zest for life" who "attracted controversy, envy and loyalty in great measure throughout his rumbustious life."

A production crew conducting research for Maxwell, a biographical film by the BBC, uncovered tapes stored in a suitcase owned by his former head of security, John Pole. Later in his life, Maxwell had become increasingly paranoid of his own employees and had the offices of those he suspected of disloyalty wired so he could hear their conversations. After Maxwell's death, the tapes remained in Pole's suitcase and were discovered by the researchers only in 2007.[61]

Aftermath: theft of pension funds and collapse of a publishing empire

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

Maxwell's death triggered a flood of instability for his publishing empire, with banks frantically calling in their massive loans. Despite the efforts of his sons Kevin and Ian, the Maxwell companies soon collapsed. It emerged that, without adequate prior authorisation, Maxwell had used hundreds of millions of pounds from his companies' pension funds to shore up the shares of the Mirror Group to save his companies from bankruptcy.[62] Eventually, the pension funds were replenished with money from investment banks Shearson Lehman and Goldman Sachs, as well as the British government.[63] This replenishment was limited and also supported by a surplus in the printers' fund, which was taken by the government in part payment of £100 million required to support the workers' state pensions. The rest of the £100 million was waived. Maxwell's theft of pension funds was therefore partly repaid from public funds. The result was that in general, pensioners received about half of their company pension entitlement.

The Maxwell companies filed for bankruptcy protection in 1992. Kevin Maxwell was declared bankrupt with debts of £400 million. In 1995, Kevin, Ian and two other former directors went on trial for conspiracy to defraud, but were unanimously acquitted by a twelve-person jury the following year.

Family

In November 1994, Maxwell's widow Elisabeth published her memoirs, A Mind of My Own: My Life with Robert Maxwell,[64] which sheds light on her life with him, when the publishing magnate was ranked as one of the richest people in the world.[65] Having earned her degree from Oxford University in 1981, Elisabeth devoted much of her later life to continued research on the Holocaust and worked as a proponent of Jewish-Christian dialogue. She died on 7 August 2013.[66]

In July 2020, Maxwell's youngest child, his daughter Ghislaine Maxwell, was arrested and charged in New Hampshire, US, with six federal crimes, involving minors' trade, travel and seducing to engage in criminal sexual activity, and conspiracy to entice children to engage in illegal sex acts, allegedly linked to her regular activity with a sex-trafficking ring with and for the equally arrested and charged therein Jeffrey Epstein (who had already died in jail the previous year).[67]

In popular culture

- Maxwell was used as inspiration for the villainous media baron Elliot Carver in the 1997 James Bond film Tomorrow Never Dies as well as its novelisation and video game adaptation.[68][69] At the film's conclusion, M orders a story spun disguising Carver's demise, saying that Carver is believed to have committed suicide by jumping off his yacht in the South China Sea.

- Maxwell appears in I Got It Bad and That Ain't Good, the second episode in the second series of the popular 1990s sitcom Goodnight Sweetheart. Played by Jonathan Cake, the character attempts to swindle Phoebe out of her pension money with the offer to invest it. He takes inspiration from a jar of Maxwell House coffee for his new surname, but instead comes up with "Robert House".[citation needed]

- A BBC drama, Maxwell, covering his life shortly before his death, starring David Suchet and Patricia Hodge, was aired on 4 May 2007.[70] Suchet won the International Emmy Award for Best Actor for his performance as Maxwell.[71]

- A one-person show about Maxwell's life, Lies Have Been Told, written by Rod Beacham, was performed by Phillip York at London's Trafalgar Studios in 2006.[72]

- The Fourth Estate, a 1996 novel by Jeffrey Archer, is based on the lives of Robert Maxwell and Rupert Murdoch.[73]

- Max, a novel by Juval Aviv, is based on Aviv's investigation into the death of Robert Maxwell.[74]

- Maxwell pressured Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev to cancel the contract between Elorg and Nintendo concerning the rights to the game Tetris.[75]

- In the 1992 final series of British sitcom The New Statesman, a recurring joke is Alan B'Stard's knowledge that Maxwell faked his death and is still alive. In the fourth episode, B'Stard visits war-torn Herzegovina, ostensibly to negotiate a peace treaty, but his plan all along has been to smuggle Maxwell out of the country to a luxury hideaway, in return for a handsome slice of the Mirror Group funds. It transpires, however, that Maxwell has already spent the money, and the episode ends with a vengeful B'Stard giving him 'an amazing deja-vu experience' - pushing him over the side of his yacht, where he presumably dies for real.

See also

- Daily News (Perth, Western Australia) § Later years

- Ghislaine Maxwell

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously at sea

- Maxwell Communication Corporation

- Maxwellisation

- Scottish Daily News

Notes

- ^ Parliamentary privilege allows MPs to ask questions in Parliament without risk of being sued for defamation.

References

- ^ "Robert Maxwell's sons speak out about their fraudster father". Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "A Notorious Fraud – the Robert Maxwell Farrago". Australian Guardians. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Марк Штейнберг. Евреи в войнах тысячелетий. p. 227. ISBN 5-93273-154-0 (in Russian)

- ^ Иван Мащенко (7–13 September 2002). Медиа-олигарх из Солотвина. Зеркало недели (in Russian) (#34 (409)). Archived from the original on 22 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Whitney, Craig R. (6 November 1991). "Robert Maxwell, 68: From Refugee to the Ruthless Builder of a Publishing Empire". The New York Times. p. 5.

- ^ "Ludvík Hoch (Maxwell) in the database of Central Military Archive in Prague".

- ^ Walters, Rob (8 December 2009). "Naughty Boys: Ten Rogues of Oxford". google.se. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ LLC, Sussex Publishers (May 1988). Spy. Sussex Publishers, LLC.

- ^ a b c d e Kirsch, Noah. "Long Before Ghislaine Maxwell Disappeared, Her Mogul Father Died Mysteriously". Forbes.

- ^ "No. 37658". The London Gazette. 19 July 1946. p. 3739.

- ^ "No. 38352". The London Gazette. 13 July 1948. p. 4046.

- ^ Haines, Joe (1988). Maxwell. London: Futura. pp. 434 et seq. ISBN 0-7088-4303-4.

- ^ Witchell, Alex (15 February 1995). "AT LUNCH WITH: Elisabeth Maxwell; Questions Without Answers". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Maxwell: The final verdict

- ^ A mind of my own by Elisabeth Maxwell

- ^ "Free Research Papers – Information Intelligence, 1991". free-researchpapers.com. 28 March 1999. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Rampton, James (28 April 2007). "Maxwell was a monster - but much more, too". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Haines (1988) 135

- ^ Barwick, Sandra (25 October 1994). "The beast and his beauties". The Independent.

- ^ "1969: Murdoch wins Fleet Street foothold". BBC. 2 January 1969.

- ^ Greenslade, Roy (2004) [2003]. Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits From Propaganda. London: Pan. p. 395. ISBN 9780330393768.

- ^ Grundy, Bill (24 October 1968). "Mr Maxwell and the Ailing Giant". The Spectator. p. 6.

- ^ "The Maxwell Murdoch tabloid rivalry". BBC News. 5 November 2011.

- ^ a b Dennis Barker and Christopher Sylvester "The grasshopper", – Obituary of Maxwell, The Guardian, 6 November 1991. Retrieved on 19 July 2007.

- ^ a b Nicholas Davenport "Money Wanted: A Board of Trade inquiry", The Spectator, 29 August 1969, p.24

- ^ Nicholas Davenport "Money: The End of the Affair", The Spectator, 17 October 1969, p.22

- ^ Stable, Rondle Owen Charles; Leach, Sir Ronald; Industry, Great Britain Department of Trade and (1971). Report on the Affairs of the International Learning Systems Corporation Limited: And Interim Report on the Affairs of Pergamon Press Limited, Investigation Under Section 165(b) of the Companies Act 1948. H.M. Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-510728-3.

- ^ Stable, Rondle Owen Charles; Leach, Sir Ronald; Industry, Great Britain Department of Trade and (1971). Report on the Affairs of the International Learning Systems Corporation Limited: And Interim Report on the Affairs of Pergamon Press Limited, Investigation Under Section 165(b) of the Companies Act 1948. H.M. Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0-11-510728-3.

- ^ Wearing, Robert (2005). Cases in Corporate Governance. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 1412908779.

- ^ Betty Maxwell, p. 542

- ^ a b c "Robert Maxwell: Overview", keputa.net

- ^ a b "Briton Buys the Mirror Chain", The New York Times, 14 July 1984

- ^ Roy Greenslade Press Gang: How Newspapers Make Profits From Propaganda, London: Pan, 2004 [2003], p.395

- ^ a b "Say It Ain't So, Joe", The Spectator, 22 February 1992, p.15

- ^ Roy Greenslade Press Gang, p.395

- ^ "Sinclair to Sell British Unit". The New York Times. 18 June 1985. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ "Sinclair: A Corporate History". Planet Sinclair. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ "Maxwell Closes London Paper", Glasgow Herald, 25 July 1987, p.3

- ^ Duncan Campbell "The London legacy of Cap'n Bob", The Guardian, 28 August 2006

- ^ David Ellis and Sidney Urquhart "Maxwell's Hall of Shame", Time, 8 April 1991

- ^ Editorial: "Breaking the Spell", The Spectator, 21 December 1991, p.3

- ^ "", Headington History

- ^ Jon Kelly "The strange allure of Robert Maxwell", BBC News, 4 May 2007

- ^ Reuters "Murdoch conclusion stirs memories of his old foe Maxwell", Chicago Tribune, 1 May 2012

- ^ "Not Private Eye", Tony Quinn, Magforum.com, 6 March 2007

- ^ John Loftus and Mark Aarons, The Secret War Against the Jews.

- ^ "FO Suspected Maxwell Was a Russian Agent, Papers Reveal". The Telegraph, 2 November 2003

- ^ Gordon Thomas (1999), Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad, New York: St. Martin's Press, p. 23

- ^ a b c Robert Verkaik "The Mystery of Maxwell's Death", The Independent, 10 March 2006

- ^ Hersh, Seymour M. (1991). The Samson Option : Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy (1st ed.). New York. pp. 312–15. ISBN 0-394-57006-5. OCLC 24609770.

- ^ a b c Ben Laurance and John Hooper, et al. "Maxwell's body found in sea", The Guardian, 6 November 1991

- ^ "Scottish MP wins libel damages", The Herald (Glasgow), 22 December 1992

- ^ "Robert Maxwell: A Profile". BBC News. 29 March 2001. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ a b Larry Eichel (14 December 1991). "Maxwell's Legacy Of Money Troubles Maxwell's Own Daily Mirror Newspaper Now Routinely Calls Him 'The Cheating Tycoon'". Philadelphia Inquirer

- ^ Marlise Simons (12 December 1991). "Autopsy Indicates Maxwell Did Not Drown". The New York Times.

- ^ Gordon Thomas. Gideon's Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad, page 210

- ^ Clyde Haberman (11 November 1991). "The Media Business; Maxwell Is Buried In Jerusalem", The New York Times.

- ^ "Israel gives Maxwell farewell fit for hero". The Washington Post, 11 November 1991

- ^ "George Galloway sheds light on Maxwell family and its links to Jeffrey Epstein", 23 August 2019

- ^ "Maxwell, Colossus Even in Death, Laid to Rest on Mount of Olives", jta.org, 11 November 1991

- ^ "BBC reveals secret Maxwell tapes". BBC. 25 April 2007.

- ^ Prokesch, Steven (24 June 1992). "Maxwell's Mirror Group Has $727.5 Million Loss". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Chapter 11: Major Corporate Governance Failures

- ^ Diski, Jenny (26 January 1995). "Bob and Betty". London Review of Books. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ MacIntyre, Ben (1 January 1995). "A Match for Robert Maxwell". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Roy Greenslade, "Betty, Robert Maxwell's widow, dies aged 92", The Guardian (9 August 2013)

- ^ "Ghislaine Maxwell, confidante of Jeffrey Epstein, arrested on federal charges", The Wall Street journal.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (19 December 1997). "'TOMORROW NEVER DIES': JAMES BOND ZIPS INTO THE '90S". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Turner, Kyle (30 May 2018). "There's No News Like Fake News: Tomorrow Never Dies Today". Paste Magazine. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Suchet in title role of BBC Two's Maxwell". bbc.co.uk. 16 February 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Luft, Oliver (25 November 2008). "UK scoops seven International Emmys". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ Benedict Nightingale. "Portrait of a megalomaniac." The Times, London, 13 January 2006: pg 39.

- ^ Archer, Jeffrey (1996). The Fourth Estate (First ed.). London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0002253186.

- ^ Aviv, Juval (2006). Max (First ed.). London: Random House UK. ISBN 1844138755.

- ^ Ichbiah 1997, p. 95.

Further reading

- Short BBC profile of Robert Maxwell

- Department of Trade and Industry report on Maxwell's purchase of the Mirror Group at the Wayback Machine (archived 28 October 2004)

- Biography

- Hersh, Seymour (1991). The Samson Option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy. Random House. ISBN 0-394-57006-5.

- Thomas, Gordon and Dillon, Martin. (2002). Robert Maxwell: Israel's Superspy: The Life and Murder of a Media Mogul, Carroll and Graf, ISBN 0-7867-1078-0

- Henderson, Albert, (2004) The Dash and Determination of Robert Maxwell, Champion of Dissemination, LOGOS. 15,2, pp. 65–75.

- Martin Dillon, The Assassination of Robert Maxwell, Israeli Superspy

- Joe Haines (1988) Maxwell, Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-48929-6 .

- Robert N. Miranda (2001) Robert Maxwell: Forty-four years as Publisher, in E. H. Frederiksson ed., A Century of Science Publishing, IOS Press ISBN 1-58603-148-1

- Bower Tom Maxwell the final verdict Harper Collins 1996 ISBN 0-00-638424-2

- Bower Tom Maxwell the outsider Mandarin ISBN 0-7493-0238-0

- Roy Greenslade (1992) Maxwell: The Rise and Fall of Robert Maxwell and His Empire. ISBN 1-55972-123-5

- Roy Greenslade (2011) "Pension plunderer Robert Maxwell remembered 20 years after his death". The Guardian, 3 November 2011. Accessed 20 October 2013

- Coleridge, Nicholas (March 1994). Paper Tigers: The Latest, Greatest Newspaper Tycoons. Secaucus, NJ: Birch Lane Press. ISBN 9781559722155.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Robert Maxwell

- FBI Records: The Vault - Robert Maxwell

- Opinion piece about the pension fund in the Independent in 1996

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Frank Markham |

Member of Parliament for Buckingham 1964–1970 |

Succeeded by William Benyon |

Information

About the page

Presented content of the Wikipedia article was extracted in 2021-06-13 based on https://en.wikipedia.org/?curid=5409978