Meta Platforms

Entrance to Meta's headquarters complex (pictured in 2014 as Facebook Inc.) in Menlo Park, California | |

| Meta | |

| Formerly | |

| Type | Public |

| Industry | |

| Founded | January 4, 2004 in Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide (except blocked countries) |

Key people |

|

| Brands | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owner | Mark Zuckerberg (controlling shareholder) |

Number of employees | 60,654 (March 31, 2021) |

| Divisions | Facebook Reality Labs |

| Subsidiaries | Novi Financial |

| Website | about |

| Footnotes / references [3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] | |

Meta Platforms, Inc.,[11][12] doing business as Meta[13] (formerly Facebook, Inc.[14]), is an American multinational technology conglomerate holding company based in Menlo Park, California. It is the parent organization of Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, among other subsidiaries.[15] It is one of the world's most valuable companies and is considered one of the Big Tech companies in U.S. information technology, alongside Amazon, Google (Alphabet), Apple, and Microsoft. The company generates a substantial share of its revenue from the sale of advertisement placements to marketers.[16]

Meta offers other products and services, including Facebook, Messenger, Facebook Watch, and Facebook Portal. It has also acquired Oculus, Giphy and Mapillary, and has a 9.99% stake in Jio Platforms.[17]

In October 2021, media outlets reported that the parent company of Facebook planned to change its name to "reflect its focus on building the metaverse",[18] it was rebranded as Meta later that month on October 28.[19][20] The word "meta" comes from the Greek language and means "beyond", indicating the futuristic motive.[21]

History

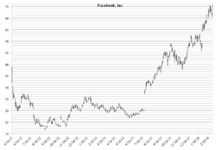

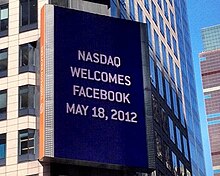

Facebook filed for an initial public offering (IPO) on January 1, 2012.[22] The preliminary prospectus stated that the company sought to raise $5 billion, had 845 million monthly active users, and a website accruing 2.7 billion likes and comments daily.[23] After the IPO, Zuckerberg would retain a 22% ownership share in Facebook and would own 57% of the voting shares.[24]

Underwriters valued the shares at $38 each, valuing the company at $104 billion, the largest valuation to date for a newly public company.[25] On May 16, one day before the IPO, Facebook announced it would sell 25% more shares than originally planned due to high demand.[26] The IPO raised $16 billion, making it the third-largest in US history (slightly ahead of AT&T Wireless and behind only General Motors and Visa). The stock price left the company with a higher market capitalization than all but a few U.S. corporations—surpassing heavyweights such as Amazon, McDonald's, Disney, and Kraft Foods—and made Zuckerberg's stock worth $19 billion.[27][28] The New York Times stated that the offering overcame questions about Facebook's difficulties in attracting advertisers to transform the company into a "must-own stock". Jimmy Lee of JPMorgan Chase described it as "the next great blue-chip".[27] Writers at TechCrunch, on the other hand, expressed skepticism, stating, "That's a big multiple to live up to, and Facebook will likely need to add bold new revenue streams to justify the mammoth valuation".[29]

Trading in the stock, which began on May 18, was delayed that day due to technical problems with the NASDAQ exchange.[30] The stock struggled to stay above the IPO price for most of the day, forcing underwriters to buy back shares to support the price.[31] At closing bell, shares were valued at $38.23,[32] only $0.23 above the IPO price and down $3.82 from the opening bell value. The opening was widely described by the financial press as a disappointment.[33] The stock nonetheless set a new record for trading volume of an IPO.[34] On May 25, 2012, the stock ended its first full week of trading at $31.91, a 16.5% decline.[35]

On May 22, 2012, regulators from Wall Street's Financial Industry Regulatory Authority announced that they had begun to investigate whether banks underwriting Facebook had improperly shared information only with select clients rather than the general public. Massachusetts Secretary of State William Galvin subpoenaed Morgan Stanley over the same issue.[36] The allegations sparked "fury" among some investors and led to the immediate filing of several lawsuits, one of them a class action suit claiming more than $2.5 billion in losses due to the IPO.[37] Bloomberg estimated that retail investors may have lost approximately $630 million on Facebook stock since its debut.[38]

Standard & Poor's added Facebook to its S&P 500 index on December 21, 2013.[39]

On May 2, 2014, Zuckerberg announced that the company would be changing its internal motto from "Move fast and break things" to "Move fast with stable infrastructure".[40][41] The earlier motto had been described as Zuckerberg's "prime directive to his developers and team" in a 2009 interview in Business Insider, in which he also said, "Unless you are breaking stuff, you are not moving fast enough."[42]

In 2018, Oculus lead Jason Rubin sent his 50-page vision document titled The Metaverse to Facebook's leadership. In the document, Rubin acknowledges that Facebook's virtual reality business didn't catch on as expected, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on content for early adopters. He also urged the company to execute fast and go big on the vision, to shut out HTC, Apple, Google and other competitors in the VR space. Regarding other players' participation in the metaverse vision, he wrote: “Let’s build the Metaverse to keep them from being in the VR business in a meaningful way at all.”[43]

In May 2019, Facebook founded Libra Networks, reportedly to develop their own stablecoin cryptocurrency.[44] In recent developments it has been reported that Libra is being supported by financial companies like Visa, Mastercard, PayPal and Uber. The consortium of companies is expected to pool in $10 million each to fund the launch of the cryptocurrency coin named Libra.[45] Depending on when it receives approval from the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory authority to operate as a payments service, the Libra Association plans to launch a limited format cryptocurrency in 2021.[46]

Mergers and acquisitions

Throughout its existence, Facebook, Inc./Meta has acquired multiple companies (often identified as talent acquisitions).[47]

One of its first major acquisitions was in April 2012, when it acquired Instagram for approximately US$1 billion in cash and stock.[48]

In October 2013, Facebook, Inc. acquired Onavo, an Israeli mobile web analytics company.[49][50]

In February 2014, Facebook, Inc. announced it would buy mobile messaging company WhatsApp for US$19 billion in cash and stock.[51][52] Later that year, Facebook bought Oculus VR for $2.3 billion in stock and cash,[53] which released its first consumer virtual reality headset in 2016.

In late July 2019, the company announced it was under antitrust investigation by the Federal Trade Commission.[54]

In late November 2019, Facebook, Inc. announced the acquisition of game developer Beat Games, responsible for developing one of the year's most popular VR titles, Beat Saber.[55]

In April 2020, Facebook, Inc. announced a $5.7-billion deal with the Indian multinational conglomerate Reliance Industries to purchase approximately 10 percent of Jio Platforms, Reliance's digital media and services entity.[56]

In May 2020, Facebook, Inc. announced it had acquired Giphy for a reported cash price of $400 million. It will be integrated with the Instagram team.[57] However, in August 2021, UK's Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) stated that Facebook, Inc. might have to sell Giphy, after an investigation found that the deal between the two companies would harm competition in display advertising market.[58] Facebook, Inc. was fined $70 million by CMA for deliberately failing to report all information regarding the acquisition and the ongoing antitrust investigation.[59]

Facebook, Inc. announced in November 2020 that it planned to purchase the customer-service platform and chatbot specialist startup Kustomer to promote companies to use their platform for business. It has been reported that Kustomer valued at slightly over $1 billion.[60]

Lobbying

In 2020, Facebook, Inc. spent $19.7 million on lobbying, hiring 79 lobbyists. In 2019, it had spent $16.7 million on lobbying and had a team of 71 lobbyists, up from $12.6 million and 51 lobbyists in 2018.[61]

Lawsuits

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2020) |

Facebook, Inc./Meta has been involved in multiple lawsuits since its founding.

In March 2020, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) sued Facebook, for significant and persistent infringements of the rule on privacy involving the Cambridge Analytica fiasco. Every violation of the Privacy Act is subject to a theoretical cumulative liability of $1.7 million. The OAIC estimated that a total of 311,127 Australians had been exposed.[62]

On December 8, 2020, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission and 46 states (excluding Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and South Dakota), the District of Columbia and the territory of Guam, launched Federal Trade Commission v. Facebook as an antitrust lawsuit against Facebook. The lawsuit concerns Facebook's acquisition of two competitors—Instagram and WhatsApp—and the ensuing monopolistic situation. FTC alleges that Facebook holds monopolistic power in the US social networking market and seeks to force the company to divest from Instagram and WhatsApp to break up the conglomerate.[63] William Kovacic, a former chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, argued the case will be difficult to win as it would require the government to create a counterfactual argument of an internet where the Facebook-WhatsApp-Instagram entity did not exist, and prove that harmed competition or consumers.[64]

Rebranding

Following a period of intense scrutiny and damaging whistleblower leaks, news started to emerge on October 21, 2021 about Facebook's plan to rebrand the company and to change its name.[65][66] In the Q3 2021 Earnings Call, on October 25, Mark Zuckerberg discussed the ongoing criticism of the company's social services and the way it operates, and pointed to the pivoting efforts to building the metaverse - without mentioning the rebranding and the name change.[67] The metaverse vision and the name change from Facebook, Inc. to Meta Platforms was introduced at Facebook Connect on October 28, 2021.[68] Based on Facebook's PR campaign, the name change reflects the company's shifting long term focus of building the metaverse, a digital extension of the physical world by social media, virtual reality and augmented reality features.[68][69]

"Meta" had been registered as a trademark in the United States in 2018 (after an initial filing in 2015) for marketing, advertising, and computer services, by a Canadian company that provided big data analysis of scientific literature.[70] This company had been acquired in 2017 by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), a foundation established by Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan, and became one of their projects.[71] Following the Facebook/Meta rebranding announcement, CZI announced that it had already decided to deprioritize the earlier Meta project, that it would be transferring its rights to the name to Meta Platforms, and that the project would be sunset in 2022.[72]

Structure

Management

Meta's key management consists of:[73]

- Mark Zuckerberg, chairman and chief executive officer

- Sheryl Sandberg, Chief Operating Officer

- Mike Schroepfer, Chief Technology Officer

- David Wehner, Chief Financial Officer

- Chris Cox, Chief Product Officer[74]

As of December 2020[update], Meta had 58,604 employees, an increase of 30.4% year-over-year.[75]

Board of directors

As of October 2021, Meta's board consisted of the following directors;[73]

- Mark Zuckerberg (chairman, founder and CEO)

- Sheryl Sandberg (executive director and COO)

- Peggy Alford (non-executive director, executive vice president, global sales, PayPal)

- Marc Andreessen (non-executive director, co-founder and general partner, Andreessen Horowitz)

- Drew Houston (non-executive director, chairman and CEO, Dropbox)

- Nancy Killefer (non-executive director, senior partner, McKinsey & Company)

- Robert M. Kimmitt (non-executive director, senior international counsel, WilmerHale)

- Peter Thiel (non-executive director, co-founder and former CEO, PayPal, founder and president, Clarium Capital)

- Tracey Travis (non-executive director, executive vice president, chief financial officer, Estée Lauder Companies)

Company governance

Early Facebook investor and former Zuckerberg mentor Roger McNamee described Facebook as having "the most centralized decision-making structure I have ever encountered in a large company."[76] Nathan Schneider, a professor of media studies at the University of Colorado Boulder argued for transforming Facebook into a platform cooperative owned and governed by the users.[77]

Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes has stated that CEO Mark Zuckerberg has too much power, that the company is now a monopoly, and that, as a result, it should be split into multiple smaller companies. In an op-ed in The New York Times, Hughes said he was concerned that Zuckerberg had surrounded himself with a team that did not challenge him, and that it is the U.S. government's job to hold him accountable and curb his "unchecked power."[78] He also said that "Mark's power is unprecedented and unamerican."[79] Several U.S. politicians agreed with Hughes.[80] European Union Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager stated that splitting Facebook should be done only as "a remedy of the very last resort", and that it would not solve Facebook's underlying problems.[81]

Revenue

| Year | Revenue | Growth |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | $0.4[82] | — |

| 2005 | $9[82] | 2150% |

| 2006 | $48[82] | 433% |

| 2007 | $153[82] | 219% |

| 2008 | $280[83] | 83% |

| 2009 | $775[84] | 177% |

| 2010 | $2,000[85] | 158% |

| 2011 | $3,711[86] | 86% |

| 2012 | $5,089[87] | 37% |

| 2013 | $7,872[87] | 55% |

| 2014 | $12,466[88] | 58% |

| 2015 | $17,928[89] | 44% |

| 2016 | $27,638[90] | 54% |

| 2017 | $40,653[91] | 47% |

| 2018 | $55,838[92] | 38% |

| 2019 | $70,697[93] | 27% |

| 2020 | $85,965[94] | 22% |

Facebook ranked No. 34 in the 2020 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by revenue, with almost $86 billion in revenue.[95] Most comes from advertising.[96][97] One analysis of 2017 data determined that the company earned US$20.21 per user from advertising.[98]

Number of advertisers

In February 2015, Facebook announced it had reached two million active advertisers, with most of the gain coming from small businesses. An active advertiser was defined as an entity that had advertised on the Facebook platform in the last 28 days.[99] In March 2016, Facebook announced it had reached three million active advertisers with more than 70% from outside the United States.[100] Prices for advertising follow a variable pricing model based on auctioning ad placements, and potential engagement levels of the advertisement itself. Similar to other online advertising platforms like Google and Twitter, targeting of advertisements is one of the chief merits of digital advertising compared to traditional media. Marketing on Meta is employed through two methods based on the viewing habits, likes and shares, and purchasing data of the audience, namely targeted audiences and "look alike" audiences.[101]

Tax affairs

The US IRS challenged the valuation Facebook used when it transferred IP from the US to Facebook Ireland in 2010 (which Facebook Ireland then revalued higher before charging out), as it was building its double Irish tax structure.[102][103] The case is ongoing and Meta faces a potential fine of $3–5bn.[104]

The US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 changed Facebook's global tax calculations. Facebook Ireland is subject to the US GILTI tax of 10.5% on global intangible profits (i.e. Irish profits). On the basis that Facebook Ireland is paying some tax, the effective minimum US tax for Facebook Ireland will be circa 11%. In contrast, Meta Inc. would incur a special IP tax rate of 13.125% (the FDII rate) if its Irish business relocated to the US. Tax relief in the US (21% vs. Irish at the GILTI rate) and accelerated capital expensing, would make this effective US rate around 12%.[105][106][107]

The insignificance of the US/Irish tax difference was demonstrated when Facebook moved 1.5bn non-EU accounts to the US to limit exposure to GDPR.[108][109]

Facilities

Offices

Users outside of the US and Canada contract with Meta's Irish subsidiary, Facebook Ireland Limited, allowing Meta to avoid US taxes for all users in Europe, Asia, Australia, Africa and South America. Meta is making use of the Double Irish arrangement which allows it to pay 2–3% corporation tax on all international revenue.[110] In 2010, Facebook opened its fourth office, in Hyderabad, India,[111] which houses online advertising and developer support teams and provides support to users and advertisers.[112] In India, Meta is registered as Facebook India Online Services Pvt Ltd.[113] It also has support centers in Chittagong; Dublin;[clarification needed] California; Ireland; and Austin, Texas.[114][not specific enough to verify]

Facebook opened its London headquarters in 2017 in Fitzrovia in central London. Facebook opened an office in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2018. The offices were initially home to the "Connectivity Lab", a group focused on bringing Internet access to those who do not have access to the Internet.[115]

Entrance to Facebook's previous headquarters in the Stanford Research Park, Palo Alto, California

Data centers

As of 2019, Facebook operated 16 data centers.[116] It committed to purchase 100% renewable energy and to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 75% by 2020.[117] Its data center technologies include Fabric Aggregator, a distributed network system that accommodates larger regions and varied traffic patterns.[118]

Reception

US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez responded in a tweet to Zuckerberg's announcement about Meta, saying "Meta as in 'we are a cancer to democracy metastasizing into a global surveillance and propaganda machine for boosting authoritarian regimes and destroying civil society… for profit!'"[119]

Ex-Facebook employee Frances Haugen and whistleblower behind the Facebook Papers responded to the rebranding efforts by expressing doubts about the company's ability to improve while led by Mark Zuckerberg, and urged the CEO to resign.[120]

See also

References

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis C. (January 31, 2012). "Facebook's Very First SEC Filing". The Atlantic. Washington, D.C. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Zuckerberg, Mark (October 1, 2010). "Eleventh Amended and Restated Certificate of Incorporation of Facebook, Inc". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ "Chris Cox is returning to Facebook as chief product officer". The Verge. June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Facebook is getting more serious about becoming your go-to for mobile payments". The Verge. August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ "Our History". Facebook. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Shaban, Hamza (January 20, 2019). "Digital advertising to surpass print and TV for the first time, report says". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ "FB Income Statement". NASDAQ.com.

- ^ "FB Balance Sheet". NASDAQ.com.

- ^ "Stats". Facebook. June 30, 2019. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook - Financials". investor.fb.com. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "Delaware Corporate Entity Search". Retrieved October 28, 2021. (file no. 3835815)

- ^ Meta Platforms, Inc. (October 28, 2021). "Current Report (8-K)". Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ Haq, Sana Noor (October 30, 2021). "Hebrew speakers mock Facebook's corporate rebrand to Meta". CNN. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook Inc. Certificate of Incorporation" (PDF). September 1, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

File Number 3835815

- ^ "Facebook Reports Second Quarter 2021 Results". investor.fb.com. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ Facebook, Inc. (January 28, 2021). "Form 10-K (2021)" (PDF). Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook Invests $5.7 Billion in Indian Internet Giant Jio". The New York Times. April 22, 2020. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- ^ Heath, Alex (October 19, 2021). "Facebook is planning to rebrand the company with a new name". The Verge. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Dwoskin, Elizabeth (October 28, 2021). "Facebook is changing its name to Meta as it focuses on the virtual world". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook announces name change to Meta in rebranding effort". The Guardian. October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook changes its name to Meta as a part of rebrand | Programming Nation". Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ "Form S-1 Registration Statement Under The Securities Act of 1933". January 1, 2012. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Erickson, Christine (January 3, 2012). "Facebook IPO: The Complete Guide". Mashable business. Retrieved March 23, 2012.

- ^ Helft, Miguel; Hempel, Jessi (March 19, 2012). "Inside Facebook". Fortune. 165 (4): 122. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ^ Tangel, Andrew; Hamilton, Walter (May 17, 2012). "Stakes are high on Facebook's first day of trading". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ "Facebook boosts number of shares on offer by 25%". BBC News. May 16, 2012. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Rusli, Evelyn M.; Eavis, Peter (May 17, 2012). "Facebook Raises $16 Billion in I.P.O." The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Condon, Bernard (May 17, 2012). "Questions and answers on blockbuster Facebook IPO". U.S. News. Associated Press. Retrieved May 17, 2012.[permanent dead link] Alternate Link Archived

- ^ Gross, Doug (March 17, 2012). "Internet greets Facebook's IPO price with glee, skepticism". CNN. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- ^ Straburg, Jenny; Bunge, Jacob (May 18, 2012). "Trading Problems Persisted After Opening for Facebook's IPO". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Bunge, Jacob; Strasburg, Jenny; Dezember, Ryan (May 18, 2012). "Facebook Falls Back to IPO Price". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Michael J. De La Mercred (May 18, 2012). "Facebook Closes at $38.23, Nearly Flat on Day". The New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ O'Dell, Jolie (May 18, 2012). "Facebook disappoints on its opening day, closing down $4 from where it opened". Venture Beat. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ "Facebook Sets Record For IPO Trading Volume". The Wall Street Journal. May 18, 2012. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ^ Womack, Brian; Thomson, Amy (May 21, 2012). "Facebook falls below $38 IPO price in second day of trading". The Washington Post. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Evelyn M. Rusli and Michael J. De La Merced (May 22, 2012). "Facebook I.P.O. Raises Regulatory Concerns". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ Temple, James; Newton, Casey (May 23, 2012). "Litigation over Facebook IPO just starting". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ Eichler, Alexander (May 24, 2012). "Wall St. Cashes In On Facebook Stock Plunge While Ordinary Investors Lose Millions". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Facebook to join S&P 500". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ Baer, Drake. "Mark Zuckerberg Explains Why Facebook Doesn't 'Move Fast And Break Things' Anymore". Business Insider.

- ^ "Facebook can't move fast to fix the things it broke". Engadget.

- ^ Blodget, Henry (October 1, 2009). "Mark Zuckerberg On Innovation". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ https://www.cnbc.com/2021/10/30/facebooks-meta-mission-was-laid-out-in-a-2018-paper-on-the-metaverse.html

- ^ "Bitcoin Above $8,000; Facebook Opens Crypto Company in Switzerland". Investing.com. May 20, 2019.

- ^ Reiff, Nathan. "Facebook Gathers Companies to Back Cryptocurrency Launch". Investopedia. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Hannah (November 27, 2020). "Facebook's Libra currency to launch next year in limited format". Financial Times.

- ^ Helft, Miguel (May 17, 2011). "For Buyers of Web Start-Ups, Quest to Corral Young Talent". The New York Times. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook buys Instagram for $1 billion". weebly. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Lunden, Ingrid (October 13, 2013). "Facebook Buys Mobile Data Analytics Company Onavo, Reportedly For Up To $200M… And (Finally?) Gets Its Office In Israel". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Rosen, Guy (November 7, 2013). "We are joining the Facebook team". Onavo Blog. Archived from the original on November 7, 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Covert, Adrian (January 19, 2014). "Facebook buys WhatsApp for $19 billion". CNNMoney. CNN. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Stone, Brad (February 20, 2014). "Facebook Buys WhatsApp for $19 Billion". Bloomberg. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (March 25, 2014). "Facebook Buys Oculus Rift For $2 Billion". Kotaku.com. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Cox, Kate (July 25, 2019). "The FTC is investigating Facebook. Again". ars Technica. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^ Marshall, Cass (November 26, 2019). "Facebook acquires Beat Saber developer". Polygon.

- ^ Bhattacharjee, Nivedita; Phartiyal, Sankalp (April 22, 2020). "Facebook bets on India with $5.7 billion Reliance deal". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Abram. "Facebook Buys Giphy For $400 Million". Forbes. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Aripaka, Pushkala (August 12, 2021). "Facebook may have to sell Giphy on Britain's competition concerns". Reuters. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Lomas, Natasha (October 20, 2021). "Facebook fined $70M for flouting Giphy order made by UK watchdog". TechCrunch. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ Cimilluca, Cara Lombardo and Dana (November 30, 2020). "WSJ News Exclusive | Facebook to Buy customer, Startup Valued at $1 Billion". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ "Client Profile: Facebook Inc". Center for Responsive Politics. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook suffers blow in Australia legal fight over Cambridge Analytica". The Guardian. September 14, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren; Rodriguez, Salvador (December 8, 2020). "FTC and states sue Facebook, could force it to divest Instagram and WhatsApp". CNBC. Archived from the original on December 13, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Fung, Brian. "The legal battle to break up Facebook is underway. Now comes the hard part". CNN. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ "Facebook is planning to rebrand the company with a new name". October 19, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook's reported name change reinforces its image as the new Big Tobacco". October 21, 2021.

- ^ https://s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_financials/2021/q3/FB-Q3-2021-Earnings-Call-Transcript.pdf

- ^ a b "The Facebook Company is Now Meta". October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Mark Zuckerberg on why Facebook is rebranding to Meta". October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Trademark Status & Document Retrieval (serial no. 86852664)". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Constine, Josh (January 23, 2017). "Chan Zuckerberg Initiative acquires and will free up science search engine Meta". TechCrunch. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Gonzalez, Oscar (October 28, 2021). "Chan Zuckerberg Initiative to sunset its Meta project". CNET. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Facebook Management". Facebook Investor Relations. Facebook. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ "Chris Cox is returning to Facebook as chief product officer". The Verge. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ H., Tankovska (June 30, 2020). "Number of Facebook employees 2004-2020". Statista.com. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Bissell, Tom (January 29, 2019). "An Anti-Facebook Manifesto, by an Early Facebook Investor". Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Schneider, Nathan; Cheadle, Harry (March 27, 2018). "It's Time for Mark Zuckerberg to Give Up Control of Facebook". Vice.

- ^ Brown, Shelby. "Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes calls for company's breakup". CNET.

- ^ Hughes, Chris (May 9, 2019). "Opinion | It's Time to Break Up Facebook". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Brown, Shelby. "More politicians side with Facebook co-founder on breaking up company". CNET. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Collins, Katie. "EU competition commissioner: Facebook breakup would be 'last resort'". CNET. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Tsotsis, Alexia (February 1, 2012). "Facebook's IPO: An End To All The Revenue Speculation". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Arrington, Michael (May 19, 2009). "Facebook Turns Down $8 billion Valuation Term Sheet, Claims 2009 Revenues Will Be $550 million". TechCrunch. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ Tsotsis, Alexia (January 5, 2011). "Report: Facebook Revenue Was $777 Million In 2009, Net Income $200 Million". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ Womack, Brian (December 16, 2010). "Facebook 2010 Sales Said Likely to Reach $2 Billion, More Than Estimated". Bloomberg. New York. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2012 Results". Facebook. Facebook. January 30, 2013. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2013 Results". Facebook. Facebook. January 29, 2014. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2014 Results". Facebook. Facebook. Archived from the original on January 29, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2015 Results". Facebook. Facebook. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ "Facebook Annual Report 2016" (PDF). Facebook. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2017 Results". Facebook. Facebook. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2018 Results". investor.fb.com. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2018 Results". investor.fb.com. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2020 Results". investor.fb.com. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Facebook | 2021 Fortune 500". Fortune. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Jolie O'Dell 203 (January 17, 2011). "Facebook's Ad Revenue Hit $1.86B for 2010". Mashable. Mashable.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Womack, Brian (September 20, 2011). "Facebook Revenue Will Reach $4.27 Billion, EMarketer Says". bloomberg. Bloomberg. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Malloy, Daniel (May 27, 2019). "Too Big Not To Fail?". OZY. What's your online data really worth? About $5 a month. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Meola, Andrew (February 24, 2015). "Active, in this case, means the advertiser has advertised on the site in the last 28 days". TheStreet. TheStreet, Inc. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ "3 Million Advertisers on Facebook". Facebook for Business.

- ^ "Complete interview with Brad Parscale and the Trump marketing strategy". PBS Frontline.

- ^ "Facebook must give judge documents for U.S. tax probe of Irish unit". Reuters. March 28, 2018. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook's Dublin HQ central to $5bn US tax probe". Sunday Business Post. April 1, 2018. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook Ordered to Comply With U.S. Tax Probe of Irish Unit". Bloomberg. Bloomberg News. March 28, 2018. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "KPMG Report on TCJA" (PDF). KPMG. February 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Breaking Down the New U.S. Corporate Tax Law". Harvard Business Review. December 26, 2017. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "US corporations could be saying goodbye to Ireland". The Irish Times. January 17, 2018. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Exclusive: Facebook to put 1.5 billion users out of reach of new EU privacy law". Reuters News. April 19, 2018. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Facebook moves 1.5bn users out of reach of new European privacy law". The Guardian. London. April 19, 2018.

- ^ Drucker, Jesse (October 21, 2010). "Google 2.4% Rate Shows How $60 Billion Lost to Tax Loopholes". Bloomberg. Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ PTI (September 30, 2010). "Facebook opens office in India". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Facebook's Hyderabad Office Inaugurated – Google vs Facebook Battle Comes To India". Watblog.com. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Not responsible for user-generated content hosted on website: Facebook India". Articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com. February 29, 2012. Archived from the original on May 14, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Zuckerberg at Ore. Facebook data center". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. April 16, 2011. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Nanos, Janelle (August 30, 2017). "Facebook to open new office in Kendall Square, adding hundreds of jobs". The Boston Globe. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "Facebook Data Center Locations". Baxtel.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "On Our Way to Lower Emissions and 100% Renewable Energy". Facebook Newsroom. August 28, 2018.

- ^ "Data centers: 2018 year in review". Facebook Code. January 1, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ https://qz.com/2082271/how-facebooks-meta-branding-might-accidentally-kill-the-overall-metaverse/

- ^ https://www.reuters.com/technology/facebook-whistleblower-haugen-sees-no-sense-meta-rebrand-2021-11-01/

External links

- Official website

- Meta Platforms companies grouped at OpenCorporates

- Business data for Meta Platforms, Inc.:

- "Facebook Inc's 10-K filed in 2017, listing business "risk factors". www.sec.gov. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

About the page

Presented content of the Wikipedia article was extracted in 2021-11-04 based on https://en.wikipedia.org/?curid=62420226