Favipiravir

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Avigan (アビガン, Abigan), Avifavir,[1] Areplivir,[2] others |

| Other names | T-705, favipira, favilavir |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

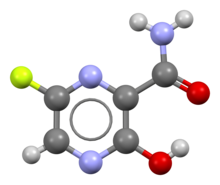

| Formula | C5H4FN3O2 |

| Molar mass | 157.104 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (March 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Favipiravir, sold under the brand name Avigan among others,[3] is an antiviral medication used to treat influenza in Japan.[4] It is also being studied to treat a number of other viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2.[4] Like the experimental antiviral drugs T-1105 and T-1106, it is a pyrazinecarboxamide derivative.[5]

It is being developed and manufactured by Toyama Chemical (a subsidiary of Fujifilm) and was approved for medical use in Japan in 2014.[6] In 2016, Fujifilm licensed it to Zhejiang Hisun Pharmaceutical Co. of China.[7] It became a generic drug in 2019, allowing the company to produce it in the People's Republic of China.[citation needed]

Medical use

Favipiravir has been approved to treat influenza in Japan.[6] It is, however, only indicated for novel influenza (strains that cause more severe disease) rather than seasonal influenza.[6] As of 2020, the probability of resistance developing appears low.[6]

Side effects

There is evidence that use during pregnancy may result in harm to the baby.[6] Teratogenic and embryotoxic effects were shown on four animal species.[6][8]

Mechanism of action

The mechanism of its actions is thought to be related to the selective inhibition of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.[9][medical citation needed] Favipiravir is a prodrug that is metabolized to its active form, favipiravir-ribofuranosyl-5'-triphosphate (favipiravir-RTP), available in both oral and intravenous formulations.[10][11] In 2014, favipiravir was approved in Japan for stockpiling against influenza pandemics.[12] However, favipiravir has not been shown to be effective in primary human airway cells, casting doubt on its efficacy in influenza treatment.[13]

Favipiravir-RTP is a nucleoside analogue. It mimics both guanosine and adenosine for the viral RdRP. Incorporating two such bases in a row stops primer extension, although it's unclear how as of 2013.[9]

Society and culture

Legal status

The US Department of Defense developed favipiravir in partnership with MediVector, Inc. as a broad-spectrum antiviral and sponsored it through FDA Phase II and Phase III clinical trials, where it demonstrated safety in humans and efficacy against the influenza virus.[14] Despite demonstrating safety in more than 2,000 patients and showing accelerated clearance of influenza virus by 6 to 14 hours in the unpublished Phase III trials[citation needed], favipiravir remains unapproved in the UK and the USA.[15] In 2014, Japan approved favipiravir for treating influenza strains unresponsive to current antivirals.[16] Toyama Chemical initially hoped that favipiravir would become a new influenza medication that could replace oseltamivir (brand name Tamiflu). However, animal experiments show the potential for teratogenic effects, and the approval of production by The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare was greatly delayed and the production condition is limited only in an emergency in Japan.[17]

Despite limited data on efficacy, as of March 2021 favipiravir is widely prescribed for outpatient treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in Hungary.[18] Patients are required to sign a consent form before obtaining the drug.

Brand names

Favipiravir is sold under the brand names Avigan (アビガン, Abigan), Avifavir,[1] Areplivir,[2] FabiFlu,[19] and Favipira.[20]

Research

COVID-19

Fabipravir, as an antiviral drug, has been authorized for treating COVID-19 in several countries including Japan, Russia, and India, under emergency provisions.[21][22][23] A rapid meta-review in September 2020 (analyzing four studies) noted that the drug led to clinical and radiological improvements; however, no reduction in mortality or differences in oxygen-support requirement were observed and more rigorous studies were sought.[24][25]

As of May 2021[update], large-cohort clinical trials are underway.[26]

Ebola

Research in 2014, suggested that favipiravir may have efficacy against Ebola based on studies in mouse models; efficacy in humans was unaddressed.[27][28][29]

During the 2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak, a French nurse who contracted Ebola while volunteering for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Liberia reportedly recovered after receiving a course of favipiravir.[30] A clinical trial investigating the use of favipiravir against Ebola virus disease began in Guéckédou, Guinea, in December 2014.[31] Preliminary results presented in 2016 at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), later published, showed a decrease in mortality in patients with low-to-moderate levels of virus in blood, but no effect on patients with high levels (the group at a higher risk of death).[32][33][34] The trial design was concomitantly criticised for using only historical controls.[35]

Nipah

Nipah virus is a causative agent of outbreaks of encephalitis with pneumonia and has a high case fatality rate. The first outbreak occurred in Malaysia-Singapore, related to contact with pigs in slaughterhouses and an outbreak in Philippines related to slaughter of horses, most other outbreaks have affected India and Bangladesh. in Bangladesh outbreaks are often associated with consumption of raw date palm sap contaminated by saliva and urine of fruit bats.[36] In a study published in the Scientific Reports, Syrian hamster model for Nipah virus infection was used, which closely mirrors most aspects of human disease, such as widespread vasculitis, pneumonia, and encephalitis. The hamsters were infected with a lethal dose of 104 PFU NiV-M via the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route similar to previous studies and treatment was initiated immediately after infection. Favipiravir was administered twice daily via the peroral (p.o.) route for 14 days. The treated hamsters displayed 100% survival and no obvious morbidity after lethal NiV challenge, whereas all the control cases died of severe disease.[37]

Other

In experiments in animals favipiravir has shown activity against West Nile virus, yellow fever virus, foot-and-mouth disease virus as well as other flaviviruses, arenaviruses, bunyaviruses and alphaviruses.[38] Activity against enteroviruses[39] and Rift Valley fever virus has also been demonstrated.[40] Favipiravir has showed limited efficacy against Zika virus in animal studies, but was less effective than other antivirals such as MK-608.[41] The agent has also shown some efficacy against rabies,[42] and has been used experimentally in some humans infected with the virus.[43]

Tautomerism

The possible tautomerism of favipiravir has been investigated computationally. It was found that the enol-like form was substantially more stable in aqueous solution than the keto-like form, meaning that Favipiravir likely exists almost exclusively in the enol-like form in aqueous solution. Upon protonation the keto form is switched on. However these findings were caveated with the need to confirm this experimentally.[44]

References

- ^ a b "Avifavir". Russian drug reference. Medum.ru.

- ^ a b "Arelpivir". Russian drug reference. Medum.ru.

- ^ https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/glenmark-launches-covid-19-drug-fabiflu-priced-at-rs-103-per-tablet-120062000872_1.html

- ^ a b Du YX, Chen XP (April 2020). "Favipiravir: pharmacokinetics and concerns about clinical trials for 2019-nCoV infection". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 108 (2): 242–247. doi:10.1002/cpt.1844. PMID 32246834.

- ^ Furuta, Yousuke; Takahashi, Kazumi; Shiraki, Kimiyasu; Sakamoto, Kenichi; Smee, Donald F.; Barnard, Dale L.; Gowen, Brian B.; Julander, Justin G.; Morrey, John D. (2009). "T-705 (Favipiravir) and related compounds: Novel broad-spectrum inhibitors of RNA viral infections". Antiviral Research. 82 (3): 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.02.198. PMC 7127082. PMID 19428599.

- ^ a b c d e f Shiraki K, Daikoku T (February 2020). "Favipiravir, an anti-influenza drug against life-threatening RNA virus infections". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 209: 107512. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107512. PMC 7102570. PMID 32097670.

- ^ EJ Lane (June 22, 2016). "Fujifilm in Avigan API license with Zhejiang Hisun Pharmaceuticals". Fierce Pharma. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Pilkington, Victoria; Pepperrell, Toby; Hill, Andrew (2020). "A review of the safety of favipiravir – a potential treatment in the COVID-19 pandemic?". Journal of Virus Eradication. 6 (2): 45–51. doi:10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30016-9. ISSN 2055-6640. PMC 7331506. PMID 32405421.

- ^ a b Jin Z, Smith LK, Rajwanshi VK, Kim B, Deval J (2013). "The ambiguous base-pairing and high substrate efficiency of T-705 (Favipiravir) Ribofuranosyl 5'-triphosphate towards influenza A virus polymerase". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e68347. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...868347J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068347. PMC 3707847. PMID 23874596.

- ^ Guedj J, Piorkowski G, Jacquot F, Madelain V, Nguyen TH, Rodallec A, et al. (March 2018). "Antiviral efficacy of favipiravir against Ebola virus: A translational study in cynomolgus macaques". PLOS Medicine. 15 (3): e1002535. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002535. PMC 5870946. PMID 29584730.

- ^ Smee DF, Hurst BL, Egawa H, Takahashi K, Kadota T, Furuta Y (October 2009). "Intracellular metabolism of favipiravir (T-705) in uninfected and influenza A (H5N1) virus-infected cells". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 64 (4): 741–6. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp274. PMC 2740635. PMID 19643775.

- ^ Koons C (7 August 2014). "Ebola Drug From Japan May Emerge Among Key Candidates". Bloomberg.com.

- ^ Yoon JJ, Toots M, Lee S, Lee ME, Ludeke B, Luczo JM, et al. (August 2018). "Orally Efficacious Broad-Spectrum Ribonucleoside Analog Inhibitor of Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Viruses". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 62 (8): e00766–18. doi:10.1128/AAC.00766-18. PMC 6105843. PMID 29891600.

- ^ "MediVector Completes Patient Enrollment In Two Phase 3 Studies Of Favipiravir For Influenza". BioSpace. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Lumby, Casper (3 March 2020). "Favipiravir and Zanamivir Cleared Infection with Influenza B in a Severely Immunocompromised Child". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 71 (7): e191–e194. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa023. PMID 32124919.

- ^ Hayden FG, Shindo N (April 2019). "Influenza virus polymerase inhibitors in clinical development". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 32 (2): 176–186. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000532. PMC 6416007. PMID 30724789.

- ^ 条件付き承認で普及に足かせ 富山化学インフル薬の"無念" (in Japanese). Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "A kórházakat tehermentesítheti az egyforintos koronavírus-gyógyszer". telex (in Hungarian). 2021-03-11. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ "'FabiFlu is the most economical COVID-19 treatment option': Glenmark's reply to Centre on alleged 'overpricing'". DNA India. 21 July 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ "Favipira - Tablet - 200 mg - Beacon Pharmaceuticals Ltd. - Indications, Pharmacology, Dosage, Side Effects & other Generic Info". Medex. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Ueda, Munetaka; Tanimoto, Tetsuya; Murayama, Anju; Ozaki, Akihiko; Kami, Masahiro. "Japan's Drug Regulation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons From a Case Study of Favipiravir". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1002/cpt.2251. ISSN 1532-6535.

- ^ Staff, Reuters (2020-09-18). "Russia approves first COVID-19 prescription drug for sale in pharmacies". Reuters. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Pulla, Priyanka (2020-11-25). "Is Favipiravir Good for COVID-19? Clinical Trial Says No, Press Release Says Yes". The Wire Science. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Vaidyanathan, Gayathri (2020-11-09). "Scientists criticize use of unproven COVID drugs in India". Nature. 587 (7833): 187–188. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03105-7.

- ^ Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Khadka S, Shah PB, Pokharel N, Rashmi P (September 2020). "Favipiravir versus other antiviral or standard of care for COVID-19 treatment: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis". Virol J. 17 (1): 141. doi:10.1186/s12985-020-01412-z. PMC 7512218. PMID 32972430.

- ^ "Favipiravir to be investigated as a possible COVID-19 treatment for at-home recovery in the PRINCIPLE trial". PRINCIPLE Trial. 8 April 2021.

Led by University of Oxford researchers, PRINCIPLE is one of the UK Government's national priority platform trials for COVID-19 treatments and was set-up with the intention that drugs shown to have a clinical benefit could be rapidly introduced into routine NHS care.

- ^ Gatherer D (August 2014). "The 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa". The Journal of General Virology. 95 (Pt 8): 1619–1624. doi:10.1099/vir.0.067199-0. PMID 24795448.

- ^ Oestereich L, Lüdtke A, Wurr S, Rieger T, Muñoz-Fontela C, Günther S (May 2014). "Successful treatment of advanced Ebola virus infection with T-705 (favipiravir) in a small animal model". Antiviral Research. 105: 17–21. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.02.014. PMID 24583123.

- ^ Smither SJ, Eastaugh LS, Steward JA, Nelson M, Lenk RP, Lever MS (April 2014). "Post-exposure efficacy of oral T-705 (Favipiravir) against inhalational Ebola virus infection in a mouse model". Antiviral Research. 104: 153–5. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.01.012. PMID 24462697.

- ^ "First French Ebola patient leaves hospital". Reuters. 4 October 2016.

- ^ "Guinea: Clinical Trial for Potential Ebola Treatment Started in MSF Clinic in Guinea". AllAfrica – All the Time. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ "Favipiravir in Patients with Ebola Virus Disease: Early Results of the JIKI trial in Guinea". CROIconference.org. Retrieved 2016-03-17.

- ^ Sissoko D, Laouenan C, Folkesson E, M'Lebing AB, Beavogui AH, Baize S, et al. (March 2016). "Experimental Treatment with Favipiravir for Ebola Virus Disease (the JIKI Trial): A Historically Controlled, Single-Arm Proof-of-Concept Trial in Guinea". PLOS Medicine. 13 (3): e1001967. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001967. PMC 4773183. PMID 26930627.

- ^ Fink S (4 February 2015). "Ebola Drug Aids Some in a Study in West Africa". The New York Times.

- ^ Cohen J (26 February 2015). "Results from encouraging Ebola trial scrutinized". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaa7912. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Banerjee, Sayantan; Gupta, Nitin; Kodan, Parul; Mittal, Ankit; Ray, Yogiraj; Nischal, Neeraj; Soneja, Manish; Biswas, Ashutosh; Wig, Naveet (February 2019). "Nipah virus disease: A rare and intractable disease". Intractable & Rare Diseases Research. 8 (1): 1–8. doi:10.5582/irdr.2018.01130. ISSN 2186-3644. PMC 6409114. PMID 30881850.

- ^ Dawes, Brian E.; Kalveram, Birte; Ikegami, Tetsuro; Juelich, Terry; Smith, Jennifer K.; Zhang, Lihong; Park, Arnold; Lee, Benhur; Komeno, Takashi; Furuta, Yousuke; Freiberg, Alexander N. (15 May 2018). "Favipiravir (T-705) protects against Nipah virus infection in the hamster model". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 7604. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.7604D. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25780-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5954062. PMID 29765101.

- ^ Furuta Y, Takahashi K, Shiraki K, Sakamoto K, Smee DF, Barnard DL, et al. (June 2009). "T-705 (favipiravir) and related compounds: Novel broad-spectrum inhibitors of RNA viral infections". Antiviral Research. 82 (3): 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.02.198. PMC 7127082. PMID 19428599.

- ^ Furuta Y, Gowen BB, Takahashi K, Shiraki K, Smee DF, Barnard DL (November 2013). "Favipiravir (T-705), a novel viral RNA polymerase inhibitor". Antiviral Research. 100 (2): 446–54. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.015. PMC 3880838. PMID 24084488.

- ^ Caroline AL, Powell DS, Bethel LM, Oury TD, Reed DS, Hartman AL (April 2014). "Broad spectrum antiviral activity of favipiravir (T-705): protection from highly lethal inhalational Rift Valley Fever". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (4): e2790. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002790. PMC 3983105. PMID 24722586.

- ^ Mumtaz N, van Kampen JJ, Reusken CB, Boucher CA, Koopmans MP (2016). "Zika Virus: Where Is the Treatment?". Current Treatment Options in Infectious Diseases. 8 (3): 208–211. doi:10.1007/s40506-016-0083-7. PMC 4969322. PMID 27547128.

- ^ Yamada K, Noguchi K, Komeno T, Furuta Y, Nishizono A (April 2016). "Efficacy of Favipiravir (T-705) in Rabies Postexposure Prophylaxis". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 213 (8): 1253–61. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv586. PMC 4799667. PMID 26655300.

- ^ Murphy J, Sifri CD, Pruitt R, Hornberger M, Bonds D, Blanton J, et al. (January 2019). "Human Rabies - Virginia, 2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 67 (5152): 1410–1414. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm675152a2. PMC 6334827. PMID 30605446.

- ^ Antonov L (2020). "Favipiravir tautomerism: a theoretical insight". Theoretical Chemistry Accounts. 139 (8): 145. doi:10.1007/s00214-020-02656-2. PMC 7415411. PMID 32834770.

External links

| Scholia has a profile for favipiravir (Q16934561). |

- "Favipiravir". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

About the page

Presented content of the Wikipedia article was extracted in 2021-06-12 based on https://en.wikipedia.org/?curid=40872327