Coronavirus

| Orthocoronavirinae | |

|---|---|

| |

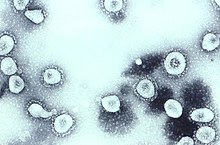

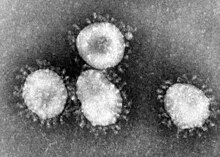

| Transmission electron micrograph of Avian coronavirus | |

| |

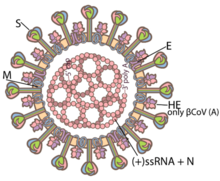

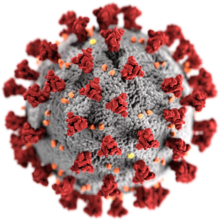

| Illustration of a coronavirus[2] Red: spike proteins (S) Yellow: envelope proteins (E) Orange: membrane proteins (M)

| |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Nidovirales |

| Family: | Coronaviridae |

| Subfamily: | Orthocoronavirinae |

| Genera[1] | |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

| |

Coronaviruses are a group of related RNA viruses that cause diseases in mammals and birds. In humans and birds, they cause respiratory tract infections that can range from mild to lethal. Mild illnesses in humans include some cases of the common cold (which is also caused by other viruses, predominantly rhinoviruses), while more lethal varieties can cause SARS, MERS, and COVID-19. In cows and pigs they cause diarrhea, while in mice they cause hepatitis and encephalomyelitis.

Coronaviruses constitute the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae, in the family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales, and realm Riboviria.[4][5] They are enveloped viruses with a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome and a nucleocapsid of helical symmetry.[6] The genome size of coronaviruses ranges from approximately 26 to 32 kilobases, one of the largest among RNA viruses.[7] They have characteristic club-shaped spikes that project from their surface, which in electron micrographs create an image reminiscent of the solar corona, from which their name derives.[8]

Etymology

The name "coronavirus" is derived from Latin corona, meaning "crown" or "wreath", itself a borrowing from Greek κορώνη korṓnē, "garland, wreath".[9][10] The name was coined by June Almeida and David Tyrrell who first observed and studied human coronaviruses.[11] The word was first used in print in 1968 by an informal group of virologists in the journal Nature to designate the new family of viruses.[8] The name refers to the characteristic appearance of virions (the infective form of the virus) by electron microscopy, which have a fringe of large, bulbous surface projections creating an image reminiscent of the solar corona or halo.[8][11] This morphology is created by the viral spike peplomers, which are proteins on the surface of the virus.[12]

The scientific name Coronavirus was accepted as a genus name by the International Committee for the Nomenclature of Viruses (later renamed International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses) in 1971.[13] As the number of new species increased, the genus was split into four genera, namely Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Deltacoronavirus, and Gammacoronavirus in 2009.[14] The common name coronavirus is used to refer to any member of the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae.[5] As of 2020, 45 species are officially recognised.[15]

History

The earliest reports of a coronavirus infection in animals occurred in the late 1920s, when an acute respiratory infection of domesticated chickens emerged in North America.[16] Arthur Schalk and M.C. Hawn in 1931 made the first detailed report which described a new respiratory infection of chickens in North Dakota. The infection of new-born chicks was characterized by gasping and listlessness with high mortality rates of 40–90%.[17] Leland David Bushnell and Carl Alfred Brandly isolated the virus that caused the infection in 1933.[18] The virus was then known as infectious bronchitis virus (IBV). Charles D. Hudson and Fred Robert Beaudette cultivated the virus for the first time in 1937.[19] The specimen came to be known as the Beaudette strain. In the late 1940s, two more animal coronaviruses, JHM that causes brain disease (murine encephalitis) and mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) that causes hepatitis in mice were discovered.[20] It was not realized at the time that these three different viruses were related.[21][13]

Human coronaviruses were discovered in the 1960s[22][23] using two different methods in the United Kingdom and the United States.[24] E.C. Kendall, Malcolm Bynoe, and David Tyrrell working at the Common Cold Unit of the British Medical Research Council collected a unique common cold virus designated B814 in 1961.[25][26][27] The virus could not be cultivated using standard techniques which had successfully cultivated rhinoviruses, adenoviruses and other known common cold viruses. In 1965, Tyrrell and Bynoe successfully cultivated the novel virus by serially passing it through organ culture of human embryonic trachea.[28] The new cultivating method was introduced to the lab by Bertil Hoorn.[29] The isolated virus when intranasally inoculated into volunteers caused a cold and was inactivated by ether which indicated it had a lipid envelope.[25][30] Dorothy Hamre[31] and John Procknow at the University of Chicago isolated a novel cold from medical students in 1962. They isolated and grew the virus in kidney tissue culture, designating it 229E. The novel virus caused a cold in volunteers and, like B814, was inactivated by ether.[32]

Scottish virologist June Almeida at St. Thomas Hospital in London, collaborating with Tyrrell, compared the structures of IBV, B814 and 229E in 1967.[33][34] Using electron microscopy the three viruses were shown to be morphologically related by their general shape and distinctive club-like spikes.[35] A research group at the National Institute of Health the same year was able to isolate another member of this new group of viruses using organ culture and named one of the samples OC43 (OC for organ culture).[36] Like B814, 229E, and IBV, the novel cold virus OC43 had distinctive club-like spikes when observed with the electron microscope.[37][38]

The IBV-like novel cold viruses were soon shown to be also morphologically related to the mouse hepatitis virus.[20] This new group of viruses were named coronaviruses after their distinctive morphological appearance.[8] Human coronavirus 229E and human coronavirus OC43 continued to be studied in subsequent decades.[39][40] The coronavirus strain B814 was lost. It is not known which present human coronavirus it was.[41] Other human coronaviruses have since been identified, including SARS-CoV in 2003, HCoV NL63 in 2003, HCoV HKU1 in 2004, MERS-CoV in 2013, and SARS-CoV-2 in 2019.[42] There have also been a large number of animal coronaviruses identified since the 1960s.[43]

Microbiology

Structure

Coronaviruses are large, roughly spherical particles with unique surface projections.[44] Their size is highly variable with average diameters of 80 to 120 nm. Extreme sizes are known from 50 to 200 nm in diameter.[45] The total molecular mass is on average 40,000 kDa. They are enclosed in an envelope embedded with a number of protein molecules.[46] The lipid bilayer envelope, membrane proteins, and nucleocapsid protect the virus when it is outside the host cell.[47]

The viral envelope is made up of a lipid bilayer in which the membrane (M), envelope (E) and spike (S) structural proteins are anchored.[48] The molar ratio of E:S:M in the lipid bilayer is approximately 1:20:300.[49] The E and M protein are the structural proteins that combined with the lipid bilayer to shape the viral envelope and maintain its size.[50] S proteins are needed for interaction with the host cells. But human coronavirus NL63 is peculiar in that its M protein has the binding site for the host cell, and not its S protein.[51] The diameter of the envelope is 85 nm. The envelope of the virus in electron micrographs appears as a distinct pair of electron-dense shells (shells that are relatively opaque to the electron beam used to scan the virus particle).[52][50]

The M protein is the main structural protein of the envelope that provides the overall shape and is a type III membrane protein. It consists of 218 to 263 amino acid residues and forms a layer 7.8 nm thick.[46] It has three domains, a short N-terminal ectodomain, a triple-spanning transmembrane domain, and a C-terminal endodomain. The C-terminal domain forms a matrix-like lattice that adds to the extra-thickness of the envelope. Different species can have either N- or O-linked glycans in their protein amino-terminal domain. The M protein is crucial during the assembly, budding, envelope formation, and pathogenesis stages of the virus lifecycle.[53]

The E proteins are minor structural proteins and highly variable in different species.[45] There are only about 20 copies of the E protein molecule in a coronavirus particle.[49] They are 8.4 to 12 kDa in size and are composed of 76 to 109 amino acids.[45] They are integral proteins (i.e. embedded in the lipid layer) and have two domains namely a transmembrane domain and an extramembrane C-terminal domain. They are almost fully α-helical, with a single α-helical transmembrane domain, and form pentameric (five-molecular) ion channels in the lipid bilayer. They are responsible for virion assembly, intracellular trafficking and morphogenesis (budding).[46]

The spikes are the most distinguishing feature of coronaviruses and are responsible for the corona- or halo-like surface. On average a coronavirus particle has 74 surface spikes.[54] Each spike is about 20 nm long and is composed of a trimer of the S protein. The S protein is in turn composed of an S1 and S2 subunit. The homotrimeric S protein is a class I fusion protein which mediates the receptor binding and membrane fusion between the virus and host cell. The S1 subunit forms the head of the spike and has the receptor-binding domain (RBD). The S2 subunit forms the stem which anchors the spike in the viral envelope and on protease activation enables fusion. The two subunits remain noncovalently linked as they are exposed on the viral surface until they attach to the host cell membrane.[46] In a functionally active state, three S1 are attached to two S2 subunits. The subunit complex is split into individual subunits when the virus binds and fuses with the host cell under the action of proteases such as cathepsin family and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) of the host cell.[55]

S1 proteins are the most critical components in terms of infection. They are also the most variable components as they are responsible for host cell specificity. They possess two major domains named N-terminal domain (S1-NTD) and C-terminal domain (S1-CTD), both of which serve as the receptor-binding domains. The NTDs recognize and bind sugars on the surface of the host cell. An exception is the MHV NTD that binds to a protein receptor carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1). S1-CTDs are responsible for recognizing different protein receptors such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), aminopeptidase N (APN), and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4).[46]

A subset of coronaviruses (specifically the members of betacoronavirus subgroup A) also has a shorter spike-like surface protein called hemagglutinin esterase (HE).[43] The HE proteins occur as homodimers composed of about 400 amino acid residues and are 40 to 50 kDa in size. They appear as tiny surface projections of 5 to 7 nm long embedded in between the spikes. They help in the attachment to and detachment from the host cell.[56]

Inside the envelope, there is the nucleocapsid, which is formed from multiple copies of the nucleocapsid (N) protein, which are bound to the positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome in a continuous beads-on-a-string type conformation.[50][57] N protein is a phosphoprotein of 43 to 50 kDa in size, and is divided into three conserved domains. The majority of the protein is made up of domains 1 and 2, which are typically rich in arginines and lysines. Domain 3 has a short carboxy terminal end and has a net negative charge due to excess of acidic over basic amino acid residues.[45]

Genome

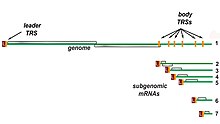

Coronaviruses contain a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The genome size for coronaviruses ranges from 26.4 to 31.7 kilobases.[7] The genome size is one of the largest among RNA viruses. The genome has a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail.[50]

The genome organization for a coronavirus is 5′-leader-UTR-replicase (ORF1ab)-spike (S)-envelope (E)-membrane (M)-nucleocapsid (N)-3′UTR-poly (A) tail. The open reading frames 1a and 1b, which occupy the first two-thirds of the genome, encode the replicase polyprotein (pp1ab). The replicase polyprotein self cleaves to form 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1–nsp16).[50]

The later reading frames encode the four major structural proteins: spike, envelope, membrane, and nucleocapsid.[58] Interspersed between these reading frames are the reading frames for the accessory proteins. The number of accessory proteins and their function is unique depending on the specific coronavirus.[50]

Replication cycle

Cell entry

Infection begins when the viral spike protein attaches to its complementary host cell receptor. After attachment, a protease of the host cell cleaves and activates the receptor-attached spike protein. Depending on the host cell protease available, cleavage and activation allows the virus to enter the host cell by endocytosis or direct fusion of the viral envelope with the host membrane.[59]

Genome translation

On entry into the host cell, the virus particle is uncoated, and its genome enters the cell cytoplasm. The coronavirus RNA genome has a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail, which allows it to act like a messenger RNA and be directly translated by the host cell's ribosomes. The host ribosomes translate the initial overlapping open reading frames ORF1a and ORF1b of the virus genome into two large overlapping polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab.[50]

The larger polyprotein pp1ab is a result of a -1 ribosomal frameshift caused by a slippery sequence (UUUAAAC) and a downstream RNA pseudoknot at the end of open reading frame ORF1a.[60] The ribosomal frameshift allows for the continuous translation of ORF1a followed by ORF1b.[50]

The polyproteins have their own proteases, PLpro (nsp3) and 3CLpro (nsp5), which cleave the polyproteins at different specific sites. The cleavage of polyprotein pp1ab yields 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1 to nsp16). Product proteins include various replication proteins such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (nsp12), RNA helicase (nsp13), and exoribonuclease (nsp14).[50]

Replicase-transcriptase

A number of the nonstructural proteins coalesce to form a multi-protein replicase-transcriptase complex. The main replicase-transcriptase protein is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). It is directly involved in the replication and transcription of RNA from an RNA strand. The other nonstructural proteins in the complex assist in the replication and transcription process. The exoribonuclease nonstructural protein, for instance, provides extra fidelity to replication by providing a proofreading function which the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase lacks.[61]

Replication – One of the main functions of the complex is to replicate the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis of negative-sense genomic RNA from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This is followed by the replication of positive-sense genomic RNA from the negative-sense genomic RNA.[50]

Transcription – The other important function of the complex is to transcribe the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis of negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This process is followed by the transcription of these negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules to their corresponding positive-sense mRNAs.[50] The subgenomic mRNAs form a "nested set" which have a common 5'-head and partially duplicate 3'-end.[62]

Recombination – The replicase-transcriptase complex is also capable of genetic recombination when at least two viral genomes are present in the same infected cell.[62] RNA recombination appears to be a major driving force in determining genetic variability within a coronavirus species, the capability of a coronavirus species to jump from one host to another and, infrequently, in determining the emergence of novel coronaviruses.[63] The exact mechanism of recombination in coronaviruses is unclear, but likely involves template switching during genome replication.[63]

Assembly and release

The replicated positive-sense genomic RNA becomes the genome of the progeny viruses. The mRNAs are gene transcripts of the last third of the virus genome after the initial overlapping reading frame. These mRNAs are translated by the host's ribosomes into the structural proteins and many accessory proteins.[50] RNA translation occurs inside the endoplasmic reticulum. The viral structural proteins S, E, and M move along the secretory pathway into the Golgi intermediate compartment. There, the M proteins direct most protein-protein interactions required for the assembly of viruses following its binding to the nucleocapsid. Progeny viruses are then released from the host cell by exocytosis through secretory vesicles. Once released the viruses can infect other host cells.[64]

Transmission

Infected carriers are able to shed viruses into the environment. The interaction of the coronavirus spike protein with its complementary cell receptor is central in determining the tissue tropism, infectivity, and species range of the released virus.[65][66] Coronaviruses mainly target epithelial cells.[43] They are transmitted from one host to another host, depending on the coronavirus species, by either an aerosol, fomite, or fecal-oral route.[67]

Human coronaviruses infect the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, while animal coronaviruses generally infect the epithelial cells of the digestive tract.[43] SARS coronavirus, for example, infects the human epithelial cells of the lungs via an aerosol route[68] by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.[69] Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) infects the pig epithelial cells of the digestive tract via a fecal-oral route[67] by binding to the alanine aminopeptidase (APN) receptor.[50]

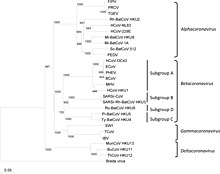

Classification

Coronaviruses form the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae,[3][4][5] which is one of two sub-families in the family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales, and realm Riboviria.[43][70] They are divided into the four genera: Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus. Alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses infect mammals, while gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses primarily infect birds.[71][72]

- Genus: Alphacoronavirus;[67]

- Genus Betacoronavirus;[68]

- Species: Betacoronavirus 1 (Bovine Coronavirus, Human coronavirus OC43), Hedgehog coronavirus 1, Human coronavirus HKU1, Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus, Murine coronavirus, Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5, Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9, Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2), Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4

- Genus Gammacoronavirus;[19]

- Genus Deltacoronavirus

Origin

The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all coronaviruses is estimated to have existed as recently as 8000 BCE, although some models place the common ancestor as far back as 55 million years or more, implying long term coevolution with bat and avian species.[73] The most recent common ancestor of the alphacoronavirus line has been placed at about 2400 BCE, of the betacoronavirus line at 3300 BCE, of the gammacoronavirus line at 2800 BCE, and the deltacoronavirus line at about 3000 BCE. Bats and birds, as warm-blooded flying vertebrates, are an ideal natural reservoir for the coronavirus gene pool (with bats the reservoir for alphacoronaviruses and betacoronavirus – and birds the reservoir for gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses). The large number and global range of bat and avian species that host viruses have enabled extensive evolution and dissemination of coronaviruses.[74]

Many human coronaviruses have their origin in bats.[75] The human coronavirus NL63 shared a common ancestor with a bat coronavirus (ARCoV.2) between 1190 and 1449 CE.[76] The human coronavirus 229E shared a common ancestor with a bat coronavirus (GhanaGrp1 Bt CoV) between 1686 and 1800 CE.[77] More recently, alpaca coronavirus and human coronavirus 229E diverged sometime before 1960.[78] MERS-CoV emerged in humans from bats through the intermediate host of camels.[79] MERS-CoV, although related to several bat coronavirus species, appears to have diverged from these several centuries ago.[80] The most closely related bat coronavirus and SARS-CoV diverged in 1986.[81] The ancestors of SARS-CoV first infected leaf-nose bats of the genus Hipposideridae; subsequently, they spread to horseshoe bats in the species Rhinolophidae, then to Asian palm civets, and finally to humans.[82][83]

Unlike other betacoronaviruses, bovine coronavirus of the species Betacoronavirus 1 and subgenus Embecovirus is thought to have originated in rodents and not in bats.[75][84] In the 1790s, equine coronavirus diverged from the bovine coronavirus after a cross-species jump.[85] Later in the 1890s, human coronavirus OC43 diverged from bovine coronavirus after another cross-species spillover event.[86][85] It is speculated that the flu pandemic of 1890 may have been caused by this spillover event, and not by the influenza virus, because of the related timing, neurological symptoms, and unknown causative agent of the pandemic.[87] Besides causing respiratory infections, human coronavirus OC43 is also suspected of playing a role in neurological diseases.[88] In the 1950s, the human coronavirus OC43 began to diverge into its present genotypes.[89] Phylogenetically, mouse hepatitis virus (Murine coronavirus), which infects the mouse's liver and central nervous system,[90] is related to human coronavirus OC43 and bovine coronavirus. Human coronavirus HKU1, like the aforementioned viruses, also has its origins in rodents.[75]

Infection in humans

Coronaviruses vary significantly in risk factor. Some can kill more than 30% of those infected, such as MERS-CoV, and some are relatively harmless, such as the common cold.[50] Coronaviruses can cause colds with major symptoms, such as fever, and a sore throat from swollen adenoids.[91] Coronaviruses can cause pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia) and bronchitis (either direct viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis).[92] The human coronavirus discovered in 2003, SARS-CoV, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), has a unique pathogenesis because it causes both upper and lower respiratory tract infections.[92]

Six species of human coronaviruses are known, with one species subdivided into two different strains, making seven strains of human coronaviruses altogether.

Four human coronaviruses produce symptoms that are generally mild, even though it is contended they might have been more aggressive in the past:[93]

- Human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43), β-CoV

- Human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1), β-CoV

- Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), α-CoV

- Human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63), α-CoV

Three human coronaviruses produce potentially severe symptoms:

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), β-CoV (identified in 2003)

- Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV), β-CoV (identified in 2012)

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), β-CoV (identified in 2019)

These cause the diseases commonly called SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 respectively.

Common cold

Although the common cold is usually caused by rhinoviruses,[94] in about 15% of cases the cause is a coronavirus.[95] The human coronaviruses HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-NL63 continually circulate in the human population in adults and children worldwide and produce the generally mild symptoms of the common cold.[96] The four mild coronaviruses have a seasonal incidence occurring in the winter months in temperate climates.[97][98] There is no preponderance in any season in tropical climates.[99]

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

| MERS-CoV | SARS-CoV | SARS-CoV-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | MERS | SARS | COVID-19 |

| Outbreaks | 2012, 2015, 2018 |

2002–2004 | 2019–2021 pandemic |

| Epidemiology | |||

| Date of first identified case |

June 2012 |

November 2002 |

December 2019[100] |

| Location of first identified case |

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia |

Shunde, China |

Wuhan, China |

| Age average | 56 | 44[101][a] | 56[102] |

| Sex ratio (M:F) | 3.3:1 | 0.8:1[103] | 1.6:1[102] |

| Confirmed cases | 2494 | 8096[104] | 175,668,875[105][b] |

| Deaths | 858 | 774[104] | 3,795,554[105][b] |

| Case fatality rate | 37% | 9.2% | 2.2%[105] |

| Symptoms | |||

| Fever | 98% | 99–100% | 87.9%[106] |

| Dry cough | 47% | 29–75% | 67.7%[106] |

| Dyspnea | 72% | 40–42% | 18.6%[106] |

| Diarrhea | 26% | 20–25% | 3.7%[106] |

| Sore throat | 21% | 13–25% | 13.9%[106] |

| Ventilatory use | 24.5%[107] | 14–20% | 4.1%[108] |

| Notes | |||

In 2003, following the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) which had begun the prior year in Asia, and secondary cases elsewhere in the world, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a press release stating that a novel coronavirus identified by several laboratories was the causative agent for SARS. The virus was officially named the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV). More than 8,000 people from 29 different countries and territories were infected, and at least 774 died.[109][69]

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)

In September 2012, a new type of coronavirus was identified, initially called Novel Coronavirus 2012, and now officially named Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).[110][111] The World Health Organization issued a global alert soon after.[112] The WHO update on 28 September 2012 said the virus did not seem to pass easily from person to person.[113] However, on 12 May 2013, a case of human-to-human transmission in France was confirmed by the French Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.[114] In addition, cases of human-to-human transmission were reported by the Ministry of Health in Tunisia. Two confirmed cases involved people who seemed to have caught the disease from their late father, who became ill after a visit to Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Despite this, it appears the virus had trouble spreading from human to human, as most individuals who are infected do not transmit the virus.[115] By 30 October 2013, there were 124 cases and 52 deaths in Saudi Arabia.[116]

After the Dutch Erasmus Medical Centre sequenced the virus, the virus was given a new name, Human Coronavirus—Erasmus Medical Centre (HCoV-EMC). The final name for the virus is Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The only U.S. cases (both survived) were recorded in May 2014.[117]

In May 2015, an outbreak of MERS-CoV occurred in the Republic of Korea, when a man who had traveled to the Middle East, visited four hospitals in the Seoul area to treat his illness. This caused one of the largest outbreaks of MERS-CoV outside the Middle East.[118] As of December 2019, 2,468 cases of MERS-CoV infection had been confirmed by laboratory tests, 851 of which were fatal, a mortality rate of approximately 34.5%.[119]

In December 2019, a pneumonia outbreak was reported in Wuhan, China.[120] On 31 December 2019, the outbreak was traced to a novel strain of coronavirus,[121] which was given the interim name 2019-nCoV by the World Health Organization (WHO),[122][123][124] later renamed SARS-CoV-2 by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.

As of 13 June 2021, there have been at least 3,795,554[105] confirmed deaths and more than 175,668,875[105] confirmed cases in the COVID-19 pandemic. The Wuhan strain has been identified as a new strain of Betacoronavirus from group 2B with approximately 70% genetic similarity to the SARS-CoV.[125] The virus has a 96% similarity to a bat coronavirus, so it is widely suspected to originate from bats as well.[126][127]

During a surveillance study of archived samples of Malaysian viral pneumonia patients, virologists identified a strain of canine coronavirus which has infected humans in 2018.

Infection in animals

Coronaviruses have been recognized as causing pathological conditions in veterinary medicine since the 1930s.[20] They infect a range of animals including swine, cattle, horses, camels, cats, dogs, rodents, birds and bats.[128] The majority of animal related coronaviruses infect the intestinal tract and are transmitted by a fecal-oral route.[129] Significant research efforts have been focused on elucidating the viral pathogenesis of these animal coronaviruses, especially by virologists interested in veterinary and zoonotic diseases.[130]

Farm animals

Coronaviruses infect domesticated birds.[131] Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), a type of coronavirus, causes avian infectious bronchitis.[132] The virus is of concern to the poultry industry because of the high mortality from infection, its rapid spread, and its effect on production.[128] The virus affects both meat production and egg production and causes substantial economic loss.[133] In chickens, infectious bronchitis virus targets not only the respiratory tract but also the urogenital tract. The virus can spread to different organs throughout the chicken.[132] The virus is transmitted by aerosol and food contaminated by feces. Different vaccines against IBV exist and have helped to limit the spread of the virus and its variants.[128] Infectious bronchitis virus is one of a number of strains of the species Avian coronavirus.[134] Another strain of avian coronavirus is turkey coronavirus (TCV) which causes enteritis in turkeys.[128]

Coronaviruses also affect other branches of animal husbandry such as pig farming and the cattle raising.[128] Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus (SADS-CoV), which is related to bat coronavirus HKU2, causes diarrhea in pigs.[135] Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is a coronavirus that has recently emerged and similarly causes diarrhea in pigs.[136] Transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), which is a member of the species Alphacoronavirus 1,[137] is another coronavirus that causes diarrhea in young pigs.[138][139] In the cattle industry bovine coronavirus (BCV), which is a member of the species Betacoronavirus 1 and related to HCoV-OC43,[140] is responsible for severe profuse enteritis in young calves.[128]

Domestic pets

Coronaviruses infect domestic pets such as cats, dogs, and ferrets.[131] There are two forms of feline coronavirus which are both members of the species Alphacoronavirus 1.[137] Feline enteric coronavirus is a pathogen of minor clinical significance, but spontaneous mutation of this virus can result in feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a disease with high mortality.[128] There are two different coronaviruses that infect dogs. Canine coronavirus (CCoV), which is a member of the species Alphacoronavirus 1,[137] causes mild gastrointestinal disease.[128] Canine respiratory coronavirus (CRCoV), which is a member of the species Betacoronavirus 1 and related to HCoV-OC43,[140] cause respiratory disease.[128] Similarly, there are two types of coronavirus that infect ferrets.[141] Ferret enteric coronavirus causes a gastrointestinal syndrome known as epizootic catarrhal enteritis (ECE), and a more lethal systemic version of the virus (like FIP in cats) known as ferret systemic coronavirus (FSC).[142][143]

Laboratory animals

Coronaviruses infect laboratory animals.[128] Mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), which is a member of the species Murine coronavirus,[144] causes an epidemic murine illness with high mortality, especially among colonies of laboratory mice.[145] Prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV, MHV was the best-studied coronavirus both in vivo and in vitro as well as at the molecular level. Some strains of MHV cause a progressive demyelinating encephalitis in mice which has been used as a murine model for multiple sclerosis.[130] Sialodacryoadenitis virus (SDAV), which is a strain of the species Murine coronavirus,[144] is highly infectious coronavirus of laboratory rats, which can be transmitted between individuals by direct contact and indirectly by aerosol. Rabbit enteric coronavirus causes acute gastrointestinal disease and diarrhea in young European rabbits.[128] Mortality rates are high.[146]

Prevention and treatment

A number of vaccines using different methods have been developed against human coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.[147][148] Antiviral targets against human coronaviruses have also been identified such as viral proteases, polymerases, and entry proteins. Drugs are in development which target these proteins and the different steps of viral replication.[149][148]

Vaccines are available for animal coronaviruses IBV, TGEV, and Canine CoV, although their effectiveness is limited. In the case of outbreaks of highly contagious animal coronaviruses, such as PEDV, measures such as destruction of entire herds of pigs may be used to prevent transmission to other herds.[50]

See also

References

- ^ "Virus Taxonomy: 2018b Release". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). March 2019. Archived from the original on 2018-03-04. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ Giaimo C (2020-04-01). "The Spiky Blob Seen Around the World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2020-04-02. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ a b "2017.012-015S" (xlsx). International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). October 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-05-14. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ a b c Fan Y, Zhao K, Shi ZL, Zhou P (March 2019). "Bat Coronaviruses in China". Viruses. 11 (3): 210. doi:10.3390/v11030210. PMC 6466186. PMID 30832341.

- ^ Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, Steinbach WJ, Hotez PJ (2017). Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. PT6615. ISBN 978-0-323-39281-5.

- ^ a b Woo PC, Huang Y, Lau SK, Yuen KY (August 2010). "Coronavirus genomics and bioinformatics analysis". Viruses. 2 (8): 1804–20. doi:10.3390/v2081803. PMC 3185738. PMID 21994708.

Coronaviruses possess the largest genomes [26.4 kb (ThCoV HKU12) to 31.7 kb (SW1)] among all known RNA viruses (Figure 1) [2,13,16].

- ^ a b c d Almeida JD, Berry DM, Cunningham CH, Hamre D, Hofstad MS, Mallucci L, McIntosh K, Tyrrell DA (November 1968). "Virology: Coronaviruses". Nature. 220 (5168): 650. Bibcode:1968Natur.220..650.. doi:10.1038/220650b0.

[T]here is also a characteristic "fringe" of projections 200 A long, which are rounded or petal shaped ... This appearance, recalling the solar corona, is shared by mouse hepatitis virus and several viruses recently recovered from man, namely strain B814, 229E and several others.

- ^ "Definition of Coronavirus by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2020-03-23. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- ^ "Definition of Corona by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2020-03-24. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- ^ a b Tyrrell DA, Fielder M (2002). Cold Wars: The Fight Against the Common Cold. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-263285-2.

We looked more closely at the appearance of the new viruses and noticed that they had a kind of halo surrounding them. Recourse to a dictionary produced the Latin equivalent, corona, and so the name coronavirus was born.

- ^ Sturman LS, Holmes KV (1983-01-01). Lauffer MA, Maramorosch K (eds.). "The molecular biology of coronaviruses". Advances in Virus Research. 28: 35–112. doi:10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60721-6. ISBN 9780120398287. PMC 7131312. PMID 6362367.

[T]hese viruses displayed a characteristic fringe of large, distinctive, petal-shaped peplomers or spikes which resembled a crown, like the corona spinarum in religious art; hence the name coronaviruses.

- ^ a b Lalchhandama K (2020). "The chronicles of coronaviruses: the bronchitis, the hepatitis and the common cold". Science Vision. 20 (1): 43–53. doi:10.33493/scivis.20.01.04.

- ^ Carstens EB (2010). "Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2009)". Archives of Virology. 155 (1): 133–46. doi:10.1007/s00705-009-0547-x. PMC 7086975. PMID 19960211.

- ^ "International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV)". talk.ictvonline.org. Retrieved 2020-09-14.

- ^ Estola T (1970). "Coronaviruses, a New Group of Animal RNA Viruses". Avian Diseases. 14 (2): 330–336. doi:10.2307/1588476. ISSN 0005-2086. JSTOR 1588476. PMID 4316767.

- ^ Fabricant J (1998). "The Early History of Infectious Bronchitis". Avian Diseases. 42 (4): 648–650. doi:10.2307/1592697. ISSN 0005-2086. JSTOR 1592697. PMID 9876830.

- ^ Bushnell LD, Brandly CA (1933). "Laryngotracheitis in chicks". Poultry Science. 12 (1): 55–60. doi:10.3382/ps.0120055.

- ^ a b Decaro N (2011). "Gammacoronavirus". In Tidona C, Darai G (eds.). Gammacoronavirus‡: Coronaviridae. The Springer Index of Viruses. Springer. pp. 403–413. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-95919-1_58. ISBN 978-0-387-95919-1. PMC 7176155.

- ^ a b c McIntosh K (1974). "Coronaviruses: A Comparative Review". In Arber W, Haas R, Henle W, Hofschneider PH, Jerne NK, Koldovský P, Koprowski H, Maaløe O, Rott R (eds.). Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology / Ergebnisse der Mikrobiologie und Immunitätsforschung. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology / Ergebnisse der Mikrobiologie und Immunitätsforschung. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. p. 87. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-65775-7_3. ISBN 978-3-642-65775-7.

- ^ "Il était une fois les coronavirus". Réalités Biomédicales (in French). 2020-03-27. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ Kahn JS, McIntosh K (November 2005). "History and recent advances in coronavirus discovery". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 24 (11 Suppl): S223–7, discussion S226. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000188166.17324.60. PMID 16378050.

- ^ Mahase E (April 2020). "The BMJ in 1965". BMJ. 369: m1547. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1547. PMID 32299810.

- ^ Monto AS (1984). "Coronaviruses". In Evans AS (ed.). Viral Infections of Humans. Viral Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. Springer US. pp. 151–165. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-4727-9_7. ISBN 978-1-4684-4727-9.

- ^ a b Kendall EJ, Bynoe ML, Tyrrell DA (July 1962). "Virus isolations from common colds occurring in a residential school". British Medical Journal. 2 (5297): 82–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5297.82. PMC 1925312. PMID 14455113.

- ^ Richmond C (2005-06-18). "David Tyrrell". BMJ : British Medical Journal. 330 (7505): 1451. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7505.1451. PMC 558394.

- ^ "Obituary Notices: Malcom Byone". British Medical Journal. 2 (5660): 827–829. 1969-06-28. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5660.827. S2CID 220187042.

- ^ Tyrrell DA, Bynoe ML (June 1965). "Cultivation of a Novel Type of Common-Cold Virus in Organ Cultures". British Medical Journal. 1 (5448): 1467–70. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5448.1467. PMC 2166670. PMID 14288084.

- ^ Tyrrell DA, Fielder M (2002). Cold Wars: The Fight Against the Common Cold. Oxford University Press. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-0-19-263285-2.

- ^ Hagan WA, Bruner DW, Gillespie JH, Timoney JF, Scott FW, Barlough JE (1988). Hagan and Bruner's Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals: With Reference to Etiology, Epizootiology, Pathogenesis, Immunity, Diagnosis, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility. Cornell University Press. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-8014-1896-9.

- ^ Knapp, Alex. "The Secret History Of The First Coronavirus". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ Hamre D, Procknow JJ (January 1966). "A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 121 (1): 190–3. doi:10.3181/00379727-121-30734. PMID 4285768. S2CID 1314901.

- ^ "The woman who discovered the first coronavirus".

- ^ Almeida J (2008-06-26). "June Almeida (née Hart)". BMJ. 336 (7659): 1511.1–1511. doi:10.1136/bmj.a434. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 2440895.

- ^ Almeida JD, Tyrrell DA (April 1967). "The morphology of three previously uncharacterized human respiratory viruses that grow in organ culture". The Journal of General Virology. 1 (2): 175–8. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-1-2-175. PMID 4293939.

- ^ McIntosh K, Becker WB, Chanock RM (December 1967). "Growth in suckling-mouse brain of "IBV-like" viruses from patients with upper respiratory tract disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 58 (6): 2268–73. Bibcode:1967PNAS...58.2268M. doi:10.1073/pnas.58.6.2268. PMC 223830. PMID 4298953.

- ^ McIntosh K, Dees JH, Becker WB, Kapikian AZ, Chanock RM (April 1967). "Recovery in tracheal organ cultures of novel viruses from patients with respiratory disease". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 57 (4): 933–40. Bibcode:1967PNAS...57..933M. doi:10.1073/pnas.57.4.933. PMC 224637. PMID 5231356.

- ^ Times, Harold M. Schmeck Jr Special To the New York (1967-05-05). "Six Newly Discovered Viruses May Explain Cold; Strains Are Similar to Germ That Causes a Bronchial Infection in Chickens Believed to Be New Group". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- ^ Myint SH (1995). "Human Coronavirus Infections". In Siddell SG (ed.). The Coronaviridae. The Viruses. Springer US. pp. 389–401. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1531-3_18. ISBN 978-1-4899-1531-3.

- ^ Geller C, Varbanov M, Duval RE (November 2012). "Human coronaviruses: insights into environmental resistance and its influence on the development of new antiseptic strategies". Viruses. 4 (11): 3044–68. doi:10.3390/v4113044. PMC 3509683. PMID 23202515.

- ^ Corman VM, Jores J, Meyer B, Younan M, Liljander A, Said MY, et al. (August 2014). "Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, Kenya, 1992-2013". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (8): 1319–22. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-7448-8_10. ISBN 978-1-4899-7447-1. PMC 7122465. PMID 25075637.

The other OC strains and B814 that could not be adapted to mouse brain resisted adaptation to cell culture as well; these distinct viruses have since been lost and may actually have been rediscovered recently.

- ^ Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. (February 2020). "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 727–733. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. PMC 7092803. PMID 31978945.

- ^ a b c d e de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric R, Enjuanes L, Gorbalenya AE, Holmes KV, Perlman S, Poon L, Rottier PJ, Talbot PJ, Woo PC, Ziebuhr J (2011). "Family Coronaviridae". In King AM, Lefkowitz E, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, International Union of Microbiological Societies. Virology Division (eds.). Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 806–28. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-384684-6.00068-9. ISBN 978-0-12-384684-6. S2CID 212719285.

- ^ Goldsmith CS, Tatti KM, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Comer JA, Lee WW, et al. (February 2004). "Ultrastructural characterization of SARS coronavirus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (2): 320–6. doi:10.3201/eid1002.030913. PMC 3322934. PMID 15030705.

Virions acquired an envelope by budding into the cisternae and formed mostly spherical, sometimes pleomorphic, particles that averaged 78 nm in diameter (Figure 1A).

- ^ a b c d Masters PS (2006). "The molecular biology of coronaviruses". Advances in Virus Research. 66: 193–292. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. ISBN 9780120398690. PMC 7112330. PMID 16877062.

- ^ a b c d e Lalchhandama K (2020). "The chronicles of coronaviruses: the electron microscope, the doughnut, and the spike". Science Vision. 20 (2): 78–92. doi:10.33493/scivis.20.02.03.

- ^ Neuman BW, Kiss G, Kunding AH, Bhella D, Baksh MF, Connelly S, et al. (April 2011). "A structural analysis of M protein in coronavirus assembly and morphology". Journal of Structural Biology. 174 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.021. PMC 4486061. PMID 21130884.

See Figure 10.

- ^ Lai MM, Cavanagh D (1997). "The molecular biology of coronaviruses". Advances in Virus Research. 48: 1–100. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. ISBN 9780120398485. PMC 7130985. PMID 9233431.

- ^ a b Godet M, L'Haridon R, Vautherot JF, Laude H (1992). "TGEV corona virus ORF4 encodes a membrane protein that is incorporated into virions". Virology. 188 (2): 666–75. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(92)90521-p. PMC 7131960. PMID 1316677.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Fehr AR, Perlman S (2015). "Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis". In Maier HJ, Bickerton E, Britton P (eds.). Coronaviruses. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1282. Springer. pp. 1–23. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. ISBN 978-1-4939-2438-7. PMC 4369385. PMID 25720466.

See section: Virion Structure.

- ^ Naskalska A, Dabrowska A, Szczepanski A, Milewska A, Jasik KP, Pyrc K (October 2019). "Membrane Protein of Human Coronavirus NL63 Is Responsible for Interaction with the Adhesion Receptor". Journal of Virology. 93 (19). doi:10.1128/JVI.00355-19. PMC 6744225. PMID 31315999.

- ^ Neuman BW, Adair BD, Yoshioka C, Quispe JD, Orca G, Kuhn P, et al. (August 2006). "Supramolecular architecture of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus revealed by electron cryomicroscopy". Journal of Virology. 80 (16): 7918–28. doi:10.1128/JVI.00645-06. PMC 1563832. PMID 16873249.

Particle diameters ranged from 50 to 150 nm, excluding the spikes, with mean particle diameters of 82 to 94 nm; Also See Figure 1 for double shell.

- ^ Schoeman D, Fielding BC (May 2019). "Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge". Virology Journal. 16 (1): 69. doi:10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. PMC 6537279. PMID 31133031.

- ^ Neuman BW, Kiss G, Kunding AH, Bhella D, Baksh MF, Connelly S, et al. (April 2011). "A structural analysis of M protein in coronavirus assembly and morphology". Journal of Structural Biology. 174 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.021. PMC 4486061. PMID 21130884.

- ^ J Alsaadi EA, Jones IM (April 2019). "Membrane binding proteins of coronaviruses". Future Virology. 14 (4): 275–286. doi:10.2217/fvl-2018-0144. PMC 7079996. PMID 32201500.

- ^ Zeng Q, Langereis MA, van Vliet AL, Huizinga EG, de Groot RJ (July 2008). "Structure of coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase offers insight into corona and influenza virus evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (26): 9065–9. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9065Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800502105. PMC 2449365. PMID 18550812.

- ^ Chang CK, Hou MH, Chang CF, Hsiao CD, Huang TH (March 2014). "The SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid protein—forms and functions". Antiviral Research. 103: 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.12.009. PMC 7113676. PMID 24418573.

See Figure 4c.

- ^ Snijder EJ, Bredenbeek PJ, Dobbe JC, Thiel V, Ziebuhr J, Poon LL, et al. (August 2003). "Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage". Journal of Molecular Biology. 331 (5): 991–1004. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00865-9. PMC 7159028. PMID 12927536.

See Figure 1.

- ^ Simmons G, Zmora P, Gierer S, Heurich A, Pöhlmann S (December 2013). "Proteolytic activation of the SARS-coronavirus spike protein: cutting enzymes at the cutting edge of antiviral research". Antiviral Research. 100 (3): 605–14. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.09.028. PMC 3889862. PMID 24121034.

See Figure 2.

- ^ Masters PS (2006-01-01). "The molecular biology of coronaviruses". Advances in Virus Research. Academic Press. 66: 193–292. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. ISBN 9780120398690. PMC 7112330. PMID 16877062.

See Figure 8.

- ^ Sexton NR, Smith EC, Blanc H, Vignuzzi M, Peersen OB, Denison MR (August 2016). "Homology-Based Identification of a Mutation in the Coronavirus RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase That Confers Resistance to Multiple Mutagens". Journal of Virology. 90 (16): 7415–28. doi:10.1128/JVI.00080-16. PMC 4984655. PMID 27279608.

Finally, these results, combined with those from previous work (33, 44), suggest that CoVs encode at least three proteins involved in fidelity (nsp12-RdRp, nsp14-ExoN, and nsp10), supporting the assembly of a multiprotein replicase-fidelity complex, as described previously (38).

- ^ a b Payne S (2017-01-01). "Chapter 17 - Family Coronaviridae". Viruses. Academic Press. pp. 149–158. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803109-4.00017-9. ISBN 978-0-12-803109-4. S2CID 91572610.

- ^ a b Su S, Wong G, Shi W, Liu J, Lai AC, Zhou J, Liu W, Bi Y, Gao GF (June 2016). "Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses". Trends in Microbiology. 24 (6): 490–502. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. PMC 7125511. PMID 27012512.

- ^ Fehr AR, Perlman S (2015). "Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis". In Maier HJ, Bickerton E, Britton P (eds.). Coronaviruses. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1282. Springer. pp. 1–23. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. ISBN 978-1-4939-2438-7. PMC 4369385. PMID 25720466.

See section: Coronavirus Life Cycle—Assembly and Release

- ^ Masters PS (2006-01-01). "The molecular biology of coronaviruses". Advances in Virus Research. Academic Press. 66: 193–292. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. ISBN 978-0120398690. PMC 7112330. PMID 16877062.

Nevertheless, the interaction between S protein and receptor remains the principal, if not sole, determinant of coronavirus host species range and tissue tropism.

- ^ Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL (March 2019). "Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 17 (3): 181–92. doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. PMC 7097006. PMID 30531947.

Different SARS-CoV strains isolated from several hosts vary in their binding affinities for human ACE2 and consequently in their infectivity of human cells 76, 78 (Fig. 6b)

- ^ a b c Decaro N (2011). Tidona C, Darai G (eds.). Alphacoronavirus. The Springer Index of Viruses. Springer. pp. 371–383. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-95919-1_56. ISBN 978-0-387-95919-1. PMC 7176201.

- ^ a b Decaro N (2011). Tidona C, Darai G (eds.). Betacoronavirus. The Springer Index of Viruses. Springer. pp. 385–401. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-95919-1_57. ISBN 978-0-387-95919-1. PMC 7176184.

- ^ a b Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC (September 2005). "Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor". Science. 309 (5742): 1864–68. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.1864L. doi:10.1126/science.1116480. PMID 16166518. S2CID 12438123.

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2010-08-24). "ICTV Master Species List 2009—v10" (xls).

- ^ Wertheim JO, Chu DK, Peiris JS, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Poon LL (June 2013). "A case for the ancient origin of coronaviruses". Journal of Virology. 87 (12): 7039–45. doi:10.1128/JVI.03273-12. PMC 3676139. PMID 23596293.

Alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses are found exclusively in mammals, whereas gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses primarily infect birds.

- ^ Nextstrain, phylogenetic tree of Beta-CoV

- ^ Wertheim JO, Chu DK, Peiris JS, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Poon LL (June 2013). "A case for the ancient origin of coronaviruses". Journal of Virology. 87 (12): 7039–45. doi:10.1128/JVI.03273-12. PMC 3676139. PMID 23596293.

- ^ Woo PC, Lau SK, Lam CS, Lau CC, Tsang AK, Lau JH, et al. (April 2012). "Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus". Journal of Virology. 86 (7): 3995–4008. doi:10.1128/JVI.06540-11. PMC 3302495. PMID 22278237.

- ^ a b c Forni D, Cagliani R, Clerici M, Sironi M (January 2017). "Molecular Evolution of Human Coronavirus Genomes". Trends in Microbiology. 25 (1): 35–48. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.001. PMC 7111218. PMID 27743750.

Specifically, all HCoVs are thought to have a bat origin, with the exception of lineage A beta-CoVs, which may have reservoirs in rodents [2].

- ^ Huynh J, Li S, Yount B, Smith A, Sturges L, Olsen JC, et al. (December 2012). "Evidence supporting a zoonotic origin of human coronavirus strain NL63". Journal of Virology. 86 (23): 12816–25. doi:10.1128/JVI.00906-12. PMC 3497669. PMID 22993147.

If these predictions are correct, this observation suggests that HCoV-NL63 may have originated from bats between 1190 and 1449 CE.

- ^ Pfefferle S, Oppong S, Drexler JF, Gloza-Rausch F, Ipsen A, Seebens A, et al. (September 2009). "Distant relatives of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and close relatives of human coronavirus 229E in bats, Ghana". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (9): 1377–84. doi:10.3201/eid1509.090224. PMC 2819850. PMID 19788804.

The most recent common ancestor of hCoV-229E and GhanaBt-CoVGrp1 existed in ≈1686–1800 AD.

- ^ Crossley BM, Mock RE, Callison SA, Hietala SK (December 2012). "Identification and characterization of a novel alpaca respiratory coronavirus most closely related to the human coronavirus 229E". Viruses. 4 (12): 3689–700. doi:10.3390/v4123689. PMC 3528286. PMID 23235471.

- ^ Forni D, Cagliani R, Clerici M, Sironi M (January 2017). "Molecular Evolution of Human Coronavirus Genomes". Trends in Microbiology. 25 (1): 35–48. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.001. PMC 7111218. PMID 27743750.

- ^ Lau SK, Li KS, Tsang AK, Lam CS, Ahmed S, Chen H, et al. (August 2013). "Genetic characterization of Betacoronavirus lineage C viruses in bats reveals marked sequence divergence in the spike protein of pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 in Japanese pipistrelle: implications for the origin of the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus". Journal of Virology. 87 (15): 8638–50. doi:10.1128/JVI.01055-13. PMC 3719811. PMID 23720729.

- ^ Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ, Zhang JX, Peiris JS, Chen H, Guan Y (April 2007). "Evolutionary insights into the ecology of coronaviruses". Journal of Virology. 81 (8): 4012–20. doi:10.1128/jvi.02605-06. PMC 1866124. PMID 17267506.

- ^ Gouilh MA, Puechmaille SJ, Gonzalez JP, Teeling E, Kittayapong P, Manuguerra JC (October 2011). "SARS-Coronavirus ancestor's foot-prints in South-East Asian bat colonies and the refuge theory". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 11 (7): 1690–702. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2011.06.021. PMC 7106191. PMID 21763784.

- ^ Cui J, Han N, Streicker D, Li G, Tang X, Shi Z, et al. (October 2007). "Evolutionary relationships between bat coronaviruses and their hosts". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (10): 1526–32. doi:10.3201/eid1310.070448. PMC 2851503. PMID 18258002.

- ^ Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS, Tsang AK, Fan RY, Luk HK, et al. (March 2015). "Discovery of a novel coronavirus, China Rattus coronavirus HKU24, from Norway rats supports the murine origin of Betacoronavirus 1 and has implications for the ancestor of Betacoronavirus lineage A". Journal of Virology. 89 (6): 3076–92. doi:10.1128/JVI.02420-14. PMC 4337523. PMID 25552712.

- ^ a b Bidokhti MR, Tråvén M, Krishna NK, Munir M, Belák S, Alenius S, Cortey M (September 2013). "Evolutionary dynamics of bovine coronaviruses: natural selection pattern of the spike gene implies adaptive evolution of the strains". The Journal of General Virology. 94 (Pt 9): 2036–2049. doi:10.1099/vir.0.054940-0. PMID 23804565.

See Table 1

- ^ Vijgen L, Keyaerts E, Moës E, Thoelen I, Wollants E, Lemey P, et al. (February 2005). "Complete genomic sequence of human coronavirus OC43: molecular clock analysis suggests a relatively recent zoonotic coronavirus transmission event". Journal of Virology. 79 (3): 1595–604. doi:10.1128/jvi.79.3.1595-1604.2005. PMC 544107. PMID 15650185.

- ^ Vijgen L, Keyaerts E, Moës E, Thoelen I, Wollants E, Lemey P, et al. (February 2005). "Complete genomic sequence of human coronavirus OC43: molecular clock analysis suggests a relatively recent zoonotic coronavirus transmission event". Journal of Virology. 79 (3): 1595–604. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.3.1595-1604.2005. PMC 544107. PMID 15650185.

However, it is tempting to speculate about an alternative hypothesis, that the 1889-1890 pandemic may have been the result of interspecies transmission of bovine coronaviruses to humans, resulting in the subsequent emergence of HCoV-OC43.

- ^ Corman VM, Muth D, Niemeyer D, Drosten C (2018). "Hosts and Sources of Endemic Human Coronaviruses". Advances in Virus Research. 100: 163–188. doi:10.1016/bs.aivir.2018.01.001. ISBN 9780128152010. PMC 7112090. PMID 29551135.

- ^ Lau SK, Lee P, Tsang AK, Yip CC, Tse H, Lee RA, et al. (November 2011). "Molecular epidemiology of human coronavirus OC43 reveals evolution of different genotypes over time and recent emergence of a novel genotype due to natural recombination". Journal of Virology. 85 (21): 11325–37. doi:10.1128/JVI.05512-11. PMC 3194943. PMID 21849456.

- ^ Schaumburg CS, Held KS, Lane TE (May 2008). "Mouse hepatitis virus infection of the CNS: a model for defense, disease, and repair". Frontiers in Bioscience. 13 (13): 4393–406. doi:10.2741/3012. PMC 5025298. PMID 18508518.

- ^ Liu P, Shi L, Zhang W, He J, Liu C, Zhao C, et al. (November 2017). "Prevalence and genetic diversity analysis of human coronaviruses among cross-border children". Virology Journal. 14 (1): 230. doi:10.1186/s12985-017-0896-0. PMC 5700739. PMID 29166910.

- ^ a b Forgie S, Marrie TJ (February 2009). "Healthcare-associated atypical pneumonia". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 30 (1): 67–85. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1119811. PMID 19199189.

- ^ King, Anthony (2020-05-02). "An uncommon cold". New Scientist. 246 (3280): 32–35. Bibcode:2020NewSc.246...32K. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(20)30862-9. ISSN 0262-4079. PMC 7252012. PMID 32501321.

- ^ Cecil RL, Goldman L, Schafer AI (2012). Goldman's Cecil Medicine, Expert Consult Premium Edition (24 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2103–. ISBN 978-1-4377-1604-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-04.

- ^ Pelczar (2010). Microbiology: Application Based Approach. p. 656. ISBN 978-0-07-015147-5. Archived from the original on 2016-05-16.

- ^ Corman VM, Muth D, Niemeyer D, Drosten C (2018). "Hosts and Sources of Endemic Human Coronaviruses". Advances in Virus Research. 100: 163–188. doi:10.1016/bs.aivir.2018.01.001. ISBN 978-0-12-815201-0. PMC 7112090. PMID 29551135.

- ^ Charlton CL, Babady E, Ginocchio CC, Hatchette TF, Jerris RC, Li Y, et al. (January 2019). "Practical Guidance for Clinical Microbiology Laboratories: Viruses Causing Acute Respiratory Tract Infections". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 32 (1). doi:10.1128/CMR.00042-18. PMC 6302358. PMID 30541871.

See Figure 1.

- ^ Monto AS, DeJonge P, Callear AP, Bazzi LA, Capriola S, Malosh RE, et al. (April 2020). "Coronavirus occurrence and transmission over 8 years in the HIVE cohort of households in Michigan". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 222: 9–16. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa161. PMC 7184402. PMID 32246136.

- ^ Abdul-Rasool S, Fielding BC (May 2010). "Understanding Human Coronavirus HCoV-NL63". The Open Virology Journal. 4: 76–84. doi:10.2174/1874357901004010076. PMC 2918871. PMID 20700397.

- ^ Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF (February 2020). "A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern". Lancet. 395 (10223): 470–473. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. PMID 31986257.

- ^ Lau EH, Hsiung CA, Cowling BJ, Chen CH, Ho LM, Tsang T, et al. (March 2010). "A comparative epidemiologic analysis of SARS in Hong Kong, Beijing and Taiwan". BMC Infectious Diseases. 10: 50. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-50. PMC 2846944. PMID 20205928.

- ^ a b "Old age, sepsis tied to poor COVID-19 outcomes, death". CIDRAP, University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Karlberg J, Chong DS, Lai WY (February 2004). "Do men have a higher case fatality rate of severe acute respiratory syndrome than women do?". American Journal of Epidemiology. 159 (3): 229–31. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh056. PMID 14742282.

- ^ a b "Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003". World Health Organization. April 2004.

- ^ a b c d e "COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)". ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ a b c d e "Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (PDF). World Health Organization. February 2020.

- ^ Oh MD, Park WB, Park SW, Choe PG, Bang JH, Song KH, et al. (March 2018). "Middle East respiratory syndrome: what we learned from the 2015 outbreak in the Republic of Korea". The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 33 (2): 233–246. doi:10.3904/kjim.2018.031. PMC 5840604. PMID 29506344.

- ^ Ñamendys-Silva SA (March 2020). "Respiratory support for patients with COVID-19 infection". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30110-7. PMID 32145829.

- ^ Pasley, James. "How SARS terrified the world in 2003, infecting more than 8,000 people and killing 774". Business Insider. Retrieved 2020-11-08.

- ^ Doucleef M (2012-09-26). "Scientists Go Deep On Genes Of SARS-Like Virus". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2012-09-27. Retrieved 2012-09-27.

- ^ Falco M (2012-09-24). "New SARS-like virus poses medical mystery". CNN Health. Archived from the original on 2013-11-01. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ "New SARS-like virus found in Middle East". Al-Jazeera. 2012-09-24. Archived from the original on 2013-03-09. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ Kelland K (2012-09-28). "New virus not spreading easily between people: WHO". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2012-11-24. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ^ Nouveau coronavirus—Point de situation : Un nouveau cas d'infection confirmé Archived 8 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine (Novel coronavirus—Status report: A new case of confirmed infection) 12 May 2013, social-sante.gouv.fr

- ^ "MERS Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019-08-02. Archived from the original on 2019-12-07. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus infection". World Health Association. 2013-05-22. Archived from the original on 2013-06-07. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ "MERS in the U.S." Center for Disease Control. 2019-08-02. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ Sang-Hun C (2015-06-08). "MERS Virus's Path: One Man, Many South Korean Hospitals". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-07-15. Retrieved 2017-03-01.

- ^ "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)". WHO. Archived from the original on 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2019-12-10.

- ^ The Editorial Board (2020-01-29). "Is the World Ready for the Coronavirus?—Distrust in science and institutions could be a major problem if the outbreak worsens". The New York Times. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- ^ "WHO Statement Regarding Cluster of Pneumonia Cases in Wuhan, China". www.who.int. 2020-01-09. Archived from the original on 2020-01-14. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- ^ "Laboratory testing of human suspected cases of novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection. Interim guidance, 10 January 2020" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-20. Retrieved 2020-01-14.

- ^ "Novel Coronavirus 2019, Wuhan, China". www.cdc.gov (CDC). 2020-01-23. Archived from the original on 2020-01-20. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ "2019 Novel Coronavirus infection (Wuhan, China): Outbreak update". Canada.ca. 2020-01-21.

- ^ Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, et al. (February 2020). "The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 91: 264–66. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. PMC 7128332. PMID 31953166.

- ^ Cohen J (2020-01-26). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". ScienceMag American Association for the Advancement of Science. (AAAS). Archived from the original on 2020-01-27. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- ^ Eschner K (2020-01-28). "We're still not sure where the COVID-19 really came from". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 2020-01-30. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Chapter 24 - Coronaviridae". Fenner's Veterinary Virology (Fifth ed.). Academic Press. 2017. pp. 435–461. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800946-8.00024-6. ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8. S2CID 219575461.

- ^ Murphy FA, Gibbs EP, Horzinek MC, Studdart MJ (1999). Veterinary Virology. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 495–508. ISBN 978-0-12-511340-3.

- ^ a b Tirotta E, Carbajal KS, Schaumburg CS, Whitman L, Lane TE (July 2010). "Cell replacement therapies to promote remyelination in a viral model of demyelination". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 224 (1–2): 101–07. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.05.013. PMC 2919340. PMID 20627412.

- ^ a b "Merck Veterinary Manual". Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ a b Bande F, Arshad SS, Bejo MH, Moeini H, Omar AR (2015). "Progress and challenges toward the development of vaccines against avian infectious bronchitis". Journal of Immunology Research. 2015: 424860. doi:10.1155/2015/424860. PMC 4411447. PMID 25954763.

- ^ Cavanagh, D (2007). "Coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus". Veterinary Research. 38 (2): 281–97. doi:10.1051/vetres:2006055. PMID 17296157.

- ^ "Taxonomy browser (Avian coronavirus)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- ^ Zhou P, Fan H, Lan T, Yang XL, Shi WF, Zhang W, et al. (April 2018). "Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin". Nature. 556 (7700): 255–58. Bibcode:2018Natur.556..255Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0010-9. PMC 7094983. PMID 29618817.

- ^ Wei X, She G, Wu T, Xue C, Cao Y (February 2020). "PEDV enters cells through clathrin-, caveolae-, and lipid raft-mediated endocytosis and traffics via the endo-/lysosome pathway". Veterinary Research. 51 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/s13567-020-0739-7. PMC 7011528. PMID 32041637.

- ^ a b c "Taxonomy browser (Alphacoronavirus 1)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ Cruz JL, Sola I, Becares M, Alberca B, Plana J, Enjuanes L, Zuñiga S (June 2011). "Coronavirus gene 7 counteracts host defenses and modulates virus virulence". PLOS Pathogens. 7 (6): e1002090. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002090. PMC 3111541. PMID 21695242.

- ^ Cruz JL, Becares M, Sola I, Oliveros JC, Enjuanes L, Zúñiga S (September 2013). "Alphacoronavirus protein 7 modulates host innate immune response". Journal of Virology. 87 (17): 9754–67. doi:10.1128/JVI.01032-13. PMC 3754097. PMID 23824792.

- ^ a b "Taxonomy browser (Betacoronavirus 1)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ "Taxonomy browser (Alphacoronavirus)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ Murray J (2014-04-16). "What's New With Ferret FIP-like Disease?" (xls). Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- ^ "Infectious Diseases of Ferrets - Exotic and Laboratory Animals". Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ a b "Taxonomy browser (Embecovirus)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ Weiss SR, Navas-Martin S (December 2005). "Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 69 (4): 635–64. doi:10.1128/MMBR.69.4.635-664.2005. PMC 1306801. PMID 16339739.

- ^ "Enteric Coronavirus". Diseases of Research Animals. Archived from the original on 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ "COVID-19 vaccine and treatments tracker (Choose vaccines or treatments tab, apply filters to view select data)". Milken Institute. 2020-11-03. Retrieved 2020-11-03. Lay summary.

- ^ a b "COVID-19 vaccine and therapeutics tracker". BioRender. 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2020-11-03.

- ^ Dong L, Hu S, Gao J (2020). "Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics. 14 (1): 58–60. doi:10.5582/ddt.2020.01012. PMID 32147628.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coronavirus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Orthocoronavirinae. |

| Look up coronavirus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Acheson, N. H. (2011). "Chapter 14: Coronaviruses". Fundamentals of molecular virology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 159–171. ISBN 9780470900598.

- Alwan A, Mahjour J, Memish ZA (2013). "Novel coronavirus infection: time to stay ahead of the curve". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 19 Suppl 1: S3–4. doi:10.26719/2013.19.supp1.S3. PMID 23888787.

- Laude H, Rasschaert D, Delmas B, Godet M, Gelfi J, Charley B (June 1990). "Molecular biology of transmissible gastroenteritis virus". Veterinary Microbiology. 23 (1–4): 147–54. doi:10.1016/0378-1135(90)90144-K. PMC 7117338. PMID 2169670.

- Sola I, Alonso S, Zúñiga S, Balasch M, Plana-Durán J, Enjuanes L (April 2003). "Engineering the transmissible gastroenteritis virus genome as an expression vector inducing lactogenic immunity". Journal of Virology. 77 (7): 4357–69. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.7.4357-4369.2003. PMC 150661. PMID 12634392.

- Tajima M (1970). "Morphology of transmissible gastroenteritis virus of pigs. A possible member of coronaviruses. Brief report". Archiv für die Gesamte Virusforschung. 29 (1): 105–08. doi:10.1007/BF01253886. PMC 7086923. PMID 4195092. S2CID 42104521.

| Classification |

|---|

Information

Article Coronavirus in English Wikipedia took following places in local popularity ranking:

- 10 place in 2020-04-02

- 11 place in 2020-04-03

- 10 place in 2020-04-04

- 6 place in 2020-04-05

- 15 place in 2020-04-06

- 30 place in 2020-04-07

- 30 place in 2020-04-08

- 29 place in 2020-04-09

- 17 place in 2020-04-10

- 7 place in 2020-04-11

- 10 place in 2020-04-12

- 5 place in 2020-04-13

- 8 place in 2020-04-14

- 6 place in 2020-04-15

- 7 place in 2020-04-16

- 8 place in 2020-04-17

- 7 place in 2020-04-18

- 7 place in 2020-04-19

- 9 place in 2020-04-20

- 9 place in 2020-04-21

- 7 place in 2020-04-22

- 21 place in 2020-04-23

- 26 place in 2020-04-24

- 53 place in 2020-04-25

- 59 place in 2020-04-26

- 26 place in 2020-04-27

- 39 place in 2020-04-28

- 47 place in 2020-04-29

- 42 place in 2020-04-30

- 51 place in 2020-05-01

- 48 place in 2020-05-02

- 49 place in 2020-05-03

- 49 place in 2020-05-04

- 44 place in 2020-05-05

- 47 place in 2020-05-06

- 50 place in 2020-05-07

- 60 place in 2020-05-08

- 74 place in 2020-05-09

- 87 place in 2020-05-10

- 66 place in 2020-05-11

- 58 place in 2020-05-12

- 46 place in 2020-05-13

- 47 place in 2020-05-14

- 48 place in 2020-05-15

- 52 place in 2020-05-16

- 80 place in 2020-05-17

- 84 place in 2020-05-18

- 80 place in 2020-05-19

- 82 place in 2020-05-20

- 85 place in 2020-05-21

- 93 place in 2020-05-22

- 99 place in 2020-05-25

- 84 place in 2020-05-26

- 85 place in 2020-05-27

- 84 place in 2020-05-28

About the page

Presented content of the Wikipedia article was extracted in 2021-06-13 based on https://en.wikipedia.org/?curid=201983