Christopher Columbus

Admiral of the Ocean Sea Christopher Columbus | |

|---|---|

Posthumous portrait of Columbus by Sebastiano del Piombo, 1519. There are no known authentic portraits of Columbus.[1] | |

| 1st Governor of the Indies | |

| In office 1492–1499 | |

| Appointed by | Isabella I of Castile |

| Succeeded by | Francisco de Bobadilla |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Between 25 August and 31 October 1451 Genoa, Republic of Genoa |

| Died | 20 May 1506 (aged 54) Valladolid, Castile |

| Resting place | Seville Cathedral, Seville, Spain |

| Spouse(s) | Filipa Moniz Perestrelo |

| Domestic partner | Beatriz Enríquez de Arana |

| Children | Diego Fernando |

| Parents | Domenico Colombo Susanna Fontanarossa |

| Relatives | Brothers: Giovanni Pellegrino Giacomo (also called Diego)[2] Bartholomew Sister: Bianchinetta Columbus |

| Occupation | Maritime explorer |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Rank | Admiral of the Ocean Sea |

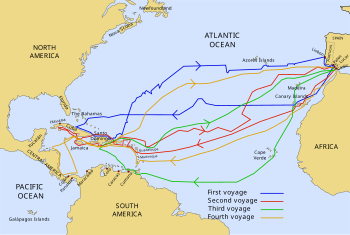

Christopher Columbus[a] (/kəˈlʌmbəs/;[3] born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was an Italian[b] explorer and navigator who completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean, opening the way for the widespread European exploration and colonization of the Americas. His expeditions, sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, were the first European contact with the Caribbean, Central America, and South America.

The name Christopher Columbus is the Anglicisation of the Latin Christophorus Columbus. Scholars generally agree that Columbus was born in the Republic of Genoa and spoke a dialect of Ligurian as his first language. He went to sea at a young age and travelled widely, as far north as the British Isles and as far south as what is now Ghana. He married Portuguese noblewoman Filipa Moniz Perestrelo and was based in Lisbon for several years, but later took a Castilian mistress; he had one son with each woman. Though largely self-educated, Columbus was widely read in geography, astronomy, and history. He formulated a plan to seek a western sea passage to the East Indies, hoping to profit from the lucrative spice trade. Following Columbus's persistent lobbying to multiple kingdoms, Catholic Monarchs Queen Isabella I and King Ferdinand II agreed to sponsor a journey west. Columbus left Castile in August 1492 with three ships and made landfall in the Americas on 12 October (ending the period of human habitation in the Americas now referred to as the pre-Columbian era). His landing place was an island in the Bahamas, known by its native inhabitants as Guanahani. Columbus subsequently visited the islands now known as Cuba and Hispaniola, establishing a colony in what is now Haiti. Columbus returned to Castile in early 1493, bringing a number of captured natives with him. Word of his voyages soon spread throughout Europe.

Columbus made three further voyages to the Americas, exploring the Lesser Antilles in 1493, Trinidad and the northern coast of South America in 1498, and the eastern coast of Central America in 1502. Many of the names he gave to geographical features—particularly islands—are still in use. He also gave the name indios ("Indians") to the indigenous peoples he encountered. The extent to which he was aware that the Americas were a wholly separate landmass is uncertain; he never clearly renounced his belief that he had reached the Far East. As a colonial governor, Columbus was accused by his contemporaries of significant brutality and was soon removed from the post. Columbus's strained relationship with the Crown of Castile and its appointed colonial administrators in America led to his arrest and removal from Hispaniola in 1500, and later to protracted litigation over the benefits that he and his heirs claimed were owed to them by the crown. Columbus's expeditions inaugurated a period of exploration, conquest, and colonization that lasted for centuries, helping create the modern Western world. The transfers between the Old World and New World that followed his first voyage are known as the Columbian exchange.

Columbus was widely venerated in the centuries after his death, but public perception has fractured in recent decades as scholars have given greater attention to the harms committed under his governance, particularly the beginning of the depopulation of Hispaniola's indigenous Taínos from mistreatment and European diseases, as well as their enslavement. Proponents of the Black Legend theory of history claim that Columbus has been unfairly maligned as part of a wider anti-Catholic sentiment. Many places in the Western Hemisphere bear his name, including the country of Colombia, the District of Columbia, and British Columbia.

Early life

Columbus's early life is obscure, but scholars believe he was born in the Republic of Genoa between 25 August and 31 October 1451.[5] His father was Domenico Colombo,[8] a wool weaver who worked both in Genoa and Savona and who also owned a cheese stand at which young Christopher worked as a helper. His mother was Susanna Fontanarossa.[8][c] He had three brothers—Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pellegrino, and Giacomo (also called Diego),[2] as well as a sister named Bianchinetta.[9] His brother Bartolomeo worked in a cartography workshop in Lisbon for at least part of his adulthood.[10]

His native language is presumed to have been a Genoese dialect although Columbus never wrote in that language. His name in the 16th-century Genoese language would have been Cristoffa[11] Corombo[12] (Ligurian pronunciation: [kriˈʃtɔffa kuˈɹuŋbu]).[13][14] His name in Italian is Cristoforo Colombo, and in Spanish Cristóbal Colón.[8]

In one of his writings, he says he went to sea at the age of 10. In 1470, the Columbus family moved to Savona, where Domenico took over a tavern. In the same year, Christopher was on a Genoese ship hired in the service of René of Anjou to support his attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples. Some modern authors have argued that he was not from Genoa but, instead, from the Aragon region of Spain[15] or from Portugal.[16] These competing hypotheses have generally been discounted by mainstream scholars.[17][18]

In 1473, Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the wealthy Spinola, Centurione, and Di Negro families of Genoa. Later, he made a trip to Chios, an Aegean island then ruled by Genoa.[19] In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry valuable cargo to northern Europe. He probably docked in Bristol, England,[20] and Galway, Ireland. He may have also gone to Iceland in 1477.[8][21][22] It is known that in the autumn of 1477, he sailed on a Portuguese ship from Galway to Lisbon, where he found his brother Bartolomeo, and they continued trading for the Centurione family. Columbus based himself in Lisbon from 1477 to 1485. He married Filipa Moniz Perestrelo, daughter of the Porto Santo governor and Portuguese nobleman of Lombard origin Bartolomeu Perestrello.[23]

In 1479 or 1480, Columbus's son Diego was born. Between 1482 and 1485, Columbus traded along the coasts of West Africa, reaching the Portuguese trading post of Elmina at the Guinea coast (in present-day Ghana).[24] Before 1484, Columbus returned to Porto Santo to find that his wife had died.[25] He returned to Portugal to settle her estate and take his son Diego with him.[26] He left Portugal for Castile in 1485, where he found a mistress in 1487, a 20-year-old orphan named Beatriz Enríquez de Arana.[27] It is likely that Beatriz met Columbus when he was in Córdoba, a gathering site of many Genoese merchants and where the court of the Catholic Monarchs was located at intervals. Beatriz, unmarried at the time, gave birth to Columbus's natural son, Fernando Columbus in July 1488, named for the monarch of Aragon. Columbus recognized the boy as his offspring. Columbus entrusted his older, legitimate son Diego to take care of Beatriz and pay the pension set aside for her following his death, but Diego was negligent in his duties.[28]

Ambitious, Columbus eventually learned Latin, Portuguese, and Castilian. He read widely about astronomy, geography, and history, including the works of Claudius Ptolemy, Pierre Cardinal d'Ailly's Imago Mundi, the travels of Marco Polo and Sir John Mandeville, Pliny's Natural History, and Pope Pius II's Historia Rerum Ubique Gestarum. According to historian Edmund Morgan,

Columbus was not a scholarly man. Yet he studied these books, made hundreds of marginal notations in them and came out with ideas about the world that were characteristically simple and strong and sometimes wrong ...[29]

Quest for Asia

Background

Under the Mongol Empire's hegemony over Asia and the Pax Mongolica, Europeans had long enjoyed a safe land passage, the Silk Road, to Maritime Southeast Asia, parts of East Asia, and China, which were sources of valuable goods. With the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, the Silk Road was closed to Christian traders.[30]

In 1470, the Florentine astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli suggested to King Afonso V of Portugal that sailing west across the Atlantic would be a quicker way to reach the Maluku (Spice) Islands, China, and Japan than the route around Africa, but Afonso rejected his proposal.[31] In the 1480s, the Columbus brothers proposed a plan to reach the East Indies by sailing west. By 1481, Toscanelli had sent Columbus a map implying that a westward route to Asia was possible.[32][33] Columbus's plans were complicated by the opening of the Cape Route to Asia around Africa in 1488.[34]

Carol Delaney and others have argued that Columbus was a Christian millennialist and apocalypticist and that these beliefs motivated his quest for Asia in a variety of ways.[35] Columbus often wrote about seeking gold in the diaries of his voyages and writes about acquiring the precious metal "in such quantity that the sovereigns... will undertake and prepare to go conquer the Holy Sepulcher" in a fulfillment of Biblical prophecy.[35][d] Columbus also often wrote about converting all races to Christianity.[35] Abbas Hamandi argues that Columbus was motivated by the hope of "[delivering] Jerusalem from Muslim hands" by "using the resources of newly discovered lands".[37]

Geographical considerations

Despite a popular misconception to the contrary, nearly all educated Westerners understood that the Earth is spherical, a successful theory rooted in antiquity.[38] By Columbus's time, the techniques of celestial navigation, which use the position of the Sun and the stars in the sky, had long been in use by astronomers and were beginning to be implemented by mariners.[39]

As far back as the 3rd century BC, Eratosthenes had correctly computed the circumference of the Earth by using simple geometry and studying the shadows cast by objects at two remote locations.[40][41] In the 1st century BC, Posidonius confirmed Eratosthenes's results by comparing stellar observations at two separate locations. These measurements were widely known among scholars, but Ptolemy's use of the smaller, old-fashioned units of distance led Columbus to underestimate the size of the Earth by about a third.[42]

From Pierre d'Ailly's Imago Mundi (1410), Columbus learned of Alfraganus's estimate that a degree of latitude (or a degree of longitude along the equator) spanned 562⁄3 Arabic miles (equivalent to 66.2 nautical miles or 122.6 kilometres), but he did not realize that this was expressed in the Arabic mile (about 1,830 meters) rather than the shorter Roman mile (about 1,480 meters) with which he was familiar.[44] Columbus therefore estimated the size of the Earth to be about 75% of Eratosthenes's calculation, and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan as 2,400 nautical miles (about 23% of the real figure).[45]

Furthermore, most scholars accepted Ptolemy's estimate that Eurasia spanned 180° longitude, rather than the actual 130° (to the Chinese mainland) or 150° (to Japan at the latitude of Spain). Columbus, for his part, believed an even higher estimate, leaving a smaller percentage for water. In d'Ailly's Imago Mundi, Columbus read Marinus of Tyre's estimate that the longitudinal span of Eurasia was 225°.[46] Some have suggested he followed the statement in 2 Esdras (6:42) that "six parts [of the globe] are habitable and the seventh is covered with water."[47] He was also aware of Marco Polo's claim that Japan (which he called "Cipangu") was some 2,414 kilometres (1,500 mi) to the east of China ("Cathay"),[46] and closer to the equator than it is. He was influenced by Toscanelli's idea that there were inhabited islands even farther to the east than Japan, including the mythical Antillia, which he thought might lie not much farther to the west than the Azores.[47]

Columbus therefore would have estimated the distance from the Canary Islands west to Japan to be about 9,800 kilometres (5,300 nmi) or 3,700 kilometres (2,000 nmi), depending on which estimate he used for Eurasia's longitudinal span. The true figure is now known to be vastly larger: about 20,000 kilometres (11,000 nmi).[48] No ship in the 15th century could have carried enough food and fresh water for such a long voyage, and the dangers involved in navigating through the uncharted ocean would have been formidable. Most European navigators reasonably concluded that a westward voyage from Europe to Asia was unfeasible. The Catholic Monarchs, however, having completed the Reconquista, an expensive war in the Iberian Peninsula, were eager to obtain a competitive edge over other European countries in the quest for trade with the Indies. Columbus's project, though far-fetched, held the promise of such an advantage.[49]

Nautical considerations

Though Columbus was wrong about the number of degrees of longitude that separated Europe from the Far East and about the distance that each degree represented, he did utilize the trade winds, which would prove to be the key to his successful navigation of the Atlantic Ocean.[50] He planned to first sail to the Canary Islands before continuing west by utilizing the northeast trade wind.[51] Part of the return to Spain would require traveling against the wind using an arduous sailing technique called beating, during which almost no progress can be made.[52] To effectively make the return voyage, Columbus would need to follow the curving trade winds northeastward to the middle latitudes of the North Atlantic, where he would be able to catch the "westerlies" that blow eastward to the coast of Western Europe.[53]

The navigational technique for travel in the Atlantic appears to have been exploited first by the Portuguese, who referred to it as the volta do mar ('turn of the sea'). Columbus's knowledge of the Atlantic wind patterns was imperfect at the time of his first voyage. By sailing due west from the Canary Islands during hurricane season, skirting the so-called horse latitudes of the mid-Atlantic, Columbus risked both being becalmed and running into a tropical cyclone, both of which he avoided by chance.[54]

Quest for financial support for a voyage

By about 1484, Columbus proposed his planned voyage to King John II of Portugal.[55] The king submitted Columbus's proposal to his experts, who rejected it on the correct belief that Columbus's estimate for a voyage of 2,400 nautical miles was only a quarter of what it should have been.[56] In 1488, Columbus again appealed to the court of Portugal, resulting in John II again inviting him for an audience. That meeting also proved unsuccessful, in part because not long afterwards Bartolomeu Dias returned to Portugal with news of his successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa (near the Cape of Good Hope).[57]

Columbus sought an audience from the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, who had united several kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula by marrying and were ruling together. On 1 May 1486, permission having been granted, Columbus presented his plans to Queen Isabella, who, in turn, referred it to a committee. The savants of Spain, like their counterparts in Portugal, replied that Columbus had grossly underestimated the distance to Asia. They pronounced the idea impractical and advised the Catholic Monarchs to pass on the proposed venture. To keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the sovereigns gave him an allowance, totaling about 14,000 maravedis for the year, or about the annual salary of a sailor.[58] In May 1489, the queen sent him another 10,000 maravedis, and the same year the monarchs furnished him with a letter ordering all cities and towns under their domain to provide him food and lodging at no cost.[59]

Columbus also dispatched his brother Bartholomew to the court of Henry VII of England to inquire whether the English crown might sponsor his expedition, but he was captured by pirates in the process, and only arrived in early 1491.[60] By that time, Columbus had retreated to La Rábida Friary, where the Spanish crown sent him 20,000 maravedis to buy new clothes and instructions to return to the Spanish court for renewed discussions.[61]

Agreement with the Spanish crown

Columbus waited at King Ferdinand's camp until Ferdinand and Isabella conquered Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula, in January 1492. A council led by Isabella's confessor, Hernando de Talavera, found Columbus's proposal to reach the Indies implausible. Columbus had left for France when Ferdinand intervened,[e] first sending Talavera and Bishop Diego Deza to appeal to the queen.[63] Isabella was finally convinced by the king's clerk Luis de Santángel, who argued that Columbus would bring his ideas elsewhere, and offered to help arrange the funding. Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch Columbus, who had travelled several kilometers toward Córdoba.[63]

In the April 1492 "Capitulations of Santa Fe", King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella promised Columbus that if he succeeded he would be given the rank of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and appointed Viceroy and Governor of all the new lands he could claim for Spain. He had the right to nominate three persons, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands. He would be entitled to 10 percent of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity. Additionally, he would also have the option of buying one-eighth interest in any commercial venture with the new lands and receive one-eighth of the profits.[47]

In 1500, during his third voyage to the Americas, Columbus was arrested and dismissed from his posts. He and his sons, Diego and Fernando, then conducted a lengthy series of court cases against the Castilian crown, known as the pleitos colombinos, alleging that the Crown had illegally reneged on its contractual obligations to Columbus and his heirs. The Columbus family had some success in their first litigation, as a judgment of 1511 confirmed Diego's position as viceroy but reduced his powers. Diego resumed litigation in 1512, which lasted until 1536, and further disputes continued until 1790.[64]

Voyages

Between 1492 and 1504, Columbus completed four round-trip voyages between Spain and the Americas, each voyage being sponsored by the Crown of Castile. On his first voyage, he independently discovered the Americas. These voyages marked the beginning of the European exploration and colonization of the Americas, and are thus important to both the Age of Discovery and Western history writ large.[10]

Columbus always insisted, in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary, that the lands that he visited during those voyages were part of the Asian continent, as previously described by Marco Polo and other European travelers.[10] Columbus's refusal to acknowledge that the lands he had visited and claimed for Spain were not part of Asia might explain, in part, why the American continent was named after the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci—who received credit for recognizing it as a "New World"—and not after Columbus.[65][f]

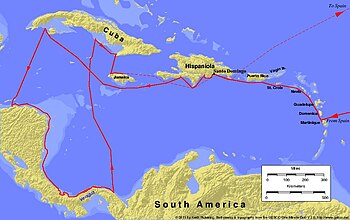

First voyage (1492–1493)

On the evening of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera with three ships. The largest was a carrack, the Santa María, owned and captained by Juan de la Cosa, and under Columbus's direct command.[69] The other two were smaller caravels, the Pinta and the Niña,[70] piloted by the Pinzón brothers.[69] Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands. There he restocked provisions and made repairs then departed from San Sebastián de La Gomera on 6 September,[71] for what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean.

On 7 October, the crew spotted "[i]mmense flocks of birds".[72] On 11 October, Columbus changed the fleet's course to due west, and sailed through the night, believing land was soon to be found. At around 02:00 the following morning, a lookout on the Pinta, Rodrigo de Triana, spotted land. The captain of the Pinta, Martín Alonso Pinzón, verified the sight of land and alerted Columbus.[73][74] Columbus later maintained that he had already seen a light on the land a few hours earlier, thereby claiming for himself the lifetime pension promised by Ferdinand and Isabella to the first person to sight land.[34][75] Columbus called this island (in what is now the Bahamas) San Salvador (meaning "Holy Savior"); the natives called it Guanahani.[76][h] Christopher Columbus's journal entry of 12 October 1492 states:

Many of the men I have seen have scars on their bodies, and when I made signs to them to find out how this happened, they indicated that people from other nearby islands come to San Salvador to capture them; they defend themselves the best they can. I believe that people from the mainland come here to take them as slaves. They ought to make good and skilled servants, for they repeat very quickly whatever we say to them. I think they can very easily be made Christians, for they seem to have no religion. If it pleases our Lord, I will take six of them to Your Highnesses when I depart, in order that they may learn our language.[78]

Columbus called the inhabitants of the lands that he visited Los Indios (Spanish for "Indians").[79] He initially encountered the Lucayan, Taíno, and Arawak peoples. Noting their gold ear ornaments, Columbus took some of the Arawaks prisoner and insisted that they guide him to the source of the gold.[80] Columbus noted that their primitive weapons and military tactics made the natives susceptible to easy conquest, writing, "these people are very simple in war-like matters ... I could conquer the whole of them with 50 men, and govern them as I pleased."[81]

Columbus also explored the northeast coast of Cuba, where he landed on 28 October. On 22 November, Martín Alonso Pinzón took the Pinta on an unauthorized expedition in search of an island called "Babeque" or "Baneque", which the natives had told him was rich in gold. Columbus, for his part, continued to the northern coast of Hispaniola, where he landed on 5 December.[82] There, the Santa María ran aground on Christmas Day 1492 and had to be abandoned. The wreck was used as a target for cannon fire to impress the native peoples.[34] Columbus was received by the native cacique Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus left 39 men, including the interpreter Luis de Torres,[83][i] and founded the settlement of La Navidad, in present-day Haiti.[84] Columbus took more natives prisoner and continued his exploration.[80] He kept sailing along the northern coast of Hispaniola with a single ship, until he encountered Pinzón and the Pinta on 6 January.

On 13 January 1493, Columbus made his last stop of this voyage in the Americas, in the Bay of Rincón in northeast Hispaniola.[85] There he encountered the Ciguayos, the only natives who offered violent resistance during this voyage.[86] The Ciguayos refused to trade the amount of bows and arrows that Columbus desired; in the ensuing clash one Ciguayo was stabbed in the buttocks and another wounded with an arrow in his chest.[87] Because of these events, Columbus called the inlet the Bay of Arrows.[88]

Columbus headed for Spain on the Niña, but a storm separated him from the Pinta, and forced the Niña to stop at the island of Santa Maria in the Azores. Half of his crew went ashore to say prayers in a chapel to give thanks for having survived the storm. But while praying, they were imprisoned by the governor of the island, ostensibly on suspicion of being pirates. After a two-day standoff, the prisoners were released, and Columbus again set sail for Spain.[89]

Another storm forced Columbus into the port at Lisbon.[34] From there he went to Vale do Paraíso north of Lisbon to meet King John II of Portugal, who told Columbus that he believed the voyage to be in violation of the 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas. After spending more than a week in Portugal, Columbus set sail for Spain. Returning on 15 March 1493, he was given a warm welcome by the monarchs.

Columbus's letter on the first voyage, was instrumental in spreading the news throughout Europe about his voyage. Almost immediately after his arrival in Spain, printed versions began to appear. Word of his voyage rapidly spread throughout Europe. Most people initially believed that he had reached Asia.[90] The Bulls of Donation, three papal bulls of Pope Alexander VI delivered in 1493 purported to grant overseas territories to Portugal and the Catholic Monarchs of Spain. They were replaced by the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494.[91]

Second voyage (1493–1496)

On 24 September 1493, Columbus sailed from Cádiz with 17 ships, and supplies to establish permanent colonies in the Americas. He sailed with 1,200 men, including priests, farmers, and soldiers. The fleet stopped at the Canary Islands, continuing three weeks later on a more southerly course than on the first voyage.

On 3 November, they arrived in the Windward Islands and landed at Marie-Galante, now part of Guadeloupe. These islands were named by Columbus on this voyage, as well as Montserrat, Antigua, Saint Martin, the Virgin Islands, and many others.

On 22 November, Columbus returned to Hispaniola to visit La Navidad, where 39 Spaniards had been left during the first voyage. Columbus found the fort in ruins, destroyed by the Taínos after some of the Spaniards had formed a murderous gang in pursuit of gold and women.[93][94] Columbus then established a poorly located and short-lived settlement, La Isabela, in the present-day Dominican Republic.[95]

From April to August 1494, Columbus explored Cuba and Jamaica, then returned to Hispaniola. By the end of 1494, disease and famine had killed two-thirds of the Spanish settlers.[96][97] Columbus implemented encomienda,[98][99] a Spanish labor system that rewarded conquerors with the labor of conquered non-Christian people. Columbus executed Spanish colonists for minor crimes, and used dismemberment as punishment.[100] Columbus and the colonists enslaved the indigenous people,[101] including children.[102] Natives were beaten, raped, and tortured for the location of imagined gold.[103] Thousands committed suicide rather than face the oppression.[104][k]

In February 1495, Columbus took over 1,500 Arawaks, some of whom had rebelled.[80][106] About 500 of them were shipped to Spain as slaves, with about 40% dying en route.[80][106][107]

In June 1495, the Spanish crown sent ships and supplies to Hispaniola. In October, Florentine merchant Gianotto Berardi received almost 40,000 maravedís worth of slaves.[108]

On 10 March 1496, having been away about 30 months,[109] the fleet departed La Isabela, landing in Portugal on 8 June.

Third voyage (1498–1500)

On 30 May 1498, Columbus left with six ships from Sanlúcar, Spain. Three of the ships headed directly for Hispaniola with much-needed supplies. Columbus took the other three to continue the search for a passage to continental Asia.[110]

On 31 July they sighted Trinidad.[111] On 1 August, they arrived near the mouth of South America's Orinoco river. Columbus recognized that it must be the continent's mainland.[112] On 5 August, they landed on the mainland of South America at the Paria Peninsula.[113] They then sailed to the islands of Chacachacare and Margarita (reaching the latter on 14 August),[114] and sighted Tobago and Grenada.[115]

On 19 August, Columbus returned to Hispaniola. There he found settlers in rebellion against his rule, and his promises of riches. Columbus had some of his crew hanged for disobedience.

In October 1499, Columbus sent two ships to Spain, asking the Court of Spain to appoint a royal commissioner to help him govern.[116] By this time, accusations of tyranny and incompetence on the part of Columbus had also reached the Court. The sovereigns replaced Columbus with Francisco de Bobadilla, a member of the Order of Calatrava, who was tasked with investigating the accusations of brutality made against Columbus. Arriving in Santo Domingo while Columbus was away, Bobadilla was immediately met with complaints about all three Columbus brothers.[117] Bobadilla reported to Spain that Columbus regularly used torture and mutilation to govern Hispaniola.[l]

According to the report, Columbus once punished a man found guilty of stealing corn by having his ears and nose cut off and then selling him into slavery. Testimony recorded in the report stated that Columbus congratulated his brother Bartolomeo on "defending the family" when the latter ordered a woman paraded naked through the streets and then had her tongue cut out for suggesting that Columbus was of lowly birth.[118] The document also describes how Columbus put down native unrest and revolt: he first ordered a brutal crackdown in which many natives were killed, and then paraded their dismembered bodies through the streets in an attempt to discourage further rebellion.[119]

In early October 1500, Columbus and Diego presented themselves to Bobadilla, and were put in chains aboard La Gorda, Columbus's own ship.[120] They were returned to Spain, and lingered in jail for six weeks before King Ferdinand ordered their release. Not long after, the king and queen summoned the Columbus brothers to the Alhambra palace in Granada. There, the royal couple heard the brothers' pleas; restored their freedom and wealth; and, after much persuasion, agreed to fund Columbus's fourth voyage. However, Nicolás de Ovando was to be the new governor of the West Indies.[121]

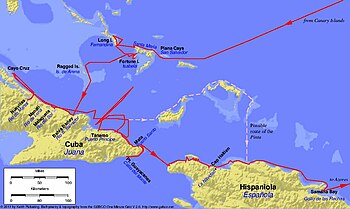

Fourth voyage (1502–1504)

On 11 May 1502 Columbus, with his brother and son, left Cadiz with his flagship Santa María and three other vessels. He sailed to Arzila on the Moroccan coast to rescue Portuguese soldiers said to be besieged by the Moors.

On 15 June, they arrived at Martinique. A hurricane was brewing, so he continued on, hoping to find shelter on Hispaniola. He arrived at Santo Domingo on 29 June, but was denied port, and the new governor refused to listen to his storm prediction. Instead, while Columbus's ships sheltered at the mouth of the Rio Jaina, the first Spanish treasure fleet sailed into the hurricane. Columbus's ships survived with only minor damage, while 29 of the 30 ships in the governor's fleet were lost along with 500 lives (including that of Francisco de Bobadilla) and over US$10 million of Columbus's gold. A fragile ship carrying Columbus's personal belongings was the sole vessel to reach Spain.[122][123]

After a brief stop at Jamaica, Columbus sailed to Central America, arriving at the coast of Honduras on 30 July. Here Bartolomeo found native merchants and a large canoe. On 14 August, he landed on the continental mainland at Puerto Castilla, Honduras. He spent two months exploring the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, before arriving in Almirante, Bocas del Toro in Panama on 16 October.

In Panama, Columbus learned from the Ngobe of gold and a strait to another ocean. In January 1503, he established a garrison at the mouth of the Belén River. Columbus left for Hispaniola on 16 April. On 10 May he sighted the Cayman Islands, naming them "Las Tortugas" after the numerous sea turtles there.[124] His ships sustained damage in a storm off the coast of Cuba.[124] Unable to travel farther, on 25 June 1503 they were beached in Saint Ann Parish, Jamaica.[125]

For one year Columbus and his men remained stranded on Jamaica. A Spaniard, Diego Méndez, and some natives paddled a canoe to get help from Hispaniola. The governor, Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres, detested Columbus and obstructed all efforts to rescue him and his men. In the meantime Columbus, in a desperate effort to induce the natives to continue provisioning him and his hungry men, won their favor by predicting a lunar eclipse for 29 February 1504, using Abraham Zacuto's astronomical charts.[126][127][128] Help finally arrived, no thanks to the governor, on 29 June 1504, and Columbus and his men arrived in Sanlúcar, Spain, on 7 November.

Later life, illness, and death

Columbus had always claimed the conversion of non-believers as one reason for his explorations, but he grew increasingly religious in his later years. Probably with the assistance of his son Diego and his friend the Carthusian monk Gaspar Gorricio, Columbus produced two books during his later years: a Book of Privileges (1502), detailing and documenting the rewards from the Spanish Crown to which he believed he and his heirs were entitled, and a Book of Prophecies (1505), in which passages from the Bible were used to place his achievements as an explorer in the context of Christian eschatology.[10]

In his later years, Columbus demanded that the Spanish Crown give him 10 percent of all profits made in the new lands, as stipulated in the Capitulations of Santa Fe. Because he had been relieved of his duties as governor, the crown did not feel bound by that contract and his demands were rejected. After his death, his heirs sued the Crown for a part of the profits from trade with America, as well as other rewards. This led to a protracted series of legal disputes known as the pleitos colombinos ("Columbian lawsuits").[129]

During a violent storm on his first return voyage, Columbus, then 41, suffered an attack of what was believed at the time to be gout. In subsequent years, he was plagued with what was thought to be influenza and other fevers, bleeding from the eyes, temporary blindness and prolonged attacks of gout. The attacks increased in duration and severity, sometimes leaving Columbus bedridden for months at a time, and culminated in his death 14 years later.

Based on Columbus's lifestyle and the described symptoms, modern doctors suspect that he suffered from reactive arthritis, rather than gout.[131][132] Reactive arthritis is a joint inflammation caused by intestinal bacterial infections or after acquiring certain sexually transmitted diseases (primarily chlamydia or gonorrhea). "It seems likely that [Columbus] acquired reactive arthritis from food poisoning on one of his ocean voyages because of poor sanitation and improper food preparation," writes Dr. Frank C. Arnett, a rheumatologist and professor of internal medicine, pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston.[131]

On 20 May 1506, aged 54, Columbus died in Valladolid, Spain.[133]

Location of remains

Columbus's remains were first buried at a convent in Valladolid,[134] then moved to the monastery of La Cartuja in Seville (southern Spain) by the will of his son Diego.[135] They may have been exhumed in 1513 and interred at the Cathedral of Seville.[134] In about 1536, the remains of both Columbus and his son Diego were moved to a cathedral in Colonial Santo Domingo, in the present-day Dominican Republic.[134] By some accounts, around 1796, when France took over the entire island of Hispaniola, Columbus's remains were moved to Havana, Cuba.[134] After Cuba became independent following the Spanish–American War in 1898, the remains were moved back to the Cathedral of Seville, Spain,[134] where they were placed on an elaborate catafalque. In June 2003, DNA samples were taken from these remains[136][m] as well as those of Columbus's brother Diego and younger son Fernando. Initial observations suggested that the bones did not appear to match Columbus's physique or age at death.[138] DNA extraction proved difficult; only short fragments of mitochondrial DNA could be isolated. These matched corresponding DNA from Columbus's brother, supporting that both individuals had shared the same mother.[139] Such evidence, together with anthropologic and historic analyses, led the researchers to conclude that the remains belonged to Christopher Columbus.[140][c]

In 1877, a priest discovered a lead box at Santo Domingo inscribed: "Discoverer of America, First Admiral". Inscriptions found the next year read "Last of the remains of the first admiral, Sire Christopher Columbus, discoverer."[142] The box contained bones of an arm and a leg, as well as a bullet.[n] These remains were considered legitimate by physician and U.S. Assistant Secretary of State John Eugene Osborne, who suggested in 1913 that they travel through the Panama Canal as a part of its opening ceremony.[144][o] These remains were kept at the Basilica Cathedral of Santa María la Menor before being moved to the Columbus Lighthouse (inaugurated in 1992). The authorities in Santo Domingo have never allowed these remains to be exhumed, so it is unconfirmed whether they are from Columbus's body as well.[139][140][p]

Commemoration

Veneration of Columbus in the U.S. dates back to colonial times. The use of Columbus as a founding figure of New World nations spread rapidly after the American Revolution. This was out of a desire to develop a national history and founding myth with fewer ties to Britain.[146] In the U.S., his name was given to the federal capital (District of Columbia), the capitals of two U.S. states (Ohio and South Carolina), the Columbia River, and monuments like Columbus Circle.

Columbus's name was given to the Republic of Colombia. Towns, streets, and plazas throughout Latin America and Spain have been named after him.

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of the landing of Columbus,[147] the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago was named the World's Columbian Exposition. The U.S. Postal Service issued the first U.S. commemorative stamps, the Columbian Issue depicting Columbus, Queen Isabella and others in various stages of his several voyages.

For the Columbus Quincentenary in 1992, a second Columbian issue was released jointly with Italy, Portugal, and Spain.[148] Columbus was celebrated at Seville Expo '92, and Genoa Expo '92.

In 1909, descendants of Columbus dismantled and moved the Columbus family chapel in Spain to Boalsburg near State College, Pennsylvania, where it may be visited by the public.[149]

In many countries of the Americas, as well as Spain and Italy, Columbus Day celebrates the anniversary of Columbus's arrival in the Americas on 12 October 1492.

Legacy

The voyages of Columbus are considered a turning point in world history, marking the beginning of globalization and accompanying demographic, commercial, economic, social, and political changes.[150] His explorations resulted in permanent contact between the two hemispheres, and the term "pre-Columbian" is used to refer to the culture of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus and his European successors. The ensuing Columbian exchange saw the massive exchange of animals, plants, fungi, diseases, technologies, mineral wealth and ideas.[151]

Until the 1990s, Columbus was portrayed as a heroic explorer. More recently, however, the narrative has featured the negative effects of the conquest on native populations.[152] Exposed to Old World diseases, the indigenous populations of the New World collapsed and were largely replaced by Europeans and Africans who brought with them new methods of farming, business, governance, and religious worship.[153]

Originality of discovery of America

Though Christopher Columbus came to be considered the European discoverer of America in Western popular culture, his historical legacy is more nuanced.[q] The Norse had colonized North America around 500 years before Columbus, with some degree of contact with Europe being maintained until about 1410.[154] The 1960s discovery at L'Anse aux Meadows put Columbus's role in Western popular culture into question, as it partially corroborates accounts within the Icelandic sagas of Erik the Red's colonization of Greenland and his son Leif Erikson's exploration of Vinland around the turn of the 11th century.[155][156]

America as a distinct land

Historians have traditionally argued that Columbus remained convinced until his death that his journeys had been along the east coast of Asia as he originally intended.[157][146] On his third voyage he briefly referred to South America as a "hitherto unknown" continent,[f] while also rationalizing that it was the "Earthly Paradise" located "at the end of the Orient".[112] Columbus continued to claim in his later writings that he had reached Asia; in a 1502 letter to Pope Alexander VI, he asserts that Cuba is the east coast of Asia.[158] On the other hand, in a document in the Book of Privileges (1502), Columbus refers to the New World as the Indias Occidentales ('West Indies'), which he says "were unknown to all the world".[159]

Flat Earth mythology

Washington Irving's 1828 biography of Columbus popularized the idea that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because many Catholic theologians insisted that the Earth was flat,[160] but this is a popular misconception which can be traced back to 17th-century Protestants campaigning against Catholicism.[161] In fact, the spherical shape of the Earth had been known to scholars since antiquity, and was common knowledge among sailors, including Columbus.[162][r] Coincidentally, the oldest surviving globe of the Earth, the Erdapfel, was made in 1492, just before Columbus's return to Europe. As such it contains no sign of the Americas and yet demonstrates the common belief in a spherical Earth.[164]

Criticism and defense

Columbus is criticized both for his brutality and for initiating the depopulation of the indigenous Americans, whether by disease or intentional genocide. Some defend his actions or allege the worst of them are not based in fact.

As a result of the protests and riots that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020, many public monuments of Christopher Columbus have been removed.[165]

Brutality

Some historians have criticized Columbus for initiating colonization and for abusing natives.[166][80][167][168] On St. Croix, Columbus's friend Michele da Cuneo—according to his own account—kept an indigenous woman he captured, whom Columbus "gave to [him]", then brutally raped her.[169][s][t] The punishment for an indigenous person, aged 14 and older, failing to pay a hawk's bell of gold dust (based on Bartolomé de las Casas' account, about $400 in 2021 currency)[172][173] every three months was cutting off the hands of those without tokens, often leaving them to bleed to death.[80][174] Columbus had an economic interest in the enslavement of the Hispaniola natives and for that reason was not eager to baptize them, which attracted criticism from some churchmen.[175] Consuelo Varela, a Spanish historian who has seen the report, states that "Columbus's government was characterised by a form of tyranny. Even those who loved him had to admit the atrocities that had taken place."[118]

Kris Lane disputes whether it is appropriate to use the term "genocide" when the atrocities were not Columbus's intent, but resulted from his decrees, family business goals, and negligence.[100] Other historians have argued that some of the accounts of the brutality of Columbus and his brothers have been exaggerated as part of the Black Legend, a historical tendency towards anti-Spanish sentiment in historical sources dating as far back as the 16th century, which they speculate may continue to taint scholarship into the present day.[176][177][178]

Historian William J. Connell has argued that, while Columbus "brought the entrepreneurial form of slavery to the New World," this "was a phenomenon of the times," further arguing that "we have to be very careful about applying 20th-century understandings of morality to the morality of the 15th century."[179] In a less popular defense of colonization, Spanish ambassador María Jesús Figa López-Palop has argued, "Normally we melded with the cultures in America, we stayed there, we spread our language and culture and religion."[180]

British historian Basil Davidson has dubbed Columbus the "father of the slave trade", citing the fact that the first license to ship African slaves to the Caribbean was issued by the Catholic Monarchs in 1501.[181][additional citation(s) needed]

Depopulation

Around the turn of the 21st century, estimates for the pre-Columbian population of Hispaniola ranged between 250,000 and two million,[106][182][183][u] but genetic analysis published in late 2020 suggests that smaller figures are more likely, perhaps as low as 10,000–50,000 for Hispaniola and Puerto Rico combined.[184][185] Based on the previous figures of a few hundred thousand, some have estimated that a third or more of the natives in Haiti were dead within the first two years of Columbus's governorship.[80][106] Contributors to depopulation included disease, warfare, and harsh enslavement.[186][187][188][189] Indirect evidence suggests that some serious illness may have arrived with the 1,500 colonists who accompanied Columbus's second expedition in 1493.[186] Charles C. Mann writes that "It was as if the suffering these diseases had caused in Eurasia over the past millennia were concentrated into the span of decades."[190] A third of the natives forced to work in gold and silver mines died every six months.[191][192] Within three to six decades, the surviving Arawak population numbered only in the hundreds.[191][106][193] The indigenous population of the Americas overall is thought to have been reduced by about 90% in the century after Columbus's arrival.[194] Within indigenous circles, Columbus is often viewed as a key agent of genocide.[195] Samuel Eliot Morison, a Harvard historian and author of a multivolume biography on Columbus, writes, "The cruel policy initiated by Columbus and pursued by his successors resulted in complete genocide."[196]

According to Noble David Cook, "There were too few Spaniards to have killed the millions who were reported to have died in the first century after Old and New World contact." He instead estimates that the death toll was caused by smallpox,[197] which may have only caused a pandemic after the arrival of Hernán Cortés in 1519.[198][199][200] According to some estimates, smallpox had an 80–90% fatality rate in Native American populations.[201] The natives had no acquired immunity to these new diseases and suffered high fatalities. There is also evidence that they had poor diets and were overworked.[96][202][203] Historian Andrés Reséndez of University of California, Davis, says the available evidence suggests "slavery has emerged as major killer" of the indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550 more so than diseases such as smallpox, influenza and malaria.[204] He says that indigenous populations did not experience a rebound like European populations did following the Black Death because unlike the latter, a large portion of the former were subjected to deadly forced labour in the mines.[192] Historian David Stannard says that their destruction "was neither inadvertent nor inevitable," but the result of microbial pestilence and purposeful genocide working in tandem.[205]

The diseases that devastated the Native Americans came in multiple waves at different times, sometimes as much as centuries apart, which would mean that survivors of one disease may have been killed by others, preventing the population from recovering.[206]

Biographers and historians have a wide range of opinions over Columbus's expertise and experience navigating and captaining ships. One scholar lists some European works ranging from the 1890s to 1980s that support Columbus's experience and skill as among the best in Genoa, while listing some American works over a similar timeframe that portray the explorer as an untrained entrepreneur, having only minor crew or passenger experience prior to his noted journeys.[207] According to Morison, Columbus's success in utilizing the trade winds might owe significantly to luck.[208]

Physical appearance

Contemporary descriptions of Columbus, including those by his son Fernando and Bartolomé de las Casas, describe him as taller than average, with light skin (which was often sunburnt), blue or hazel eyes, high cheekbones and freckled face, an aquiline nose, and blond to reddish hair and beard (until about the age of 30, when it began to whiten).[209][210] Although an abundance of artwork depicts Christopher Columbus, no authentic contemporary portrait is known.[211]

The most iconic image of Columbus is a portrait by Sebastiano del Piombo, which has been reproduced in many textbooks. It agrees with descriptions of Columbus in that it shows a large man with auburn hair, but the painting dates from 1519 and cannot, therefore, have been painted from life. Furthermore, the inscription identifying the subject as Columbus was probably added later, and the face shown differs from other images.[212]

Sometime between 1531 and 1536, Alejo Fernández painted an altarpiece, The Virgin of the Navigators, that includes a depiction of Columbus. The painting was commissioned for a chapel in Seville's Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) and remains there, as the earliest known painting about the voyages of Columbus.[213][214]

At the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, 71 alleged portraits of Columbus were displayed; most did not match contemporary descriptions.[215]

See also

Notes

- ^ In other relevant languages:

- Italian: Cristoforo Colombo [kriˈstɔːforo koˈlombo]

- Ligurian: Cristoffa C(or)ombo [kɾiˈʃtɔffa kuˈɾuŋbu; ˈkuŋbu]

- Spanish: Cristóbal Colón

- Portuguese: Cristóvão Colombo

- Catalan: Cristòfor (or Cristòfol) Colom

- Latin: Christophorus Columbus

- ^ Though the modern Republic of Italy had yet to be established, the Latin equivalent of the term Italian had been in use for natives of the region since antiquity.[4] Most scholars believe that Columbus was born in the Republic of Genoa.[5]

- ^ a b DNA from Columbus's presumed remains in Seville will be used to conduct further ancestral studies, with results expected in 2021.[141]

- ^ In an account of his fourth voyage, Columbus wrote that "Jerusalem and Mount Sion must be rebuilt by Christian hands".[36]

- ^ Ferdinand later claimed credit for being "the principal cause why those islands were discovered."[63]

- ^ a b Felipe Fernández-Armesto points out that Columbus briefly described South America as an unknown continent after seeing the mainland for the first time. Vespucci seems to have modeled his naming of the "new world" after Columbus's description of this discovery. Further, mapmaker Martin Waldseemüller eventually retracted his naming of the continent after Vespucci, seemingly after it came to light that a claim that Vespucci visited the mainland before Columbus had been falsified. In his new map, Waldseemüller labelled the continent as Terra Incognita ('unknown land'), noting that it had been discovered by Columbus.[66]

- ^ This map is based on the premise that Columbus first landed at Plana Cays.[67] The island considered by Samuel Eliot Morison to be the most likely location of first contact[68] is the easternmost land touching the top edge of this image.

- ^ According to Samuel Eliot Morison, San Salvador Island, renamed from Watling's Island in 1925 in the belief that it was Columbus's San Salvador,[77] is the only island fitting the position indicated by Columbus's journal. Other candidates are the Grand Turk, Cat Island, Rum Cay, Samana Cay, or Mayaguana.[68]

- ^ Torres spoke Hebrew and some Arabic; the latter was then believed to be the mother tongue of all languages.[83]

- ^ Omitted from this image, Columbus returned to Guadeloupe at the end of his second voyage before sailing back to Spain.[92]

- ^ The tribute system had all but collapsed by 1497.[105]

- ^ Bobadilla's 48-page report, derived from the testimonies of 23 people who had seen or heard about the treatment meted out by Columbus and his brothers—had originally been lost for centuries, but was rediscovered in 2005 in the Spanish archives in Valladolid. It contained an account of Columbus's seven-year reign as the first governor of the Indies. Consuelo Varela, a Spanish historian, states: "Even those who loved him [Columbus] had to admit the atrocities that had taken place."[118]

- ^ According to Professor Miguel Patella of the University of Granada, who was present the last time Columbus's crypt was opened, these include part of a jaw and an arm, as well as a couple of leg bones and vertebrae.[137]

- ^ This same year, dust collected from these remains was placed in a locket, which was placed inside the stern of a silver model caravel. Two tiny portions of dust from the same source were placed in separate vials.[143]

- ^ Osborne cited the bullet as evidence the remains belonged to Columbus,[144] but its significance is unclear.[142]

- ^ These remains are displayed in their crypt (behind a sheet of glass) once a year on Columbus Day.[145]

- ^ "Columbus's claim to fame isn't that he got there first, it's that he stayed." (Dugard 2005, p. 185)

- ^ On his third voyage, Columbus formulated a new model of the Earth shortly after observing that the North Star is not fixed. Making observations with a quadrant, he "regularly saw the plumb line fall to the same point," instead of moving along as his ship moved. He thought that he had discovered the entrance to Heaven, from which Earth's waters extend, the planet forming a pear shape with the insurmountable "stalk" portion of the pear pointing towards Heaven.[162] In fact, the Earth ever so slightly is pear-shaped, with the "stalk" pointing north.[163]

- ^ Cuneo wrote,

While I was in the boat, I captured a very beautiful Carib woman, whom the said Lord Admiral gave to me. When I had taken her to my cabin she was naked—as was their custom. I was filled with a desire to take my pleasure with her and attempted to satisfy my desire. She was unwilling, and so treated me with her nails that I wished I had never begun. But—to cut a long story short—I then took a piece of rope and whipped her soundly, and she let forth such incredible screams that you would not have believed your ears. Eventually we came to such terms, I assure you, that you would have thought that she had been brought up in a school for whores.[170]

- ^ Author Tony Horwitz notes that this is the first recorded instance of sexuality between a European and Native American.[171]

- ^ Bartolomé de las Casas estimated that there were three to four million Taínos in Hispaniola, and said 500,000 Lucayans were killed in the Bahamas. Most modern historians reject his figures.[183]

References

- ^ Lester, Paul M. (January 1993). "Looks are deceiving: The portraits of Christopher Columbus". Visual Anthropology. 5 (3–4): 211–227. doi:10.1080/08949468.1993.9966590.

- ^ a b Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. – The names Giacomo and Diego are cognates, along with James, all sharing a common origin. See Behind the Name, Mike Campbell, pages Giacomo, Diego, and James. All retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ "Columbus". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Letters 9.23.

- ^ a b Flint, Valerie I.J. (16 May 2021). "Christopher Columbus". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Corinna Praga; Laura Monac (1992). Una Giornata nella Città (in Italian). Genoa: Sagep Editrice. p. 14.

- ^ Alfredo Preste; Alessandro Torti; Remo Viazzi (1997). "Casa di Colombo". Sei itinerari in Portoria (PDF) (in Italian). Genova: Grafiche Frassicomo.

- ^ a b c d Beazley 1911, p. 741.

- ^ Bergreen 2011, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d Encyclopædia Britannica, 1993 ed., Vol. 16, pp. 605ff / Morison, Christopher Columbus, 1955 ed., pp. 14ff

- ^ Rime diverse, Pavia, 1595, p. 117

- ^ Tasso, Torquato (1755). Ra Gerusalemme deliverâ. Genoa: Ra Stamparia de Tarigo. p. 203 (right column, second paragraph). Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ^ Çittara zeneize – Regole d'Ortografia, Genoa, 1745

- ^ Consulta ligure, Vocabolario delle parlate liguri, Sage, 1982, ISBN 88-7058-044-X

- ^ Govan, Fiona (14 October 2009). "Christopher Columbus writings prove he was Spanish, claims study". The Telegraph.

- ^ (in Portuguese) "Armas e Troféus." Revista de História, Heráldica, Genealogia e Arte. 1994, VI serie – Tomo VI, pp. 5–52. Retrieved 21 November 2011.[verification needed]

- ^ Davidson 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Phillips, Jr & Phillips 1992, p. 85.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus". Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2002.. Thomas C. Tirado, PhD Professor History. Millersville University.

- ^ "It is most probable that Columbus visited Bristol, where he was introduced to English commerce with Iceland." Bedini, Silvio A. and David Buisseret (1992). The Christopher Columbus encyclopedia, Volume 1, University of Michigan Press, republished by Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-13-142670-2, p. 175

- ^ Morison 1991, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Anne Paolucci and Henry Paolucci (1992). Columbus, America, and the World, p. 140. "Many Columbists ... have doubted that Columbus could ever have gone to Iceland."

- ^ Freitas, Antonio Maria de (1893). The Wife of Columbus: With Genealogical Tree of the Perestrello and Moniz Families. New York: Stettinger, Lambert & Co.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus (Italian explorer)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Dyson 1991, p. 63.

- ^ Paolo Emilio Taviani, "Beatriz Arana" in The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia, vol. 1, p. 24. New York: Simon and Schuster 1992.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus Biography". Columbus-day.123holiday.net. p. 2. Retrieved 29 July 2009.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Taviani, "Beatriz Arana" in The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia, vol. 1, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Morgan, Edmund S. (October 2009). "Columbus' Confusion About the New World". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Jeakle, Will (11 October 2020). "Six Things You Didn't Know About Christopher Columbus". Forbes. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Charles R. Boxer (1951). The Christian Century in Japan: 1549–1650. University of California Press. p. 2. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Morison 1991, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Journal article: Christopher Columbus. An address delivered before the American Catholic Historical Society

- ^ a b c d Murphy & Coye 2013.

- ^ a b c Delaney, Carol (8 March 2006). "Columbus's Ultimate Goal: Jerusalem" (PDF). Comparative Studies in Society and History. 48 (2): 260–92. doi:10.1017/S0010417506000119. JSTOR 3879352. S2CID 144148903. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2020.

- ^ Sheehan, Kevin Joseph (2008). Iberian Asia: the strategies of Spanish and Portuguese empire building, 1540–1700 (Thesis). OCLC 892835540. ProQuest 304693901.[page needed]

- ^ Hamdani, Abbas (1979). "Columbus and the Recovery of Jerusalem". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 99 (1): 39–48. doi:10.2307/598947. JSTOR 598947.

- ^ Murphy & Coye 2013, p. 244.

- ^ "Mariner's Astrolabe". Institute of Navigation. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian (2001). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Universe. New York: Watson-Guptill. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8230-2512-1.

- ^ Sagan, Carl. Cosmos; the mean circumference of the Earth is 40,041.47 km (24,881 mi).

- ^ Freely, John (2013). Before Galileo: The Birth of Modern Science in Medieval Europe. New York: Abrams. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4683-0850-1.

- ^ "Marco Polo et le Livre des Merveilles", p. 37. ISBN 978-2-35404-007-9

- ^ Morison (1942, pp. 65, 93).

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 68.

- ^ a b Dyson 1991, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c Morison 1991.

- ^ Phillips, Jr & Phillips 1992, p. 110.

- ^ Jensen, De Ladickmar (1992), Renaissance Europe 2nd ed. p. 341

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 59.

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 157.

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 132.

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 314.

- ^ Morison 1991, pp. 198–99.

- ^ Dyson 1991, pp. 67, 69.

- ^ Morison 1991, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Dyson 1991, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Dyson 1991, p. 84.

- ^ Durant, Will The Story of Civilization vol. vi, "The Reformation". Chapter XIII, p. 260.

- ^ Dyson 1991, pp. 86, 92.

- ^ Dyson 1991, p. 92.

- ^ Morrison, Geoffrey (15 October 2015). "Exploring The Alhambra Palace And Fortress In Granada, Spain". Forbes. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Phillips, Jr & Phillips 1992, pp. 131–32.

- ^ Mark McDonald, "Ferdinand Columbus, Renaissance Collector (1488–1539)", 2005, British Museum Press, ISBN 978-0-7141-2644-9

- ^ Cohen, Jonathan. "The Naming of America". Umc.sunysb.edu. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2007). Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America (1st ed.). New York: Random House. pp. 143–44, 186–87. ISBN 978-1-4000-6281-2. OCLC 608082366.

- ^ Pickering, Keith A. (August 1994). "Columbus's Plana landfall: Evidence for the Plana Cays as Columbus's 'San Salvador'" (PDF). DIO – the International Journal of Scientific History. 4 (1): 13–32. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ a b Morison 1991, p. 228.

- ^ a b Dyson 1991, p. 102.

- ^ "The Original Niña". The Niña & Pinta. British Virgin Islands: The Columbus Foundation. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Phillips Jr & Phillips 1993, pp. 146–47.

- ^ Nicholls, Steve (2009). Paradise Found: Nature in America at the Time of Discovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-226-58340-2.

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 226.

- ^ Lopez, (1990, p. 14); Columbus & Toscanelli (2010, p. 35)

- ^ Lopez, (1990, p. 15)

- ^ Bergreen 2011, p. 99.

- ^ William D. Phillips Jr., 'Columbus, Christopher', in David Buisseret (ed.), The Oxford Companion to World Exploration, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, online edition 2012).

- ^ Robert H. Fuson, ed., The Log of Christopher Columbus, Tab Books, 1992, International Marine Publishing, ISBN 0-87742-316-4.

- ^ Hoxie, Frederick (1996). Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 568. ISBN 978-0-395-66921-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zinn 2003, pp. 1–22

- ^ Columbus (1991, p. 87). Or "these people are very simple as regards the use of arms … for with fifty men they can all be subjugated and made to do what is required of them." (Columbus & Toscanelli, 2010, p. 41)

- ^ Keith A. Pickering. "The First Voyage of Columbus". Archived from the original on 7 March 2012.

- ^ a b Morison 1991, p. 145.

- ^ Maclean, Frances (January 2008). "The Lost Fort of Columbus". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ^ Fuson, Robert. The Log of Christopher Columbus (Camden, International Marine, 1987) 173.

- ^ Yewell, John; Chris Dodge (1992). Confronting Columbus: An Anthology. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-89950-696-8. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Markham, Clements R. (1893). The Journal of Christopher Columbus. London: Hakluyt Society. pp. 159–160. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Oliver Dunn and James Kelly. The Diario of Christopher Columbus's First Voyage to America (London: University of Oklahoma Press), 333–343.

- ^ Catz, Rebecca (1 January 1990). "Columbus in the Azores". Portuguese Studies. 6: 17–23. JSTOR 41104900.

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 381.

- ^ Diffie, Bailey Wallys (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580. Winius, George D. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-8166-0782-6. OCLC 3488742.

- ^ Morison 1991, pp. 498–501.

- ^ Morison 1991, pp. 423–27.

- ^ Antonio de la Cova. "The Spanish Conquest of the Tainos". Latin American Studies. Dr. Antonio Rafael de la Cova. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "Teeth Of Columbus's Crew Flesh Out Tale Of New World Discovery". ScienceDaily. 20 March 2009.

- ^ a b Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8263-2871-7. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ Alfred W. Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, Westport, 1972, pp. 39, 45, 47.

- ^ Yeager, Timothy J. (3 March 2009). "Encomienda or Slavery? The Spanish Crown's Choice of Labor Organization in Sixteenth-Century Spanish America". The Journal of Economic History. 55 (4): 842–859. doi:10.1017/S0022050700042182. JSTOR 2123819.

- ^ Lyle N. McAlister (1984). Spain and Portugal in the New World, 1492–1700. University of Minnesota Press. p. 164. ISBN 0-8166-1218-8.

- ^ a b Lane, Kris (8 October 2015). "Five myths about Christopher Columbus". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Morison 1991, pp. 482–85.

- ^ Olson, Julius E. and Edward G. Bourne (editors). "The Northmen, Columbus and Cabot, 985–1503", in The Voyages of the Northmen; The Voyages of Columbus and of John Cabot. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1906), pp. 369–383.

- ^ Stannard, David E. (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Koning, Hans. Columbus, His Enterprise: Exploding the Myth. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1976: 83-83.

- ^ Deagan, Kathleen A.; Cruxent, José María (2008). Columbus's Outpost Among the Taínos: Spain and America at La Isabela, 1493–1498. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-300-13389-9.

- ^ a b c d e Dyson 1991, pp. 183, 190.

- ^ Cohen, Rhaina; Penman, Maggie; Boyle, Tara; Vedantam, Shankar (20 November 2017). "An American Secret: The Untold Story Of Native American Enslavement". NPR.org. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2007). Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America. New York: Random House. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-4000-6281-2.

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 497.

- ^ Christopher Minster, "The Third Voyage of Christopher Columbus"

- ^ Joseph 1838, p. 124

- ^ a b Zerubavel, Eviatar (2003). Terra Cognita: The Mental Discovery of America. Transaction Publishers. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-7658-0987-2.

- ^ Bergreen 2011, p. 249.

- ^ Bergreen 2011, p. 258.

- ^ "Christopher Columbus Voyage on Tripline". www.tripline.net. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Brink, Christopher. Christopher Columbus: Controversial Explorer of the Americas. p. 78.

- ^ Bergreen 2011, pp. 276–77.

- ^ a b c Giles Tremlett (7 August 2006). "Lost document reveals Columbus as tyrant of the Caribbean". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "Columbus Controversy". A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ Bergreen 2011, p. 281.

- ^ Noble, David Cook. "Nicolás de Ovando" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol.4, p. 254. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ^ Bergreen 2011, pp. 288–89, 302–3.

- ^ Dugard 2005, pp. 130–31.

- ^ a b Bergreen 2011, p. 330.

- ^ Bergreen 2011, p. 332.

- ^ Joy Jakim, The First Americans: Prehistory – 1600 A History of US Oxford University Press 2005[page needed]

- ^ Clayton J., Drees, The Late Medieval Age of Crisis and Renewal: 1300–1500 a Biographical Dictionary, 2001, p. 511

- ^ Kadir, Djelal (1992). Columbus and the Ends of the Earth: Europe's Prophetic Rhetoric as Conquering Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-520-91133-8.

- ^ McDonald, Mark P. (2005). Ferdinand Columbus: Renaissance Collector. London: British Museum Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7141-2644-9. OCLC 56964320.

- ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Sevilla". Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Christopher Columbus Suffered From a Fatal Form of Arthritis" (Press release). University of Maryland School of Medicine. 6 May 2005. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018.

- ^ Hoenig, Leonard J. (1 February 1992). "The Arthritis of Christopher Columbus". Archives of Internal Medicine. 152 (2): 274–277. doi:10.1001/archinte.1992.00400140028008. PMID 1472175.

- ^ Dyson 1991, p. 194.

- ^ a b c d e Dyson 1991, p. 196.

- ^ Thacher, John Boyd; Morison, Samuel Eliot (1903). "Monastery of Las Cuevos". Christopher Columbus: His life, his work, his remains as revealed by original printed and manuscript records, together with an essay on Peter Martyr of Anghera and Bartolomé de las Casas, the first historians of America. New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons: The Knickerbocker Press. pp. 515–521. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ History Today August 2003

- ^ "Columbus Unearthed". Expedition Unknown. Travel Channel. 9 December 2015. Event occurs at 37.

- ^ Tremlett, Giles (11 August 2004). "Young bones lay Columbus myth to rest". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ a b "DNA verifies Columbus' remains in Spain". MSNBC. Associated Press. 20 May 2006. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ a b Álvarez-Cubero, M.J.; Mtnez.-Gonzalez, L.J.; Saiz, M.; Álvarez, J.C.; Lorente, J.A. (June 2010). "Nuevas aplicaciones en identificación genética" [New applications in genetic identification]. Cuadernos de Medicina Forense (in Spanish). 16 (1–2). doi:10.4321/S1135-76062010000100002.

- ^ "Countdown begins to discover where Columbus came from". AP News. 19 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ a b Bergreen 2011, pp. 363–64.

- ^ Thacher, John Boyd (1904). Christopher Columbus: his life, his works, his remains: as revealed by original printed and manuscript records, together with an essay on Peter Martyr of Anghera and Bartolomé de las Casas, the first historians of America. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 570–73.

- ^ a b "Columbus Buried In San Domingo?". Evening Star. 17 July 1913. p. 11. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Horwitz 2008, pp. 89–90, 92.

- ^ a b Burmila, Edward (9 October 2017). "The Invention of Christopher Columbus, American Hero". The Nation.

- ^ "Bird's-Eye View of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893". World Digital Library. 1893. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ "Columbian Exposition Souvenir Sheets", Arago: people, postage & the post, National Postal Museum online, viewed 18 April 2014.

- ^ "Columbus Monuments Pages: Boalsburg". Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ Boivin, Nicole; Fuller, Dorian Q; Crowther, Alison (September 2012). "Old World globalization and the Columbian exchange: comparison and contrast". World Archaeology. 44 (3): 452–469. doi:10.1080/00438243.2012.729404. JSTOR 42003541. S2CID 3285807.

- ^ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (Spring 2010), "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas" (PDF), Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24 (2): 163–188, doi:10.1257/jep.24.2.163

- ^ "Christopher Columbus | Biography, Nationality, Voyages, Ships, Route, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Columbian Exchange – The Old World Meets The New World". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Curran, James Watson (1939). Here was Vinland: The Great Lakes Region of America. Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario: Sault Daily Star. p. 207.

- ^ "History – Leif Erikson (11th century)". BBC. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Little, Becky (11 October 2015). "Why Do We Celebrate Columbus Day and Not Leif Erikson Day?". National Geographic. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Thomas F. McIlwraith; Edward K. Muller (2001). North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7425-0019-8.

- ^ Phillips, Jr & Phillips 1992, p. 227.

- ^ Sale, Kirkpatrick (1991) [1990]. The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy. New York: Plume. pp. 204–209. ISBN 0-452-26669-6. OCLC 23940970.

- ^ Boller, Paul F (1995). Not So!: Popular Myths about America from Columbus to Clinton. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509186-1.

- ^ Hannam, James (18 May 2010). "Science Versus Christianity?". Patheos.com. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ a b Bergreen 2011, p. 244.

- ^ Tyson, Neil deGrasse (2014) [2007]. Death By Black Hole: And Other Cosmic Quandaries (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-393-06224-3. OCLC 70265574.

- ^ Jeffrey Burton Russell (1991). Inventing the Flat Earth: Columbus and modern historians. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-95904-3.

- ^ Brito, Christopher (25 September 2020). "Dozens of Christopher Columbus statues have been removed since June". CBS News. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Bigelow, Bill (1992). "Once upon a Genocide: Christopher Columbus in Children's Literature". Social Justice. 19 (2): 106–121..

- ^ Jack Weatherford (20 April 2001). "Examining the reputation of Christopher Columbus". Hartford-hwp.com. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ "Pre-Columbian Hispaniola – Arawak/Taino Indians". Hartford-hwp.com. 15 September 2001. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ Morison 1991, p. 417.

- ^ Cohen, J.M. (1969). The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus. NY: Penguin. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-14-044217-5.

- ^ Horwitz 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Irving, Washington (1881). Life and voyages of Columbus, v.1-2. 1. G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 52.

- ^ "$15 in 1881 → 2021". Inflation Calculator. U.S. Official Inflation Data, Alioth Finance. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ Koning, Hans (1976). Columbus. Monthly Review Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-85345-600-1. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ Varela, Consuelo; Aguirre, Isabel (2006). "La venta de esclavos" [The sale of slaves]. La caída de Cristóbal Colón: el juicio de Bobadilla [The fall of Christopher Columbus: the Bobadilla trial] (in Spanish). Marcial Pons Historia. pp. 111–118. ISBN 978-84-96467-28-6.

- ^ Hanke, Lewis (1 February 1971). "A Modest Proposal for a Moratorium on Grand Generalizations: Some Thoughts on the Black Legend". Hispanic American Historical Review. 51 (1): 112–127. doi:10.1215/00182168-51.1.112. JSTOR 2512616.

- ^ Keen, Benjamin (1 November 1969). "The Black Legend Revisited: Assumptions and Realities". Hispanic American Historical Review. 49 (4): 703–719. doi:10.1215/00182168-49.4.703. JSTOR 2511162.

- ^ Keen, Benjamin (1 May 1971). "The White Legend Revisited: A Reply to Professor Hanke's 'Modest Proposal'". Hispanic American Historical Review. 51 (2): 336–355. doi:10.1215/00182168-51.2.336. JSTOR 2512479.

- ^ Fusco, Mary Ann Castronovo (8 October 2000). "In Person; In Defense Of Columbus". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Horwitz 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Bigelow, Bill (10 October 2015). "Columbus Day must be abolished". The Ottawa Herald. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ Zinn 2003, p. 5.

- ^ a b Keegan, William F., "Destruction of the Taino" in Archaeology. January/February 1992, pp. 51–56.

- ^ Fernandes, D.M.; Sirak, K.A.; Ringbauer, H.; et al. (23 December 2020). "A genetic history of the pre-contact Caribbean". Nature. 590 (7844): 103–110. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2. PMC 7864882. PMID 33361817.

- ^ Dutchen, Stephanie (23 December 2020). "Ancient DNA shines light on Caribbean history, prehistory". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ a b Horwitz 2008.

- ^ Alfred W. Crosby, The Columbian Exchange Westport, 1972, p. 47.

- ^ Abbot 2010.

- ^ Chrisp 2006, p. 34.

- ^ Mann, Charles C. (2011). 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 12.

- ^ a b Hickel, Jason (2018). The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions. Windmill Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-78609-003-4.

- ^ a b Treuer, David (13 May 2016). "The new book 'The Other Slavery' will make you rethink American history". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Crosby (1972), The Columbian Exchange, p. 45.

- ^ Koch, Alexander; Brierley, Chris; Maslin, Mark; Lewis, Simon (1 March 2019). "Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492". Quaternary Science Reviews. 207: 13–36. Bibcode:2019QSRv..207...13K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.12.004.

- ^ Schuman, H.; Schwartz, B.; D'Arcy, H. (28 February 2005). "Elite Revisionists and Popular Beliefs: Christopher Columbus, Hero or Villain?" (PDF). Public Opinion Quarterly. 69 (1): 2–29. doi:10.1093/poq/nfi001. S2CID 145447081. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2020.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1955). Christopher Columbus, Mariner. Little Brown & Co (T); First edition. ISBN 978-0-316-58356-5.

- ^ Cook, Noble David (13 February 1998). Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge University Press. pp. 9–14. ISBN 978-0-521-62730-6.

- ^ Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Ježek Z, Ladnyi ID (1988). "The History of Smallpox and its Spread Around the World" (PDF). Smallpox and its eradication. History of International Public Health. 6. Geneva: World Health Organization. p. 236. hdl:10665/39485. ISBN 978-92-4-156110-5. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Oliver, José R. (2009). Caciques and Cemí idols : the web spun by Taíno rulers between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-8173-5515-9. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "Deadly Diseases: Epidemics throughout history". CNN. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Arthur C. Aufderheide, Conrado Rodríguez-Martín, Odin Langsjoen (1998). The Cambridge encyclopedia of human paleopathology. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-521-55203-6

- ^ Alfred W. Crosby, The Columbian Exchange, Westport, 1972, pp. 39, 47.

- ^ Martin, Debra L; Goodman, Alan H (2002). "Health conditions before Columbus: paleopathology of native North Americans". Western Journal of Medicine. 176 (1): 65–68. doi:10.1136/ewjm.176.1.65. PMC 1071659. PMID 11788545.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-547-64098-3.

- ^ David E. Stannard (1993). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.