Belarus

Coordinates: 53°N 27°E / 53°N 27°E

Republic of Belarus

| |

|---|---|

Anthem: Дзяржаўны Гімн Рэспублікі Беларусь Dziaržaŭny Himn Respubliki Bielaruś (English: "State Anthem of Belarus") | |

| Capital and largest city | Minsk 53°55′N 27°33′E / 53.917°N 27.550°E |

| Official languages | |

| Recognized minority language | |

| Ethnic groups (2019) |

|

| Religion (2011)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Belarusian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Alexander Lukashenko (disputed)[2][3] | |

| Roman Golovchenko[4] | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Council of the Republic | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from Russia | |

• Declared | 25 March 1918 |

• From the USSR | 10 December 1991 |

• Recognized | 26 December 1991 |

| 15 March 1994 | |

| 17 October 2004 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 207,595 km2 (80,153 sq mi) (84th) |

• Water (%) | 1.4% (2.830 km2 or 1.093 sq mi)b |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 9,349,645 (96th) |

• 2019 census | |

• Density | 45.8/km2 (118.6/sq mi) (142nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | low |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 53rd |

| Currency | Belarusian ruble (BYN) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK[8]) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +375 |

| ISO 3166 code | BY |

| Internet TLD | |

Website belarus.by | |

| |

Belarus,[a] officially the Republic of Belarus,[b] is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Covering an area of 207,600 square kilometres (80,200 sq mi) and with a population of 9.3 million, Belarus is the thirteenth-largest and the twentieth-most populous country in Europe. The country is administratively divided into seven regions. Minsk is the capital and largest city.

Until the 20th century, different states at various times controlled the lands of modern-day Belarus, including Kievan Rus', the Principality of Polotsk, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Russian Empire. In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in 1917, different states arose competing for legitimacy amidst the Civil War, ultimately ending in the rise of the Byelorussian SSR, which became a founding constituent republic of the Soviet Union in 1922. After the Polish-Soviet War, Belarus lost almost half of its territory to Poland. Much of the borders of Belarus took their modern shape in 1939, when some lands of the Second Polish Republic were reintegrated into it after the Soviet invasion of Poland, and were finalized after World War II.[10][11][12] During World War II, military operations devastated Belarus, which lost about a quarter of its population and half of its economic resources.[13] The republic was redeveloped in the post-war years. In 1945, the Byelorussian SSR became a founding member of the United Nations, along with the Soviet Union.

The parliament of the republic proclaimed the sovereignty of Belarus on 27 July 1990, and during the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Belarus declared independence on 25 August 1991.[14] Following the adoption of a new constitution in 1994, Alexander Lukashenko was elected Belarus's first president in the country's first and only free election post-independence, serving as president ever since.[15] Lukashenko's government is widely considered to be authoritarian and human rights groups consider human rights in the country to be poor.[16][17] Belarus is the only country in Europe officially using the death penalty. Lukashenko has continued a number of Soviet-era policies, such as state ownership of large sections of the economy. In 2000, Belarus and Russia signed a treaty for greater cooperation, forming the Union State.

Belarus is a developing country ranking very high in the Human Development Index. It has been a member of the United Nations since its founding and a member of the CIS, the CSTO, the EAEU, and the Non-Aligned Movement. It has shown no aspirations for joining the European Union but nevertheless maintains a bilateral relationship with the Union, and likewise participates in two EU projects: the Eastern Partnership and the Baku Initiative.

Etymology

The name Belarus is closely related with the term Belaya Rus', i.e., White Rus'. There are several claims to the origin of the name White Rus'.[18] An ethno-religious theory suggests that the name used to describe the part of old Ruthenian lands within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that had been populated mostly by Slavs who had been Christianized early, as opposed to Black Ruthenia, which was predominantly inhabited by pagan Balts.[19] An alternative explanation for the name comments on the white clothing worn by the local Slavic population.[18][20] A third theory suggests that the old Rus' lands that were not conquered by the Tatars (i.e., Polotsk, Vitebsk and Mogilev) had been referred to as White Rus'.[18] A fourth theory suggests that the color white was associated with the west, and Belarus was the western part of Rus in the 9th-13th centuries.[21]

The name Rus is often conflated with its Latin forms Russia and Ruthenia, thus Belarus is often referred to as White Russia or White Ruthenia. The name first appeared in German and Latin medieval literature; the chronicles of Jan of Czarnków mention the imprisonment of Lithuanian grand duke Jogaila and his mother at "Albae Russiae, Poloczk dicto" in 1381.[22] The first known use of White Russia to refer to Belarus was in the late-16th century by Englishman Sir Jerome Horsey, who was known for his close contacts with the Russian Royal Court.[23] During the 17th century, the Russian tsars used White Rus to describe the lands added from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[24]

The term Belorussia (Russian: Белору́ссия, the latter part similar but spelled and stressed differently from Росси́я, Russia) first rose in the days of the Russian Empire, and the Russian Tsar was usually styled "the Tsar of All the Russias", as Russia or the Russian Empire was formed by three parts of Russia—the Great, Little, and White.[25] This asserted that the territories are all Russian and all the peoples are also Russian; in the case of the Belarusians, they were variants of the Russian people.[26]

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the term White Russia caused some confusion, as it was also the name of the military force that opposed the red Bolsheviks.[27] During the period of the Byelorussian SSR, the term Byelorussia was embraced as part of a national consciousness. In western Belarus under Polish control, Byelorussia became commonly used in the regions of Białystok and Grodno during the interwar period.[28]

The term Byelorussia (its names in other languages such as English being based on the Russian form) was only used officially until 1991. Officially, the full name of the country is Republic of Belarus (Рэспубліка Беларусь, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus ![]() listen (help·info)).[29][30] In Russia, the usage of Belorussia still is very common.[31] In Lithuanian, besides Baltarusija (White Russia), Belarus is also called Gudija.[32][33] The ethimology of the word Gudija is not clear. By one of the hypothesis the word derives from the Old Prussian name Gudwa, which, in turn, is related to the form Żudwa, which is a distorted version of Sudwa, Sudovia. Sudovia, in its turn, is one of the names of Yotvingians. Another hypothesis connects the word with Gothic Kingdom that occupied parts of territory of modern Belarus and Ukraine in 4th and 5th centuries. The self-naming of Goths was Gutans and Gytos that is close to Gudija. Yet another hypothesis is based that Gudija in Lithuanian means the other and may refer to any people who do not speak common Lithuanian language.[34]

listen (help·info)).[29][30] In Russia, the usage of Belorussia still is very common.[31] In Lithuanian, besides Baltarusija (White Russia), Belarus is also called Gudija.[32][33] The ethimology of the word Gudija is not clear. By one of the hypothesis the word derives from the Old Prussian name Gudwa, which, in turn, is related to the form Żudwa, which is a distorted version of Sudwa, Sudovia. Sudovia, in its turn, is one of the names of Yotvingians. Another hypothesis connects the word with Gothic Kingdom that occupied parts of territory of modern Belarus and Ukraine in 4th and 5th centuries. The self-naming of Goths was Gutans and Gytos that is close to Gudija. Yet another hypothesis is based that Gudija in Lithuanian means the other and may refer to any people who do not speak common Lithuanian language.[34]

History

Early history

From 5000 to 2000 BC, Bandkeramik cultures predominated. In addition, remains from the Dnieper-Donets culture were found in Belarus and parts of Ukraine.[35] Cimmerians and other pastoralists roamed through the area by 1,000 BC, and by 500 AD, Slavs had taken up residence, which was circumscribed by the Scythians who roamed its outskirts. Invaders from Asia, among whom were the Huns and Avars, swept through c. 400–600 AD, but were unable to dislodge the Slavic presence.[36]

The region that is now Belarus was first settled by Baltic tribes in the 3rd century. Around the 5th century, the area was taken over by Slavic tribes. The takeover was partially due to the lack of military coordination of the Balts but the gradual assimilation of the Balts into Slavic culture was peaceful in nature.[37]

Kievan Rus'

In the 9th century the territory of modern Belarus became part of Kievan Rus', a vast East Slavic state ruled by the Rurikid dynasty. Upon the death of Kievan Rus' ruler Yaroslav I the Wise, the state split into independent principalities.[38] Many early Rus' principalities were virtually razed or severely affected by a major Mongol invasion in the 13th century, but the lands of modern-day Belarus avoided the brunt of the invasion and eventually joined the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[39] There are no sources of military seizure, but the annals affirm the alliance and united foreign policy of Polotsk and Lithuania for decades.[40] Trying to avoid the Tatar Yoke, the Principality of Minsk sought protection from Lithuanian princes further north and in 1242, Minsk became a part of the expanding Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Incorporation into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania resulted in an economic, political and ethno-cultural unification of Belarusian lands.[41] Of the principalities held by the Duchy, nine of them were settled by a population that would eventually become the Belarusians.[42] During this time, the Duchy was involved in several military campaigns, including fighting on the side of Poland against the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410; the joint victory allowed the Duchy to control the northwestern borderlands of Eastern Europe.[43]

The Muscovites, led by Ivan III of Moscow, began military campaigns in 1486 in an attempt to incorporate the former lands of Kievan Rus', specifically the territories of modern-day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.[44]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

On 2 February 1386, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland were joined in a personal union through a marriage of their rulers.[45] This union set in motion the developments that eventually resulted in the formation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, created in 1569 by the Union of Lublin.[46][47]

The Lithuanian nobles were forced to go for rapprochement because of the threat coming from Muscovy. To strengthen the independence in the format of the union, three editions of the Statutes of Lithuania were issued in the 16th century. The third Article of the Statute establishes that all lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania will be eternally in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and never enter as a part of other states. It allowed the right to own land within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to only its own families. Anyone from outside the Duchy gaining rights to a property would actually own it only after swearing allegiance to the Grand Duke of Lithuania. These articles were aimed to defend the rights of the nobility of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania nobility against Polish, Prussian and other aristocracy of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[citation needed]

In the years following the union, the process of gradual Polonization of both Lithuanians and Ruthenians gained steady momentum. In culture and social life, both the Polish language and Catholicism became dominant, and in 1696, Polish replaced Ruthenian as the official language—with the Ruthenian language being banned from administrative use.[48] However, the Ruthenian peasants continued to speak their own language and remained faithful to the Belarusian Greek Catholic Church. Statutes were initially issued in the Ruthenian language alone and later also in Polish. Around 1840 the Statutes were banned by the Russian tsar following the November Uprising. Modern Ukrainian lands used it until 1860s.[citation needed]

Russian Empire

The union between Poland and Lithuania ended in 1795 with the Third Partition of Poland by Imperial Russia, Prussia, and Austria.[49] The Belarusian territories acquired by the Russian Empire under the reign of Catherine II[50] were included into the Belarusian Governorate (Russian: Белорусское генерал-губернаторство) in 1796 and held until their occupation by the German Empire during World War I.[51]

Under Nicholas I and Alexander III the national cultures were repressed. Policies of Polonization[52] changed by Russification,[53] which included the return to Orthodox Christianity of Belarusian Uniates. Belarusian language was banned in schools while in neighboring Samogitia primary school education with Samogitian literacy was allowed.[54]

In a Russification drive in the 1840s, Nicholas I prohibited use of the Belarusian language in public schools, campaigned against Belarusian publications and tried to pressure those who had converted to Catholicism under the Poles to reconvert to the Orthodox faith. In 1863, economic and cultural pressure exploded in a revolt, led by Konstanty Kalinowski (also known as Kastus). After the failed revolt, the Russian government reintroduced the use of Cyrillic to Belarusian in 1864 and no documents in Belarusian were permitted by the Russian government until 1905.[55]

During the negotiations of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Belarus first declared independence under German occupation on 25 March 1918, forming the Belarusian People's Republic.[56][57] Immediately afterwards, the Polish–Soviet War ignited, and the territory of Belarus was divided between Poland and Soviet Russia.[58] The Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic exists as a government in exile ever since then; in fact, it is currently the world's longest serving government in exile.[59]

Early states and interwar period

The Belarusian People's Republic was the first attempt to create an independent Belarusian state under name "Belarus". Despite significant efforts the state ceased to exist, primarily because the territory was continually dominated by the German Imperial Army and the Imperial Russian Army in World War I, and then the Bolshevik Red Army. It existed from only 1918 to 1919 but created prerequisites for the formation of the state idea around the name "Belarus". The choice of the name was probably based on the fact that the educated core of the newly formed government was educated in the tsardom universities, with a corresponding education around the ideology of West-Russianism.[60]

The Republic of Central Lithuania was a short-lived political entity, which was the last attempt to restore Lithuania in the historical confederacy state (it was also supposed to create Lithuania Upper and Lithuania Lower). The republic was created in 1920 following the staged rebellion of soldiers of the 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division of the Polish Army under Lucjan Żeligowski. Centered on the historical capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Vilna (Lithuanian: Vilnius, Polish: Wilno), for 18 months the entity served as a buffer state between Poland, upon which it depended, and Lithuania, which claimed the area.[61] After a variety of delays, a disputed election took place on 8 January 1922, and the territory was annexed to Poland. Żeligowski later in his memoir which was published in London in 1943 condemned the annexation of the Republic by Poland, as well as the policy of closing Belarusian schools and general disregard of Marshal Józef Piłsudski's confederation plans by Polish ally.[62] Years earlier interrogation report of 19-year-old revolutionary Pilsudski of 10 March 1887 indicated that he called himself a "Belarusian nobleman".[63]

In 1919 a part of Belarus under Russian rule emerged as the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (Byelorussian SSR). Soon thereafter it merged to form the Lithuanian-Byelorussian SSR. The contested lands were divided between Poland and the Soviet Union after the war ended in 1921, and the Byelorussian SSR became a founding member of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1922.[56][64] In the 1920s and 1930s, Soviet agricultural and economic policies, including collectivization and five-year plans for the national economy, led to famine and political repression.[65]

The western part of modern Belarus remained part of the Second Polish Republic.[66][67][68] After an early period of liberalization, tensions between increasingly nationalistic Polish government and various increasingly separatist ethnic minorities started to grow, and the Belarusian minority was no exception.[69][70] The polonization drive was inspired and influenced by the Polish National Democracy, led by Roman Dmowski, who advocated refusing Belarusians and Ukrainians the right for a free national development.[71] A Belarusian organization, the Belarusian Peasants' and Workers' Union, was banned in 1927, and opposition to Polish government was met with state repressions.[69][70] Nonetheless compared to the (larger) Ukrainian minority, Belarusians were much less politically aware and active, and thus suffered fewer repressions than the Ukrainians.[69][70] In 1935, after the death of Józef Piłsudski, a new wave of repressions was released upon the minorities, with many Orthodox churches and Belarusian schools being closed.[69][70] Use of the Belarusian language was discouraged.[72] Belarusian leadership was sent to Bereza Kartuska prison.[73]

Second World War and later Soviet period

In 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union invaded and occupied Poland, marking the beginning of World War II. The Soviets invaded and annexed much of eastern Poland, which had been part of the country since the Peace of Riga two decades earlier. Much of the northern section of this area was added to the Byelorussian SSR, and now constitutes West Belarus.[10][11][12][74] The Soviet-controlled Byelorussian People's Council officially took control of the territories, whose populations consisted of a mixture of Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians and Jews, on 28 October 1939 in Białystok. Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. The defense of Brest Fortress was the first major battle of Operation Barbarossa.

Statistically, the Byelorussian SSR was the hardest-hit Soviet republic in World War II; it remained in Nazi hands until 1944. During that time, Germany destroyed 209 out of 290 cities in the republic, 85% of the republic's industry, and more than one million buildings.[13] The German Generalplan Ost called for the extermination, expulsion, or enslavement of most or all Belarusians for the purpose of providing more living space in the East for Germans.[75] Most of Western Belarus became part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland in 1941, but in 1943 the German authorities allowed local collaborators to set up a client state, the Belarusian Central Rada.[76]

The German occupation in 1941–1944 and war on the Eastern Front devastated Belarus. More than 1.6 million civilians and 620,000 Belarusian Red Army soldiers died,[77] and the country lost about 25% of its population.[78] The Jewish population of Belarus was devastated during the Holocaust and never recovered.[13][79][80][81] The population of Belarus did not regain its pre-war level until 1971.[79]

After the war, Belarus was among the 51 founding member states of the United Nations Charter and as such it was allowed an additional vote at the UN, on top of the Soviet Union's vote. Vigorous postwar reconstruction promptly followed the end of the war and the Byelorussian SSR became a major center of manufacturing in the western USSR, creating jobs and attracting ethnic Russians.[citation needed] The borders of the Byelorussian SSR and Poland were redrawn, in accord with the 1919-proposed Curzon Line.[51]

Joseph Stalin implemented a policy of Sovietization to isolate the Byelorussian SSR from Western influences.[79] This policy involved sending Russians from various parts of the Soviet Union and placing them in key positions in the Byelorussian SSR government. After Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev continued his predecessor's cultural hegemony program, stating, "The sooner we all start speaking Russian, the faster we shall build communism."[79]

Soviet Belarusian communist politician Andrei Gromyko, who served as Soviet foreign minister (1957–1985) and as Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (1985–1988), was responsible for many top decisions on Soviet foreign policy until he was replaced by Eduard Shevardnadze.[82] In 1986, the Byelorussian SSR was contaminated with most (70%) of the nuclear fallout from the explosion at the Chernobyl power plant located 16 km beyond the border in the neighboring Ukrainian SSR.[83][84]

In June 1988, the archaeologist and leader of the Christian Conservative Party of the BPF Zyanon Paznyak discovered mass graves of victims executed in 1937–41 at Kurapaty, near Minsk.[83] Some nationalists contend that this discovery is proof that the Soviet government was trying to erase the Belarusian people, causing Belarusian nationalists to seek independence.[85]

Independence

In March 1990, elections for seats in the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian SSR took place. Though the pro-independence Belarusian Popular Front took only 10% of the seats, the populace was content with the selection of the delegates.[86] Belarus declared itself sovereign on 27 July 1990 by issuing the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic.[87]

With the support of the Communist Party, the country's name was changed to the Republic of Belarus on 25 August 1991.[86] Stanislav Shushkevich, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of Belarus, met with Boris Yeltsin of Russia and Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine on 8 December 1991 in Belavezhskaya Pushcha to formally declare the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the formation of the Commonwealth of Independent States.[86]

A national constitution was adopted in March 1994 in which the functions of prime minister were given to the President of Belarus, Two-round elections for the presidency on (24 June 1994 and 10 July 1994)[88] catapulted the formerly unknown Alexander Lukashenko into national prominence. He garnered 45% of the vote in the first round and 80%[86] in the second, defeating Vyacheslav Kebich who received 14% of the vote. Lukashenko was re-elected in 2001, in 2006, in 2010 and again in 2015. Western governments,[89] Amnesty International,[17] and Human Rights Watch[90] have criticized Lukashenko's authoritarian style of government.[clarification needed]

Since 2014, following years of embrace of Russian influence in the country, Lukashenko has pressed a revival of Belarusian identity. For the first time, he delivered a speech in Belarusian (rather than Russian, which most Belarusians speak as their primary language), in which he said, "We are not Russian—we are Belarusians", and later encouraged the use of Belarusian. Trade disputes, a border dispute, and a much relaxed official attitude to dissident voices are all part of a weakening of the longtime warm relationship with Russia.[91][better source needed]

In 2019, Lukashenko had bilateral talks in Sochi with Russian president Vladimir Putin and declared that their two countries "could unite tomorrow, no problem."[92] An idea backed by Putin for years, observers have labeled the potential plan a scheme by Putin to remain in power beyond 2024.[93] However, political scientist Mikhail Vinogradov explained that "Lukashenko will play tough to the public while trying to look weak in front of Putin," and the Carnegie Moscow Center's Artyom Shraibman suggested that "Moscow will most likely fail to find its base among Belarusians."[94]

Mass protests erupted across the country following the disputed 2020 Belarusian presidential election,[95] in which Lukashenko sought a sixth term in office.[96] Russian and EU leaders warned of any external interference in Belarus's internal affairs.[97][98][99] The Lithuanian government has allotted a residence for main opposition candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and other members of the Belarusian opposition in Vilnius, Lithuania.[100][101][102] Poland also supports opposition.[103][104] Following the disputed election, Lukashenko is not recognized by the European Union and United States as the legitimate president of Belarus.[105][106] The European Union and the United States imposed sanctions against Belarus because of the rigged election and political oppression during to the ongoing protests in the country.[107]

Geography

Belarus lies between latitudes 51° and 57° N, and longitudes 23° and 33° E. Its extension from north to south is 560 km (350 mi), from west to east is 650 km (400 mi).[108] It is landlocked, relatively flat, and contains large tracts of marshy land.[109] About 40% of Belarus is covered by forests.[110][111] The country lies within two ecoregions: Sarmatic mixed forests and Central European mixed forests.[112]

Many streams and 11,000 lakes are found in Belarus.[109] Three major rivers run through the country: the Neman, the Pripyat, and the Dnieper. The Neman flows westward towards the Baltic sea and the Pripyat flows eastward to the Dnieper; the Dnieper flows southward towards the Black Sea.[113]

The highest point is Dzyarzhynskaya Hara (Dzyarzhynsk Hill) at 345 metres (1,132 ft), and the lowest point is on the Neman River at 90 m (295 ft).[109] The average elevation of Belarus is 160 m (525 ft) above sea level.[114] The climate features mild to cold winters, with January minimum temperatures ranging from −4 °C (24.8 °F) in southwest (Brest) to −8 °C (17.6 °F) in northeast (Vitebsk), and cool and moist summers with an average temperature of 18 °C (64.4 °F).[115] Belarus has an average annual rainfall of 550 to 700 mm (21.7 to 27.6 in).[115] The country is in the transitional zone between continental climates and maritime climates.[109]

Natural resources include peat deposits, small quantities of oil and natural gas, granite, dolomite (limestone), marl, chalk, sand, gravel, and clay.[109] About 70% of the radiation from neighboring Ukraine's 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster entered Belarusian territory, and about a fifth of Belarusian land (principally farmland and forests in the southeastern regions) was affected by radiation fallout.[116] The United Nations and other agencies have aimed to reduce the level of radiation in affected areas, especially through the use of caesium binders and rapeseed cultivation, which are meant to decrease soil levels of caesium-137.[117][118]

Belarus borders five countries: Latvia to the north, Lithuania to the northwest, Poland to the west, Russia to the north and the east, and Ukraine to the south. Treaties in 1995 and 1996 demarcated Belarus's borders with Latvia and Lithuania, and Belarus ratified a 1997 treaty establishing the Belarus-Ukraine border in 2009.[119] Belarus and Lithuania ratified final border demarcation documents in February 2007.[120]

Governance

Belarus is a presidential republic, governed by a president and the National Assembly. The term for each presidency is five years. Under the 1994 constitution, the president could serve for only two terms as president, but a change in the constitution in 2004 eliminated term limits.[121] Alexander Lukashenko has been the president of Belarus since 1994. In 1996, Lukashenko called for a controversial vote to extend the presidential term from five to seven years, and as a result the election that was supposed to occur in 1999 was pushed back to 2001. The referendum on the extension was denounced as a "fantastic" fake by the chief electoral officer, Viktar Hanchar, who was removed from the office for official matters only during the campaign.[122] The National Assembly is a bicameral parliament comprising the 110-member House of Representatives (the lower house) and the 64-member Council of the Republic (the upper house).[123]

The House of Representatives has the power to appoint the prime minister, make constitutional amendments, call for a vote of confidence on the prime minister, and make suggestions on foreign and domestic policy.[124] The Council of the Republic has the power to select various government officials, conduct an impeachment trial of the president, and accept or reject the bills passed by the House of Representatives. Each chamber has the ability to veto any law passed by local officials if it is contrary to the constitution.[125]

The government includes a Council of Ministers, headed by the prime minister and five deputy prime ministers.[126] The members of this council need not be members of the legislature and are appointed by the president. The judiciary comprises the Supreme Court and specialized courts such as the Constitutional Court, which deals with specific issues related to constitutional and business law. The judges of national courts are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Council of the Republic. For criminal cases, the highest court of appeal is the Supreme Court. The Belarusian Constitution forbids the use of special extrajudicial courts.[125]

In the 2012 parliamentary election, 105 of the 110 members elected to the House of Representatives were not affiliated with any political party. The Communist Party of Belarus won 3 seats, and the Agrarian Party and Republican Party of Labour and Justice, one each.[127] Most non-partisans represent a wide scope of social organizations such as workers' collectives, public associations, and civil society organizations, similar to the composition of the Soviet legislature.[128]

Elections

Belarus has often been described as "Europe's last dictatorship" by some media outlets, politicians and authors due to its authoritarian government;[129][130][131][132] Lukashenko has described himself as having an "authoritarian ruling style".[121] The Council of Europe removed Belarus from its observer status since 1997 as a response for election irregularities in the November 1996 constitutional referendum and parliament by-elections.[133][134] Re-admission of the country into the council is dependent on the completion of benchmarks set by the council, including the improvement of human rights, rule of law, and democracy.[135]

Neither the pro-Lukashenko parties, such as the Belarusian Socialist Sporting Party and the Republican Party of Labour and Justice, nor the People's Coalition 5 Plus opposition parties, such as the Belarusian People's Front and the United Civil Party of Belarus, won any seats in the 2004 elections. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) ruled that the elections were unfair because opposition candidates were arbitrarily denied registration and the election process was designed to favor the ruling party.[136]

In the 2006 presidential election, Lukashenko was opposed by Alaksandar Milinkievič, who represented a coalition of opposition parties, and by Alaksandar Kazulin of the Social Democrats. Kazulin was detained and beaten by police during protests surrounding the All Belarusian People's Assembly. Lukashenko won the election with 80% of the vote; the Russian Federation and the CIS deemed the vote open and fair[137] while the OSCE and other organizations called the election unfair.[138]

After the December completion of the 2010 presidential election, Lukashenko was elected to a fourth straight term with nearly 80% of the vote in elections. The runner-up opposition leader Andrei Sannikov received less than 3% of the vote; independent observers criticized the election as fraudulent. When opposition protesters took to the streets in Minsk, many people, including most rival presidential candidates, were beaten and arrested by the state militia.[139] Many of the candidates, including Sannikov, were sentenced to prison or house arrest for terms which are mainly and typically over four years.[140][141] Six months later amid an unprecedented economic crisis, activists utilized social networking to initiate a fresh round of protests characterized by wordless hand-clapping.[142]

In the 2020 presidential election the official result was 80% for Lukashenko again. The election process and events afterwards have been criticized by representatives of many other countries.

Foreign relations

The Byelorussian SSR was one of the two Soviet republics that joined the United Nations along with the Ukrainian SSR as one of the original 51 members in 1945.[143] Belarus and Russia have been close trading partners and diplomatic allies since the breakup of the Soviet Union. Belarus is dependent on Russia for imports of raw materials and for its export market.[144]

The union of Russia and Belarus, a supranational confederation, was established in a 1996–99 series of treaties that called for monetary union, equal rights, single citizenship, and a common foreign and defense policy. However, the future of the union has been placed in doubt because of Belarus's repeated delays of monetary union, the lack of a referendum date for the draft constitution, and a dispute over the petroleum trade.[144][145] Belarus was a founding member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).[146] Belarus has trade agreements with several European Union member states (despite other member states' travel ban on Lukashenko and top officials),[147] including neighboring Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland.[148] Travel bans imposed by the European Union have been lifted in the past in order to allow Lukashenko to attend diplomatic meetings and also to engage his government and opposition groups in dialogue.[149]

Bilateral relations with the United States are strained; the United States had not had an ambassador in Minsk since 2007 and Belarus never had an ambassador in Washington since 2008.[150][151] Diplomatic relations remained tense, and in 2004, the United States passed the Belarus Democracy Act, which authorized funding for anti-government Belarusian NGOs, and prohibited loans to the Belarusian government, except for humanitarian purposes.[152] Sino-Belarusian relations have improved,[153] strengthened by the visit of President Lukashenko to China in October 2005.[154] Belarus also has strong ties with Syria,[155] considered a key partner in the Middle East.[156] In addition to the CIS, Belarus is a member of the Eurasian Economic Community, the Collective Security Treaty Organisation,[148] the international Non-Aligned Movement since 1998,[157] and the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). As an OSCE member state, Belarus's international commitments are subject to monitoring under the mandate of the U.S. Helsinki Commission.[158] Belarus is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer in economic and geopolitical terms.[159]

Military

Major General Andrei Ravkov heads the Ministry of Defence,[160] and Alexander Lukashenko (as president) serves as Commander-in-Chief.[125] The armed forces were formed in 1992 using parts of the former Soviet Armed Forces on the new republic's territory. The transformation of the ex-Soviet forces into the Armed Forces of Belarus, which was completed in 1997, reduced the number of its soldiers by 30,000 and restructured its leadership and military formations.[161]

Most of Belarus's service members are conscripts, who serve for 12 months if they have higher education or 18 months if they do not.[162] Demographic decreases in the Belarusians of conscription age have increased the importance of contract soldiers, who numbered 12,000 in 2001.[163] In 2005, about 1.4% of Belarus's gross domestic product was devoted to military expenditure.[164]

Belarus has not expressed a desire to join NATO but has participated in the Individual Partnership Program since 1997,[165] and Belarus provides refueling and airspace support for the ISAF mission in Afghanistan.[166] Belarus first began to cooperate with NATO upon signing documents to participate in their Partnership for Peace Program in 1995.[167] However, Belarus cannot join NATO because it is a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation. Tensions between NATO and Belarus peaked after the March 2006 presidential election in Belarus.[168]

Human rights and corruption

Belarus's Democracy Index rating is the lowest in Europe, the country is labelled as "not free" by Freedom House, as "repressed" in the Index of Economic Freedom, and is rated as the worst country for press freedom in Europe in the 2013–2014 Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, which ranks Belarus 157th out of 180 nations.[169] The Belarusian government is also criticized for human rights violations and its persecution of non-governmental organisations, independent journalists, national minorities, and opposition politicians.[17][90] Lukashenko announced a new law in 2014 that will prohibit kolkhoz workers (around 9% of total work force) from leaving their jobs at will—a change of job and living location will require permission from governors. The law was compared with serfdom by Lukashenko himself.[170][171] Similar regulations were introduced for the forestry industry in 2012.[172] Belarus is the only European country still using capital punishment having carried out executions in 2011.[173]

The judicial system in Belarus lacks independence and is subject to political interference.[174] Corrupt practices such as bribery often took place during tender processes, and whistleblower protection and national ombudsman are lacking in Belarus's anti-corruption system.[175] However, there is a political will to fight against corruption in the government, and the government has made some progress in combating corruption, such as minimizing tax regulations in order to improve transparency in the tax office.[176]

On September 1, 2020 the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights declared that its experts received reports of 450 documented cases of torture and ill-treatment of people who were arrested during the protests following the presidential election. The experts also received reports of violence against women and children, including sexual abuse and rape with rubber batons.[177] At least three detainees suffered injuries indicative of sexual violence in Okrestino prison in Minsk or on the way there. The victims were hospitalized with intramuscular bleeding of the rectum, anal fissure and bleeding, and damage to the mucous membrane of the rectum.[178] In an interview from September 2020 Lukashenko claimed that detainees faked their bruises, saying, "Some of the girls there had their butts painted in blue".[179]

Administrative divisions

Belarus is divided into six regions (Belarusian: вобласць, Russian: о́бласть), which are named after the cities that serve as their administrative centers: Brest, Gomel, Grodno, Mogilev, Minsk, and Vitebsk.[180] Each region has a provincial legislative authority, called a region council (Belarusian: абласны Савет Дэпутатаў, Russian: областно́й Сове́т Депутатов), which is elected by its residents, and a provincial executive authority called a region administration (Belarusian: абласны выканаўчы камітэт, Russian: областно́й исполнительный комите́т), whose chairman is appointed by the president.[181] Regions are further subdivided into raions, commonly translated as districts (Belarusian: раён, Russian: район).[180] Each raion has its own legislative authority, or raion council, (Belarusian: раённы Савет Дэпутатаў, Russian: районный Сове́т Депутатов) elected by its residents, and an executive authority or raion administration appointed by higher executive powers. The six regions are divided into 118 raions.[110] The city of Minsk is split into nine districts and enjoys special status as the nation's capital.[182] It is run by an executive committee and has been granted a charter of self-rule.[183]

Economy

In 2019 the share of manufacturing in GDP was 31%, over two thirds of this amount falls on manufacturing industries. The number of people employed in industry is 34.7% of the working population.[184] The growth rate is much lower than for the economy as a whole—about 2.2% in 2021. At the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Belarus was one of the world's most industrially developed states by percentage of GDP as well as the richest CIS member-state.[185] In 2015, 39.3% of Belarusians were employed by state-controlled companies, 57.2% were employed by private companies (in which the government has a 21.1% stake) and 3.5% were employed by foreign companies.[186] The country relies on Russia for various imports, including petroleum.[187][188] Important agricultural products include potatoes and cattle byproducts, including meat.[189] In 1994, Belarus's main exports included heavy machinery (especially tractors), agricultural products, and energy products.[190] Economically, Belarus involved itself in the CIS, Eurasian Economic Community, and Union with Russia.[191]

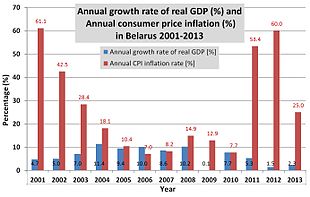

In the 1990s, however, industrial production plunged due to decreases in imports, investment, and demand for Belarusian products from its trading partners.[192] GDP only began to rise in 1996;[193] the country was the fastest-recovering former Soviet republic in the terms of its economy.[194] In 2006, GDP amounted to US$83.1 billion in purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars (estimate), or about $8,100 per capita.[189] In 2005, GDP increased by 9.9%; the inflation rate averaged 9.5%.[189]

Since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, under Lukashenko's leadership, Belarus has maintained government control over key industries and eschewed the large-scale privatizations seen in other former Soviet republics.[195]

In 2006, Belarus's largest trading partner was Russia, accounting for nearly half of total trade, with the European Union the next largest trading partner, with nearly a third of foreign trade.[196][197] As of 2015[update], 38% of Belarusian exported goods go to Russia and 56% of imported goods come from Russia.[186]

Due to its failure to protect labor rights, including passing laws forbidding unemployment or working outside of state-controlled sectors,[198] Belarus lost its EU Generalized System of Preferences status on 21 June 2007, which raised tariff rates to their prior most favored nation levels.[197] Belarus applied to become a member of the World Trade Organization in 1993.[199]

The labor force consists of more than four million people, among whom women hold slightly more jobs than men.[186] In 2005, nearly a quarter of the population was employed by industrial factories. Employment is also high in agriculture, manufacturing sales, trading goods, and education. The unemployment rate, according to government statistics, was 1.5% in 2005. There were 679,000 unemployed Belarusians, two-thirds of whom were women. The unemployment rate has been in decline since 2003, and the overall rate of employment is the highest since statistics were first compiled in 1995.[186]

The currency of Belarus is the Belarusian ruble. The currency was introduced in May 1992 to replace the Soviet ruble and it has undergone redenomination twice since then. The first coins of the Republic of Belarus were issued on 27 December 1996.[200] The ruble was reintroduced with new values in 2000 and has been in use ever since.[201] As part of the Union of Russia and Belarus, both states have discussed using a single currency along the same lines as the Euro. This led to a proposal that the Belarusian ruble be discontinued in favor of the Russian ruble (RUB), starting as early as 1 January 2008. The National Bank of Belarus abandoned pegging the Belarusian ruble to the Russian ruble in August 2007.[202]

A new currency, the new Belarusian ruble (ISO 4217 code: BYN)[203] was introduced in July 2016, replacing the Belarusian ruble in a rate of 1:10,000 (10,000 old rubles = 1 new ruble). From 1 July until 31 December 2016, the old and new currencies were in parallel circulation and series 2000 notes and coins can be exchanged for series 2009 from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2021.[203] This redenomination can be considered an effort to fight the high inflation rate.[204][205]

The banking system of Belarus consists of two levels: Central Bank (National Bank of the Republic of Belarus) and 25 commercial banks.[206] On 23 May 2011, the Belarusian ruble depreciated 56% against the United States dollar. The depreciation was even steeper on the black market and financial collapse seemed imminent as citizens rushed to exchange their rubles for dollars, euros, durable goods, and canned goods.[207] On 1 June 2011, Belarus requested an economic rescue package from the International Monetary Fund.[208][209]

Demographics

According to the 2019 census the population was 9.41 million[210] with ethnic Belarusians constituting 84.9% of Belarus's total population.[210] Minority groups include: Russians (7.5%), Poles (3.1%), and Ukrainians (1.7%).[210] Belarus has a population density of about 50 people per square kilometer (127 per sq mi); 70% of its total population is concentrated in urban areas.[211] Minsk, the nation's capital and largest city, was home to 1,937,900 residents in 2015[update].[212] Gomel, with a population of 481,000, is the second-largest city and serves as the capital of the Homiel Voblast. Other large cities are Mogilev (365,100), Vitebsk (342,400), Hrodna (314,800) and Brest (298,300).[213]

Like many other Eastern European countries, Belarus has a negative population growth rate and a negative natural growth rate. In 2007, Belarus's population declined by 0.41% and its fertility rate was 1.22,[214] well below the replacement rate. Its net migration rate is +0.38 per 1,000, indicating that Belarus experiences slightly more immigration than emigration. As of 2015[update], 69.9% of Belarus's population is aged 14 to 64; 15.5% is under 14, and 14.6% is 65 or older. Its population is also aging; the median age of 30–34 is estimated to rise to between 60 and 64 in 2050.[215] There are about 0.87 males per female in Belarus.[214] The average life expectancy is 72.15 (66.53 years for men and 78.1 years for women).[214] Over 99% of Belarusians aged 15 and older are literate.[214]

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Minsk  Homyel |

1 | Minsk | Minsk Voblast | 1,992,685 |  Mahilyow  Vitsyebsk | ||||

| 2 | Homyel | Homyel Voblast | 536,938 | ||||||

| 3 | Mahilyow | Mahilou Voblast | 383,313 | ||||||

| 4 | Vitsyebsk | Vitsebsk Voblast | 378,459 | ||||||

| 5 | Hrodna | Hrodna Voblast | 373,547 | ||||||

| 6 | Brest | Brest Voblast | 350,616 | ||||||

| 7 | Babruysk | Mahilou Voblast | 216,793 | ||||||

| 8 | Baranavichy | Brest Voblast | 179,000 | ||||||

| 9 | Barysaw | Minsk Voblast | 142,681 | ||||||

| 10 | Pinsk | Brest Voblast | 137,960 | ||||||

Religion and languages

According to the census of November 2011, 58.9% of all Belarusians adhered to some kind of religion; out of those, Eastern Orthodoxy (Belarusian Exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church) made up about 82%.[1] Roman Catholicism is practiced mostly in the western regions, and there are also different denominations of Protestantism.[216][217] Minorities also practice Greek Catholicism, Judaism, Islam and Neopaganism. Overall, 48.3% of the population is Orthodox Christian, 41.1% is not religious, 7.1% is Catholic and 3.3% follows other religions.[1]

Belarus's Catholic minority is concentrated in the western part of the country, especially around Hrodna, is made up of a mixture of Belarusians and the country's Polish and Lithuanian minorities.[218] President Lukashenko has stated that Orthodox and Catholic believers are the "two main confessions in our country".[219]

Belarus was once a major center of European Jews, with 10% of the population being Jewish. But since the mid-20th century, the number of Jews has been reduced by the Holocaust, deportation, and emigration, so that today it is a very small minority of less than one percent.[220] The Lipka Tatars, numbering over 15,000, are predominantly Muslims. According to Article 16 of the Constitution, Belarus has no official religion. While the freedom of worship is granted in the same article, religious organizations deemed harmful to the government or social order can be prohibited.[180]

Belarus's two official languages are Russian and Belarusian;[221] Russian is the most common language used at home, used by 70% of the population, while Belarusian, the official first language, is spoken at home by 23%.[222] Minorities also speak Polish, Ukrainian and Eastern Yiddish.[223] Belarusian, although not as widely used as Russian, is the mother tongue of 53.2% of the population, whereas Russian is the mother tongue of only 41.5%.[222]

Culture

Arts and literature

The Belarusian government sponsors annual cultural festivals such as the Slavianski Bazaar in Vitebsk,[224] which showcases Belarusian performers, artists, writers, musicians, and actors. Several state holidays, such as Independence Day and Victory Day, draw big crowds and often include displays such as fireworks and military parades, especially in Vitebsk and Minsk.[225] The government's Ministry of Culture finances events promoting Belarusian arts and culture both inside and outside the country.

Belarusian literature[226] began with 11th- to 13th-century religious scripture, such as the 12th-century poetry of Cyril of Turaw.[227]

By the 16th century, Polotsk resident Francysk Skaryna translated the Bible into Belarusian. It was published in Prague and Vilnius sometime between 1517 and 1525, making it the first book printed in Belarus or anywhere in Eastern Europe.[228] The modern era of Belarusian literature began in the late 19th century; one prominent writer was Yanka Kupala. Many Belarusian writers of the time, such as Uładzimir Žyłka, Kazimir Svayak, Yakub Kolas, Źmitrok Biadula, and Maksim Haretski, wrote for Nasha Niva, a Belarusian-language paper published that was previously published in Vilnius but now is published in Minsk.[229]

After Belarus was incorporated into the Soviet Union, the Soviet government took control of the Republic's cultural affairs. At first, a policy of "Belarusianization" was followed in the newly formed Byelorussian SSR. This policy was reversed in the 1930s, and the majority of prominent Belarusian intellectuals and nationalist advocates were either exiled or killed in Stalinist purges.[230] The free development of literature occurred only in Polish-held territory until Soviet occupation in 1939. Several poets and authors went into exile after the Nazi occupation of Belarus and would not return until the 1960s.[228]

The last major revival of Belarusian literature occurred in the 1960s with novels published by Vasil Bykaŭ and Uladzimir Karatkievich. An influential author who devoted his work to awakening the awareness of the catastrophes the country has suffered, was Ales Adamovich. He was named by Svetlana Alexievich, the Belarusian winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature 2015, as "her main teacher, who helped her to find a path of her own".[231]

Music in Belarus largely comprises a rich tradition of folk and religious music. The country's folk music traditions can be traced back to the times of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the 19th century, Polish composer Stanisław Moniuszko composed operas and chamber music pieces while living in Minsk. During his stay, he worked with Belarusian poet Vintsent Dunin-Martsinkyevich and created the opera Sialanka (Peasant Woman). At the end of the 19th century, major Belarusian cities formed their own opera and ballet companies. The ballet Nightingale by M. Kroshner was composed during the Soviet era and became the first Belarusian ballet showcased at the National Academic Vialiki Ballet Theatre in Minsk.[232]

After the Second World War, music focused on the hardships of the Belarusian people or on those who took up arms in defense of the homeland. During this period, Anatoly Bogatyrev, creator of the opera In Polesye Virgin Forest, served as the "tutor" of Belarusian composers.[233] The National Academic Theatre of Ballet in Minsk was awarded the Benois de la Dance Prize in 1996 as the top ballet company in the world.[233] Rock music has become increasingly popular in recent years, though the Belarusian government has attempted to limit the amount of foreign music aired on the radio in favor of traditional Belarusian music. Since 2004, Belarus has been sending artists to the Eurovision Song Contest.[234][235]

Marc Chagall was born in Liozna (near Vitebsk) in 1887. He spent the World War I years in Soviet Belarus, becoming one of the country's most distinguished artists and a member of the modernist avant-garde and was a founder of the Vitebsk Arts College.[236][237]

Dress

The traditional Belarusian dress originates from the Kievan Rus' period. Due to the cool climate, clothes were designed to conserve body heat and were usually made from flax or wool. They were decorated with ornate patterns influenced by the neighboring cultures: Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Russians, and other European nations. Each region of Belarus has developed specific design patterns.[238] One ornamental pattern common in early dresses currently decorates the hoist of the Belarusian national flag, adopted in a disputed referendum in 1995.[239]

Cuisine

Belarusian cuisine consists mainly of vegetables, meat (particularly pork), and bread. Foods are usually either slowly cooked or stewed. Typically, Belarusians eat a light breakfast and two hearty meals later in the day. Wheat and rye breads are consumed in Belarus, but rye is more plentiful because conditions are too harsh for growing wheat. To show hospitality, a host traditionally presents an offering of bread and salt when greeting a guest or visitor.[240]

Sport

This article or section appears to be slanted towards recent events. (November 2020) |

Belarus has competed in the Olympic Games since the 1994 Winter Olympics as an independent nation. Receiving heavy sponsorship from the government, ice hockey is the nation's second most popular sport after football. The national football team has never qualified for a major tournament; however, BATE Borisov has played in the Champions League. The national hockey team finished fourth at the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics following a memorable upset win over Sweden in the quarterfinals, and regularly competes in the World Championships, often making the quarterfinals. Numerous Belarusian players are present in the Kontinental Hockey League in Eurasia, particularly for Belarusian club HC Dinamo Minsk, and several have also played in the National Hockey League in North America. Darya Domracheva is a leading biathlete whose honours include three gold medals at the 2014 Winter Olympics.[241]

Tennis player Victoria Azarenka became the first Belarusian to win a Grand Slam singles title at the Australian Open in 2012.[242] She also won the gold medal in mixed doubles at the 2012 Summer Olympics with Max Mirnyi, who holds ten Grand Slam titles in doubles.

Other notable Belarusian sportspeople include cyclist Vasil Kiryienka, who won the 2015 Road World Time Trial Championship, and middle-distance runner Maryna Arzamasava, who won the gold medal in the 800m at the 2015 World Championships in Athletics. Andrei Arlovski, who was born in Babruysk, Byelorussian SSR, is a current UFC fighter and the former UFC heavyweight champion of the world.

Belarus is also known for its strong rhythmic gymnasts. Noticeable gymnasts include Inna Zhukova, who earned silver at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Liubov Charkashyna, who earned bronze at the 2012 London Olympics and Melitina Staniouta, Bronze All-Around Medalist of the 2015 World Championships. The Belorussian senior group earned bronze at the 2012 London Olympics.

Telecommunications

- Country code: .by

The state telecom monopoly, Beltelecom, holds the exclusive interconnection with Internet providers outside of Belarus. Beltelecom owns all the backbone channels that linked to the Lattelecom, TEO LT, Tata Communications (former Teleglobe), Synterra, Rostelecom, Transtelekom and MTS ISPs. Beltelecom is the only operator licensed to provide commercial VoIP services in Belarus.[243]

World Heritage Sites

Belarus has four UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites: the Mir Castle Complex, the Nesvizh Castle, the Belovezhskaya Pushcha (shared with Poland), and the Struve Geodetic Arc (shared with nine other countries).[244]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Religion and denominations in the Republic of Belarus" (PDF). Mfa.gov.by. November 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Belarus leader Lukashenko holds secret inauguration amid continuing protests". france24.com. 23 September 2020.

- ^ "Belarus: Mass protests after Lukashenko secretly sworn in". BBC News. 23 September 2020.

- ^ "Lukashenko appoints new government". eng.belta.by. 19 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "GINI index (World Bank estimate) – Belarus". World Bank. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Time Zone & Clock Changes in Minsk, Belarus". www.timeanddate.com.

- ^ "Icann Адобрыла Заяўку Беларусі На Дэлегаванне Дамена Першага Ўзроўню З Падтрымкай Алфавітаў Нацыянальных Моў.Бел". Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ a b Abdelal, Rawi (2001). National purpose in the world economy: post-Soviet states in comparative perspective. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3879-0.

- ^ a b Taylor & Francis Group (2004). Europa World Year, Book 1. Europa publications. ISBN 978-1-85743-254-1.

- ^ a b

- Клоков В. Я. Великий освободительный поход Красной Армии. (Освобождение Западной Украины и Западной Белоруссии).-Воронеж, 1940.

- Минаев В. Западная Белоруссия и Западная Украина под гнетом панской Польши.—М., 1939.

- Трайнин И.Национальное и социальное освобождение Западной Украины и Западной Белоруссии.—М., 1939.—80 с.

- Гiсторыя Беларусі. Том пяты.—Мінск, 2006.—с. 449–474

- ^ a b c Axell, Albert (2002). Russia's Heroes, 1941–45. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 247. ISBN 0-7867-1011-X.

- ^ "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Profile: Europe's last dictator? BBC News, 10 September 2001

- ^ Levitsky, Steven; Way, Lucan A. (2010). "The Evolution of Post-SovietCompetitive Authoritarianism". Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Problems of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 203. ISBN 9781139491488. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

Unlike his predecessor, Lukashenka consolidated authoritarian rule. He censored state media, closed Belarus's only independent radio station [...].

- ^ a b c "Human rights by country – Belarus". Amnesty International. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Zaprudnik 1993, p. 2

- ^ Аб паходжанні назваў Белая і Чорная Русь (Eng. "About the Origins of the Names of White and Black Ruthenia"), Язэп Юхо (Joseph Juho), 1956.

- ^ Minahan 1998, p. 35

- ^ "Why Is Belarus called White Russia | Belarus Travel". 5 April 2016.

- ^ Vauchez, Dobson & Lapidge 2001, p. 163

- ^ Bely, Alies (2000). The chronicle of the White Russia: an essay on the history of one geographical name. Minsk, Belarus: Encyclopedix. ISBN 985-6599-12-1.

- ^ Plokhy 2001, p. 327

- ^ Philip G. Roeder (2011). Where Nation-States Come From: Institutional Change in the Age of Nationalism. ISBN 978-0-691-13467-3.

- ^ Fishman, Joshua; Garcia, Ofelia (2011). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts. ISBN 978-0-19-983799-1.

- ^ Richmond 1995, p. 260

- ^ Ioffe, Grigory (2008). Understanding Belarus and How Western Foreign Policy Misses the Mark. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7425-5558-7.

- ^ "Law of the Republic of Belarus – About the name of the Republic of Belarus" (in Russian). Pravo – Law of the Republic of Belarus. 19 September 1991. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ^ "Belarus – Government". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ ""Беларусь" vs "Белоруссия": ставим точку в вопросе". Onliner (in Russian). 26 February 2014.

- ^ ""Gudija" ar "Baltarusija"?". State Commission of the Lithuanian Language (in Lithuanian).

- ^ "Lithuania Refuses to Call Belarus as "Belarusia"". Telegraf.by. 16 April 2010.

- ^ Dziarnovič, Aleh (2013). Gudas as a Historical Name of Belarusians in the Lithuanian Language: 'Goths' or 'Barbarians'? inBelarus and its Neighbors: Historical Perceptions and Political Constructs. International Conference Papers. Warsaw: Uczelnia Łazarskiego. pp. 56–68.

- ^ Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert (2008). A Dictionary of Archaeology. Wiley. pp. 203–04. ISBN 978-0-470-75196-1.

- ^ John Haywood, Historical Atlas, Ancient and Classical World (1998).

- ^ Zaprudnik 1993, p. 7

- ^ Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0-521-86403-8.

- ^ Robinson, Charles Henry (1917). The Conversion of Europe. Longmans, Green. pp. 491–92.

- ^ Michell, Robert; Shakhmaton, A.A; Forbes, Nevill; Beazley, C. Raymond (Charles Raymond) (1914). The chronicle of Novgorod, 1016–1471. London, Offices of the society. p. 41.

- ^ Ermalovich, Mikola (1991). Pa sliadakh adnago mifa (Tracing one Myth). Minsk: Navuka i tekhnika. ISBN 978-5-343-00876-0.

- ^ Zaprudnik 1993, p. 27

- ^ Lerski, George Jan; Aleksander Gieysztor (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. Greenwood Press. pp. 181–82. ISBN 0-313-26007-9.

- ^ Nowak, Andrzej (1 January 1997). "The Russo-Polish Historical Confrontation". Sarmatian Review XVII. Rice University. Archived from the original on 18 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Rowell, S.C. (2005). "Baltic Europe". In Jones, Michael (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History (Vol. 6). Cambridge University Press. p. 710. ISBN 0-521-36290-3.

- ^ Lukowski, Jerzy; Zawadzki, Hubert (2001). A Concise History of Poland (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9780521559171.

- ^ Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (1999). A History of Russia (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195121797.

- ^ "Belarusian": UCLA Language Materials Project Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, ucla.edu; accessed 4 March 2016.

- ^ Scheuch, E.K.; David Sciulli (2000). Societies, Corporations and the Nation State. BRILL. p. 187. ISBN 90-04-11664-8.

- ^ Birgerson 2002, p. 101

- ^ a b Olson, Pappas & Pappas 1994, p. 95

- ^ (in Russian) Воссоединение униатов и исторические судьбы Белорусского народа (Vossoyedineniye uniatov i istoričeskiye sud'bi Belorusskogo naroda), Pravoslavie portal

- ^ Żytko, Russian policy ..., p551.

- ^ Иван Петрович Корнилов (1908). Русское дєло в Сєверо-Западном крає: материиалы для историии Виленскаго учебнаго округа преимущественно в Муравьевскую эпоху (in Russian). Тип. А.С. Суворина.

- ^ D. Marples (1996). Belarus: From Soviet Rule to Nuclear Catastrophe. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-230-37831-5.

- ^ a b Birgerson 2002, pp. 105–106

- ^ Ioffe, Grigory (25 February 2008). Understanding Belarus and How Western Foreign Policy Misses the Mark. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7425-5558-7.

- ^ Timothy Snyder (2002). The Reconstruction of Nations. Yale University Press. p. 282. ISBN 9780300128413.

- ^ "Europe's Last Dictatorship Is Opposed by the Oldest Exiled Government in the World". 26 January 2016.

- ^ Vitali Silitski, Jr.; Jan Zaprudnik (7 April 2010). The A to Z of Belarus. Scarecrow Press. pp. 308–. ISBN 978-1-4617-3174-0.

- ^ Rauch, Georg von (1974). "The Early Stages of Independence". In Gerald Onn (ed.). The Baltic States: Years of Independence – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, 1917–40. C. Hurst & Co. pp. 100–102. ISBN 0-903983-00-1.

- ^ Żeligowski, Lucjan (1943). Zapomniane prawdy (PDF) (in Polish). F. Mildner & Sons.

- ^ "25 years ago it was announced that Joseph Pilsudski – Belarusian (Photo)" (in Belarusian).

- ^ Marples, David (1999). Belarus: A Denationalized Nation. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 90-5702-343-1.

- ^ "Belarus history". Official website of the Republic of Belarus. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Sorge, Arndt (2005). The global and the local: understanding the dialectics of business systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191535345.

- ^ Minahan 1998, p. 37.

- ^ Nick Baron; Peter Gatrell (10 August 2004). "War, Population Displacement and State Formation in the Russian Borderlands 1914–1924". Homelands. Anthem Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-84331-385-4. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d Norman Davies, God's Playground (Polish edition), second tome, p.512-513

- ^ a b c d "Stosunki polsko-białoruskie pod okupacją sowiecką (1939–1941)". Archived from the original on 23 June 2008.

- ^ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Piłsudski camp [Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego] (in Polish). Białystok. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- ^ Bieder, H. (2000): Konfession, Ethnie und Sprache in Weißrußland im 20. Jahrhundert. In: Zeitschrift für Slawistik 45 (2000), 200–214.

- ^ Ivan S. Lubachko. Belorussia under Soviet Rule, 1917–1957 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1972), 137

- ^ Andrew Wilson (2011). Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship. ISBN 978-0-300-13435-3.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. p. 160. ISBN 0465002390

- ^ (German) Dallin, Alexander (1958). Deutsche Herrschaft in Russland, 1941–1945: Eine Studie über Besatzungspolitik, pp. 234–236. Droste Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf.

- ^ Vadim Erlikman. Poteri narodonaseleniia v XX veke : spravochnik. Moscow 2004. ISBN 5-93165-107-1 pp. 23–35

- ^ "This Chart Shows The Astounding Devastation Of World War II". Business Insider. 30 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d Fedor, Helen (1995). "Belarus – Stalin and Russification". Belarus: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- ^ "Потери гражданского населения". function.mil.ru. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "Great Patriotic War in Belarus | Belarus.by". www.belarus.by. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Remnick, David (4 July 1989). "Andrei Gromyko Dies, Was Soviet Diplomat for 50 Years". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Fedor, Helen (1995). "Belarus- Perestroika". Belarus: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ^ "Belarus: Five things you may not know about the country". BBC. 11 August 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Birgerson 2002, p. 99

- ^ a b c d Fedor, Helen (1995). "Belarus – Prelude to Independence". Belarus: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "History, Belarus". Belarus.by. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "World Factbook: Belarus" (TXT). Central Intelligence Agency. 20 October 1994. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- ^ Foreign Affairs; International Trade Canada (25 September 2012). "Standing up for Free and Fair Elections in Belarus". Government of Canada. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Essential Background – Belarus". Human Rights Watch. 2005. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- ^ The Strange Death of Russia's Closest Alliance, Global Voices, 21 February 2017

- ^ "Belarus Ready to 'Unite' With Russia, Lukashenko Says". The Moscow Times. 15 February 2019. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Brennan, David (16 February 2019). "Russia May Absorb Belarus: 'We're Ready to Unite,' President Says". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Sherwin, Emily (13 February 2019). "Could Russia and Belarus trade oil for national sovereignty?". DW. Moscow. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Belarus's Protests Aren't Particularly Anti-Putin". Foreign Policy. 19 August 2020.

- ^ "Protests in Belarus continue despite challenger's departure". Associated Press. 11 August 2020.

- ^ "EU leaders to warn Russia against Belarus interference". EUobserver. 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Putin warns western leaders over 'meddling' in Belarus". Financial Times. 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Russian FM in Syria, meets Assad in first visit since 2012". Associated Press. 7 September 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Belarus asks Lithuania to extradite opposition leader Tsikhanouskaya". Euronews. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Lithuania to Belarus: 'Rather watch hell freeze over' than deliver Tsikhanouskaya". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Headquarters of Tsikhanouskaya, Coordination Council and National Anti-Crisis Management". Voice of Belarus. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Belarus protests: Why Poland is backing the opposition". BBC News. 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Belarus opposition leader: Foreign mediation may be needed". Associated Press. 9 September 2020.

- ^ "El Pais interview with HR/VP Borrell: "Lukashenko is like Maduro. We do not recognize him but we must deal with him"". eeas.europa.eu. 24 August 2020.

- ^ Dave Lawler, U.S. no longer recognizes Lukashenko as legitimate president of Belarus, Axios (24 September 2020).

- ^ "U.S., EU Sanction Belarus in Coordinated Western Action". The Wall Street Journal. 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Coordinates of the extreme points of the state frontier. Main Geographic Characteristics of the Republic of Belarus". Land of Ancestors. the Scientific and Production State Republican Unitary Enterprise "National Cadastre Agency" of the State Property Committee of the Republic of Belarus. 2011. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Belarus – Geography". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ a b "Key Facts". Press Service of the President of the Republic of Belarus. 2015.

- ^ "Belarus: Window of Opportunity (see Table 15, page 66)" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Bell, Imogen (2002). Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2003. Taylor & Francis. p. 132. ISBN 1-85743-137-5.

- ^ Zaprudnik 1993, p. xix

- ^ a b Fedor, Helen (1995). "Belarus – Climate". Belarus: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (26 April 2005). "Belarus cursed by Chernobyl". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 April 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- ^ "The United Nations and Chernobyl – The Republic of Belarus". United Nations. 2004. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Smith, Marilyn. "Ecological reservation in Belarus fosters new approaches to soil remediation". International Atomic Energy Agency. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ^ Larissa Titarenko (2011). "Country Report: Belarus Borders: Borders and policy in Belarus". University of Eastern Finland. p. 14. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Larissa Titarenko. "Country Report: Belarus Borders". University of Eastern Finland. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Profile: Alexander Lukashenko". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 9 January 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Jeffries, Ian (2004). The countries of the former Soviet Union at the turn of the twenty-first century: the Baltic and European states in transition. Routledge. p. 274. ISBN 0-415-25230-X.

- ^ Constitution of Belarus Chapter 4, Art. 90 and 91

- ^ "Belarus 1994 (rev. 2004)". Constitute. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b c "Section IV:The President, Parliament, Government, the Courts". Constitution of Belarus. Press Service of the President of the Republic of Belarus. 2004. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Deputy Prime Ministers of the Republic of Belarus". Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus. 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ Wolfram Nordsieck (2012). "Belarus". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Soviet Local Government". Russia Today Society. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ Rausing, Sigrid (7 October 2012). "Belarus: inside Europe's last dictatorship". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Belarus's Lukashenko: 'Better a dictator than gay'". Reuters. Berlin. 4 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

...German Foreign Minister's branding him 'Europe's last dictator'

- ^ Liabedzka, Anatoly (2008). "Europe's Last Dictatorship". European View. 7 (1): 81–89. doi:10.1007/s12290-008-0029-7. S2CID 154655219.

- ^ Marples, David R (2005). "Europe's Last Dictatorship: The Roots and Perspectives of Authoritarianism in 'White Russia'". Europe-Asia Studies. 57 (6): 895–908. doi:10.1080/1080/09668130500199509. S2CID 153436132.

- ^ "Belarus suspended from the Council of Europe". Press Service of the Council of Europe. 17 January 1997. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- ^ "Republic of Belarus". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "Belarus – Office of the Directorate General of Programmes". coe.int. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "OSCE Report on the October 2004 parliamentary elections" (PDF). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. December 2004. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ "Belarus in the aftermath of the Presidential election of 19 March 2006" (PDF). Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. 11 April 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Belarus rally marred by arrests". BBC News. 2 March 2006. Archived from the original on 13 March 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2006.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (25 December 2010). "Police guard threatened to rape Belarus Free Theatre director after election protest". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Belarus opposition leader Andrei Sannikov jailed, BBC News Online (14 May 2011)

- ^ "Belarus: 7 presidential candidates face 15 years". Kyiv Post. 22 December 2010. Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ Motlagh, Jason (7 July 2011). "Why Belarus' Dictator Is Not Fond of Applause". Time. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ^ "UNITED NATIONS MEMBER STATES | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". www.un.org.

- ^ a b United States Government (2007). "Background Note: Belarus". United States State Department. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/russia-belarus-relations-future-union-state-65288/

- ^ Radio Free Europe (2006). "CIS: Foreign Ministers, Heads Of State Gather In Minsk For Summit". Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ "EU imposes Belarus travel ban". BBC News. BBC. 19 November 2002. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Foreign Policy". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. 2007. Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "Belarus president visits Vatican". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Mackinnon, Robbie Gramer, Amy. "The U.S. Was Set to Send an Ambassador to Belarus. Then Came the Crackdown".

- ^ "Modest Advances in US-Belarus Relations". Jamestown.

- ^ "Belarus Democracy Act Will Help Cause of Freedom, Bush Says". USINO. United States State Department. 22 October 2007. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ "China's Xi promises Belarus $1 billion in loans". Guardian. London. 7 May 2008. Retrieved 4 March 2016.