Around the World in Seventy-Two Days

"Round the World with Nellie Bly" board game box | |

| Author | Nellie Bly |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Pictorial Weeklies |

Publication date | 1890 |

| OCLC | 4363117 |

| Text | Around the World in Seventy-Two Days at Wikisource |

Around the World in Seventy-Two Days is an 1890 book by journalist Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, writing under her pseudonym, Nellie Bly. The chronicle details her 72-day trip around the world, which was inspired by the 1873 book Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne. She carried out the journey for Joseph Pulitzer's tabloid newspaper, the New York World.

Journey

In 1888, Bly suggested to her editor at the New York World that she take a trip around the world, attempting to turn the fictional Around the World in Eighty Days into fact for the first time. A year later, at 9:40 a.m. on November 14, 1889, she boarded the Augusta Victoria, a steamer of the Hamburg America Line,[1] and began her 40,071-kilometre (24,899 mi) journey with the goal of finishing in 75 days.

She brought with her the dress she was wearing, a sturdy overcoat, several changes of underwear and a small travel bag carrying her toiletry essentials. She carried most of her money (£200 in English bank notes and gold in total as well as some American currency)[2] in a bag tied around her neck.[3]

The New York newspaper Cosmopolitan sponsored its own reporter, Elizabeth Bisland, to beat the time of both Phileas Fogg and Bly. Bisland would travel the opposite way around the world.[4][5] Bly, however, did not learn of Bisland’s journey until reaching Hong Kong. She dismissed the cheap competition. "I would not race," she said. "If someone else wants to do the trip in less time, that is their concern."[6]

To sustain interest in the story, the World organized a "Bly Guessing Match" in which readers were asked to estimate Bly's arrival time to the second, with the Grand Prize consisting at first of a free trip to Europe and, later on, spending money for the trip.[3][7]

On her travels around the world, Bly went through England; France, where she met Jules Verne in Amiens; Brindisi in southern Italy; the Suez Canal; Colombo in Ceylon; the Straits Settlements (British territories) of Penang and Singapore on the Malay Peninsula; Hong Kong; and Japan. The development of efficient submarine cable networks and the electric telegraph allowed Bly to send short progress reports,[8] though longer dispatches had to travel by regular post and were thus often delayed by several weeks.[7]

Bly travelled using steamships and the existing railroad systems,[9] which caused occasional setbacks, particularly on the Asian leg of her race.[10] During these stops, she visited a leper colony in China[11][12] and she bought a monkey in Singapore.[11][13]

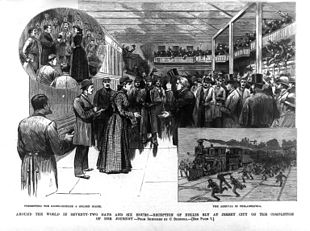

Homecoming

As a result of rough weather on her Pacific crossing, she arrived in San Francisco on the White Star liner Oceanic on January 21, two days behind schedule.[10][14] However, World owner Pulitzer chartered a private train to bring her home, and she arrived back in New Jersey on January 25, 1890, at 3:51 p.m.[8]

Bly arrived back in New York seventy-two days and six hours and 11 minutes after leaving Hoboken. At the time, Bisland was still going around the world. Like Bly, she had missed a connection and had to board a slow, old ship (the Bothina) in the place of a fast ship (Etruria).[15] Bly's journey, at the time, was a world record, though it was bettered a few months later by George Francis Train, who completed the journey in 67 days.[16] By 1913, Andre Jaeger-Schmidt, Henry Frederick and John Henry Mears had improved on the record, the latter completing the journey in less than 36 days.[17]

In popular culture

- In season five, episode seven, of Boardwalk Empire (set in 1931), the character Gillian Darmody reads aloud from this book, the only one she owns.

See also

- A Boy Scout Around the World, a 1928 book based on a similar idea.

References

- ^ Kroeger, Brooke. Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 146

- ^ Kroeger, Brooke. Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 141

- ^ a b Ruddick, Nicholas. "Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age." Canadian Review of American Studies, Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 5

- ^ Barcousky, Len. "Eyewitness 1890: Pittsburgh welcomes home globe-trotting Nellie Bly", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 23, 2009, accessed January 30, 2011

- ^ "Society Topics of the Week.", The New York Times, November 24, 1889, accessed January 30, 2011

- ^ "Nellie on the Fly". The Attic. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b Kroeger, Brooke. Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 150

- ^ a b Ruddick, Nicholas. "Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age." Canadian Review of American Studies, Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 8

- ^ Ruddick, Nicholas. "Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age." Canadian Review of American Studies, Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 6

- ^ a b Bear, David. "Around the World With Nellie Bly." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, November 26, 2006

- ^ a b Ruddick, Nicholas. "Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age." Canadian Review of American Studies, Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 7

- ^ Kroeger, Brooke. Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 160

- ^ Kroeger, Brooke. Nellie Bly – Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist. Times Books Random House, 1994, p. 158

- ^ *Daily Alta California, "Phineas Fogg Outdone", January 22, 1890

- ^ Ruddick, Nicholas. "Nellie Bly, Jules Verne, and the World on the Threshold of the American Age." Canadian Review of American Studies, Volume 29, Number 1, 1999, p. 4

- ^ "William Lightfoot Visscher, Journal profile, part one". www.skagitriverjournal.com. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ New York Times, "A Run Around the World", August 8, 1913

- Marshall Goldberg, "The New Colossus," Diversion Books, 2014

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Around the World in Seventy-Two Days. |

- Nellie Bly's Book: Around the World in Seventy-Two Days, by Nellie Bly. London: Bretano's; New York: Pictorial Weeklies, 1890 at A Celebration of Women Writers

- Around the World in Seventy-Two Days at Project Gutenberg (Audio Book)

Around the World in Seventy-Two Days public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Around the World in Seventy-Two Days public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Information

Article Around the World in Seventy-Two Days in English Wikipedia took following places in local popularity ranking:

- 6 place in 2022-02-23

About the page

Presented content of the Wikipedia article was extracted in 2022-03-02 based on https://en.wikipedia.org/?curid=13398908