2021 Peruvian general election

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 70.05% (first round)[1] 74.57% (second round)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Congressional election | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 130 seats in the Congress of Peru 66 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results of the Congressional election. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

| Constitution |

|

|

General elections were held in Peru on 11 April 2021. The presidential election will determine the President and the Vice Presidents, depending on the results of a run-off between the two top finishers on 6 June 2021. The congressional elections determined the composition of the Congress of Peru. All 130 seats of the unicameral Congress were contested.

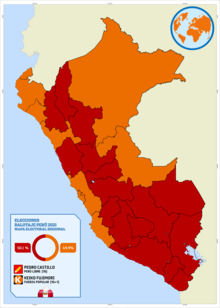

Eighteen candidates participated in the presidential election, the highest number of candidates since the 2006 Peruvian general election.[3] Pedro Castillo, a member of the left-wing Free Peru party, received the most votes in the first round. He faced Keiko Fujimori, the leader of the right-wing Popular Force who had previously narrowly lost the run-offs of the 2011 and the 2016 elections. The official count of the second round indicated that Castillo won 50.12% of valid votes, a lead of 44,058 over Fujimori, but an official outcome is yet to be declared by the National Office of Electoral Processes (ONPE).[4][5]

Electoral system

Presidential election

The President is elected using the two-round system.[6] The first round voting was held on April 11 and allows eligible voters to vote for any viable presidential candidate.[6] The top two candidates who receive a plurality of the vote proceed to the run-off election, which took place on 6 June.[6] The winner of the run-off election and the presidential election is the candidate who receives a plurality of the popular vote.[6][7] However, if in the first round the candidate who is in the first place already gets more than 50% of the popular vote, that candidate will automatically win the election and a run-off election will no longer be needed.[7]

Congressional elections

The 130 members of Congress are elected in 27 multi-member constituencies using open list proportional representation.[8] To enter Congress, parties must either cross the 5% electoral threshold at the national level, or win at least seven seats in one constituency. Seats are allocated using the D'Hondt method.[9][10]

Andean parliament

Peru has 5 places in the Andean Parliament and are elected using a common constituency by open-list.[11]

Date

Early election proposal

President Martín Vizcarra initially presented legislation that would set the conditions for a snap election in 2020. If successful, Vizcarra would not be eligible for re-election.[12][13] The 2020 proposed Peruvian general election would be held on 11 April 2020, to elect a new President of the Republic of Peru, along with 130 congressmen of the Congress of Peru.[14] It was eventually decided to be held on 26 January 2020.[14] Opposition lawmakers condemned Vizcarra's proposal, defending the practice of five year terms.[15] This constitutional reform was rejected.[14]

Official election date

The 2021 Peruvian general election were held on 11 April 2021, to elect the president of the Republic of Peru, two vice presidents of the same party, 130 congressmen of the Congress of Peru and 5 Andean parliamentarians for a five-year term from 2021 to 2026.[16]

On April 11, 130 congressmen were elected in 27 electoral districts, corresponding to the 24 departments, the Province of Lima, the Constitutional Province of Callao and residents living abroad.[16][7]

The elected congressmen will be sworn in and assume office no later than 27 July 2021; the constitutional president of the Republic and his elected vice presidents will do so on 28 July 2021.[17]

Presidential nominations

Main presidential nominees

- George Forsyth is a former football player who played as goalkeeper throughout his sports career. The son of diplomat Harold Forsyth, he entered politics as councilman of La Victoria District in 2010, and as the district's mayor from 2019 until his resignation in October 2020 in order to run for the presidency.[18][19] Previously not-affiliated to party politics, he reached an agreement with National Restoration for his presidential run. Upon his registration, the party filed a name-change in order to be reorganized into National Victory for the general election.[20]

- Pedro Castillo is Free Peru's nominee and schoolteacher from Cajamarca.[21] He is a former Ronda Campesina that defended rural areas from the Shining Path in the 1980s,[22][23] and a politician with the centre-left party Possible Peru from 2002–17.[24] He gained attention in 2017, as he led multiple teacher strikes in five regions against Pedro Pablo Kuczynski's administration.[25] Castillo has called for the renegotiation of government contracts with large businesses and to rewrite the constitution to protect Peruvians from foreign control.[22]

- Keiko Fujimori is the leader of the conservative and far-right[26][27][28] Popular Force. The daughter of former president Alberto Fujimori, she still remains a polarizing figure in Peruvian politics since her last presidential run in 2016, but with lower support due to her parliamentary caucus's obstructionist role during the presidencies of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and Martín Vizcarra.[29] She continues to be viewed unfavorably by a number of people who oppose Fujimori for human rights abuses and corrupt practices, mostly from the left-wing spectrum, and who fear that her victory would mark a return of Fujimorismo. In addition, she has been involved in the Odebrecht scandal, for which she has served in pretrial detention since 2018 with conditional release in 2020.[30] Among her first campaign appearances, she has vowed to pardon her father if winning the presidency in her third run.[31]

- Yonhy Lescano is Popular Action's (AP) nominee. Serving in the Peruvian Congress from 2001 to 2019 representing the constituency of Puno then, Lima, he attained the nomination under a left-wing platform in a competitive primary against the more conservative Alfredo Barnechea.[32] His support is based in the highlands, more punctually in Puno and surrounding rural areas.[33]

- Verónika Mendoza is Together for Peru's (JPP) nominee and leader of the democratic socialist New Peru movement.[34] Since she could not register her own party on time for the election, she sealed a political accord with JPP for her presidential run. Her left-wing platform has remained controversial since her first presidential stint in 2016, in which she placed third and was key in Pedro Pablo Kuczynski's run-off victory by endorsing him in order to prevent Keiko Fujimori to win.[35] She previously served in the Peruvian Congress from 2011 to 2016, representing the constituency of Cuzco.[36]

- Rafael López Aliaga is the leader of Popular Renewal.[37] A businessman with no relevant political experience, he gained political traction due to his ultraconservative rhetoric, adding to his self-proclamation as "the Peruvian Bolsonaro" due to his religious views and far-right policies similar to the Brazilian president.[38][39][40] His campaign runs under a fully right wing platform opposed to abortion and same-sex marriage.[41][42] His collaboration with Fujimorists and the Popular Force party of Keiko Fujimori has also been documented.[43]

- Hernando de Soto is Go on Country's nominee.[44] A free-market economist specialized in informal economy and on the importance of business and property rights, he was a main advisor for President Alberto Fujimori, assisting him with establishing macroeconomic stability for Peru in the aftermath of the Lost Decade.[45] In addition, he has served as an economic advisor to world-leaders since the foundation of the Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), an economic development think-tank based in Lima. In the public sector, he briefly served as a member of the board of directors of the Central Reserve Bank of Peru, in 1979. In previous elections, he supported Keiko Fujimori's candidacies, serving as one of her advisors.[46][47] His party has been described as a mere electoral vehicle by analysts due to his technical profile.[48]

- Julio Guzmán is the founder and leader of the Purple Party. A former public administrator, he first ran for the presidency in 2016 for All for Peru, but was disqualified due to irregularities in the nomination process.[49][50] His party is currently in government with Francisco Sagasti as President of Peru following the removal of Martín Vizcarra and resignation of Manuel Merino, which has affected negatively his campaign due to the government's management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru.[51][52] In addition, a scandal involving him escaping from a fire in an apartment during a lunch with a supposed lover revealed in early 2020 further damaged his public persona.[53]

- Daniel Urresti is a former army general who first attained popularity as Interior Minister in the presidency of Ollanta Humala. Elected to the Peruvian Congress with the highest-vote count in 2020 with Podemos Perú, he attained the party's presidential nomination as the only candidate.[54][55] He previously ran for the presidency for Peruvian Nationalist Party in 2016, although the party withdrew his ticket from the race, and placed second for mayor of Lima at the 2018 municipal election with Podemos Perú.[56] He is currently under investigation for the murder of a journalist during his years in the Peruvian Army, which has proved negative to his campaign, in addition to his wry media exposure from years prior to Congress.[57][58]

- Ollanta Humala is the leader of the Peruvian Nationalist Party and the only former President of Peru running for a second non-consecutive term. A former army lieutenant colonel, he remained unpopular throughout his presidency due to the few advances his government made, in addition to serving a short pre-trial detention from 2017 to 2018 for allegedly receiving bribes from Odebrecht, for which he continues to be under investigation alongside his wife, Nadine Heredia.[59][60]

- Daniel Salaverry is We Are Peru's nominee. An architect from La Libertad, he started a career in politics for mayor of Trujillo with the Peruvian Aprista Party in 2010, and Popular Force in 2014. With the latter, he was elected to the Peruvian Congress in 2016.[61] As a member of the majority caucus, he was elected President of Congress in 2018, but quit the caucus as he supposedly received pressure from the Fujimorist leadership to undermine Martín Vizcarra's presidency.[62] As part of his campaign, Vizcarra remains his main political asset for his presidential run due to the former president's congressional candidacy for the constituency of Lima.[63]

- César Acuña is the founder and leader of Alliance for Progress. An entrepreneur in the field of education, he entered politics in 2000 when elected to the Peruvian Congress, in which he served until 2006. Subsequently, he served as mayor of Trujillo from 2007 to 2014, and as governor of La Libertad in 2015. He initially ran for the presidency in the 2016, but was disqualified for alleged vote buying in a campaign trail.[64] In addition, his popularity has diminished due to his party's recent voting records in Congress, thus contradicting his campaign rhetoric, although at first leading the congressional polling after impressively attaining the second largest number of seats at the 2020 parliamentary election.[65]

Minor presidential nominees

- Alberto Beingolea is the leader of the centre-right Christian People's Party.[66] He previously served in the Peruvian Congress from 2011 to 2016.[67] Prior to entering politics, he had a successful career as a sports journalist. Most recently, he ran for mayor of Lima in the 2018 municipal election, in which he placed fourth.[68]

- Marco Arana is the leader of the Broad Front, a left-wing informal coalition of parties and unions.[69] A former bishop from Cajamarca, he ran unsuccessfully for the vice presidency in 2016 with Verónika Mendoza as the party's presidential nominee.[70] He served in the Peruvian Congress from 2016 to 2019.

- Rafael Santos is Peru Secure Homeland's nominee.[71] A businessman in the agrarian exportation area, he entered politics when he successfully ran for mayor of Pueblo Libre in 2006. He was reelected in 2010, but failed to attain a third term in 2014. He was previously a member of the Christian People's Party.[72]

- José Vega is the leader of Union for Peru.[73] A congressman for the constituency of Lima, he further radicalized his party following his accord with the imprisoned military revolt leader, Antauro Humala, the brother of former president Ollanta Humala.[74] He previously served a full term in the Peruvian Congress from 2006 to 2011.

- Ciro Gálvez is the leader of the National United Renaissance.[75] A lawyer and notary based in Junín, his platform remains conservative, declaring to be in opposition to LGBT rights. For the election, his ticket includes former pastor and businessman Claudio Zolla as his first running-mate, due to a political accord with the New Peru Liberal Party, a libertarian movement led by Zolla.[76]

- Andrés Alcántara is the leader of Direct Democracy.[77] A left-wing populist, he presides the FONAVI housing pensioners association, for which he campaigned strongly since early 2000s until 2010 for the government's full pension devolution, which was achieved following via referendum. His campaign platform is poised in reforming and eventually replacing the Constitution of Peru.[78] He ran for the vice presidency in the last three general elections.[79]

Withdrawn nominees

| Party | Ticket | Withdrawal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | for President | for First Vice President | for Second Vice President | Date | Motive |

| Peruvian Aprista Party Partido Aprista Peruano |

Nidia Vílchez Yucra | Iván Hidalgo Romero | Olga Cribilleros Shigihara | 16 January 2021 | Prompted upon the National Jury of Elections' rejection of inscription of parliamentary lists past the deadline.[80] |

Rejected nominees

| Party | Ticket | Rejection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | for President | for First Vice President | for Second Vice President | Date | Motive |

| Contigo Political Party Partido Político Contigo |

Pedro Angulo Arana | Casimira Mujica | Alexander von Ehren | 22 December 2020 | Did not meet the deadline to register for the election on time.[81] |

| Peru Nation Perú Nación |

Francisco Diez Canseco | Nancy Cáceres | Manuel Salazar | 22 December 2020 | Did not meet the deadline to register for the election on time.[82] |

| Front of Hope 2021 Frente de la Esperanza 2021 |

Fernando Olivera | Elizabeth León | Carlos Cuaresma | 24 December 2020 | Party did not fulfill requirements for registration in order to participate.[83] |

| All for Peru Todos por el Perú |

Fernando Cillóniz | Blanca Wong | Jaime Freundt | 26 December 2020 | Party lacked the legitimacy to participate in the election due to unsolved internal legal disputes.[84] |

Disqualified nominees

| Party | Ticket | Rejection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | for President | for First Vice President | for Second Vice President | Date | Motive |

| Union for Peru Unión por el Perú |

José Vega | Haydee Andrade | Daniel Barragán | 29 December 2020 | Incomplete information regarding income on the nominees registration form.[85] The decision was ultimately revoked by the National Jury of Elections, thus admitting and registering the ticket on 6 February 2021.[86] |

| Alliance for Progress Alianza para el Progreso |

César Acuña | Carmen Omonte | Luis Iberico Núñez | 8 January 2021 | Incomplete information regarding the presidential nominee's income in registration form.[87] Disqualification revoked by the National Jury of Elections on 22 January 2021, following an appeal.[88][89] |

| We Can Peru Podemos Peru |

Daniel Urresti | Maria Teresa Cabrera | Wilbert Portugal | 4 February 2021 | Unanswered questions about the internal democracy of the party.[90] Disqualifiation revoked by the National Jury of Elections on 18 February 2021, following an appeal.[91] |

| National Victory Victoria Nacional |

George Forsyth | Patricia Arévalo | Jorge Chávez Álvarez | 10 February 2021 | Incomplete information regarding income on the nominees registration form.[92] Disqualification revoked by the National Jury of Elections on 5 March 2021, following an appeal.[93] |

| Popular Renewal Renovación Popular |

Rafael López Aliaga | Neldy Mendoza | Jorge Montoya | 25 February 2021 | Nominee's public statement on donating his salary to charity if elected president is presumed as alleged vote buying.[94] Disqualification revoked by the National Jury of Elections on 5 March 2021, following an appeal.[88] |

| National United Renaissance Renacimiento Unido Nacional |

Ciro Gálvez | Sonia García | Claudio Zolla | 25 February 2021 | Incomplete information regarding the presidential nominee's income in registration form.[95] Disqualification revoked by the National Jury of Elections on 5 March 2021, following an appeal.[88] |

Campaign

Campaign issues

Constitution of 1993

Multiple candidates called for constitutional reform or an entirely new constitution in order to reduce corruption and to bring more prosperity to Peru. Constitutional changes in Peru are overseen by the Congress of Peru.[96] In order to hold a constitutional referendum, a majority vote from congress is required to approve the election.[96][97] All proposed constitutional reforms would also have to be approved by congress.[96] Following the first round elections and the divided legislators from numerous different parties voted into congress, chances of candidates changing the constitution were limited.[96][97]

Corruption in Peru has been pervasive and was recently brought to attention during the Odebrecht scandal, which involved Odebrecht paying politicians to receive contracts for public works projects.[98] BBC News wrote in 2019 that "Peru is perhaps where [Odebrecht] has caused the most severe crisis" and that "[t]he scandal has discredited virtually the entire political elite of the country, as all major parties and players have been implicated."[98] The Odebrecht scandal led to several incidents in Peruvian politics; the suicide of former president Alan García,[98] the order for the arrest of former president Alejandro Toledo[99] as well as the first impeachment process against Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and later his resignation from the presidency.[100] Two candidates in the 2021 elections, Keiko Fujimori and Julio Guzmán, were also under investigation regarding alleged bribes from Odebrecht during their earlier electoral campaigns.[101][102] Kuczynski's successor Martín Vizcarra reacted to the Odebrecht scandal with multiple anti-corruption initiatives,[103] although Vizcarra was controversially removed from office for his own alleged involvement in corruption and was replaced with President of Congress Manuel Merino.[104] Vizcarra's removal was very unfavorable with Peruvians and resulted with the 2020 Peruvian protests.[105] Merino would be president for only five days and would later be replaced by Francisco Sagasti following a vote from congress.[106]

Pedro Castillo proposed to elect a constituent assembly to replace the constitution inherited from Alberto Fujimori's regime, with Castillo saying "it serves to defend corruption at macro scale" and that he would respect the rule of law by calling for a constitutional referendum to determine whether a constituent assembly should be formed or not.[107][108][109][110][111] Veronika Mendoza also embraced calls for a new constitution instead of amendments, stating "Our current national institutional framework, enshrined in the Constitution, establishes that education, health care, and housing are for-profit enterprises, and that life itself is a commodity to be bought and sold. What this means is that political power is concentrated in the hands of those with money, and not with the Peruvian people."[112]

George Forsyth, the initial frontrunner in the campaign, benefitted from his celebrity fame and not being involved with the traditional political parties being investigated for corruption.[101] Forsyth called for constitutional amendments instead of a new constitution, supporting an amendment that would declare corruption a crime against humanity.[113]

One of the few candidates to support the existing constitution was Keiko Fujimori. Fujimori has stated that she would keep the 1993 constitution of her father Alberto Fujimori in place, instead advocating for the use of a "heavy hand" if elected president, stating: "Democracy cannot be weak. It must be supported by a solid principle of authority."[102][114]

COVID-19 pandemic

Peru is one of the worst-affected nations in the world from the COVID-19 pandemic, with at least 0.5% of the population dying during the pandemic.[115][116][117] The crisis became so intense by January 2021 due to a second wave of infections that ICU bed occupancy in Peru rose to 90%, with medical workers beginning to participate in strikes due to their harsh work conditions.[118]

Forsyth criticized the COVID-19 lockdowns of the Peruvian government, saying that they caused economic distress and that the National Emergency Operations Center (COEN) should be activated for a civil-military partnership to combat further infection.[119] Mendoza was also critical of how lockdowns were initiated, saying that the government should provide support for families affected by lockdowns, promoted a partnership with Argentina to acquire the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and denounced the potential commercialization of the COVID-19 vaccine in Peru.[120][121]

On 24 February 2021, following an approach to advise Francisco Sagasti on the COVID-19 pandemic management in Peru, Hernando de Soto announced the first shadow cabinet in Peruvian history. Mainly composed of his campaign technical team, the main purpose of the opposition cabinet is to offer an alternative in order for the government to concur and apply De Soto's proposals during the crisis.[122][123]

Economy

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, Peru's gross domestic product fell 30.2 percent in the second quarter of 2020, the largest decline of all major economies, with many small service businesses that represent the majority of businesses of Peru's economy going bankrupt during the crisis.[124] Medical experts commented that the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak in Peru can be explained at least in part due to existing socioeconomic circumstances; nearly one-third of Peruvians lived in overcrowded homes, 72% had informal jobs requiring daily work and many needed to travel daily to markets to purchase food since only 49% of households own refrigerators or freezers; even in urban areas it is only 61%.[125]

Political scientist Paula Muñoz of the Universidad del Pacífico described Forsyth as "a pro-business guy", while Americas Quarterly wrote "his views on big economic issues are less clear."[126] Forsyth and Fujimori both shared his support for the privatization of public utilities and the deregulation of the economy, with the two saying that government intervention hinders growth.[127][128] Fujimori also stated that she wanted to make "the State the main partner of entrepreneurs."[114] In contrast, Mendoza criticized the neoliberal policies instituted in Peru since the 1990s, demanded "the decommodification of goods like health, education, and housing", and promoted the government funding of sustainable agricultural and energy projects, all while protecting the environment.[112]

Immigration

As a result of the Venezuelan refugee crisis, Peru was home to over one million Venezuelans in February 2021.[129][130] At that time, the Peruvian Armed Forces were deployed in a joint operation with Ecuadorian counterparts to the Ecuador-Peru border to prevent the entry of illegal migrants, with the armed forces stating that it was to prevent further introduction of COVID-19 in Peru.[130] Human rights organizations criticized the militarization of the border, saying that they are not properly trained for border enforcement and that it violates the human rights of migrants.[130] Xenophobia towards Venezuelans in Peru has also increased, as some politicians have blamed increased crime on the migrants, although the Brookings Institution and Migration Policy Institute found that Venezuelan participate in less crime in Peru than native Peruvians.[131]

On the immigration topic, Forsyth's responses varied; he stated that "Peru is a generous country that opens its doors to foreigners"[127] while he also supported deploying more authorities to control the border, stating that migrants "have humiliated our National Police" and "We need the principle of authority in the country. [...] We need an empowered police to defend all of us Peruvians."[132] Regarding her position on immigration, Mendoza stated: "Migration must be considered on humanitarian criteria. Peruvians have also migrated." Although some controls should be instituted to prevent criminals from entering, she promoted migrants as "people who can contribute to the country."[133] Fujimori supported increased border security, promoting the utilization of police and the Peruvian Armed Forces for guarding the border.[114]

Analysis

Party politics

Political parties in Peru have been controlled by individuals seeking their own benefits, usually financial compensation.[134] According to The Economist, political graft was the largest challenge facing Peru instead of the ideological battles in the press.[134] Due to the large divisions of parties in congress, with over eleven parties elected into the Congress of Peru, whoever was elected into the presidency was expected to be weak due to the fractured congress.[134] Political analyst Giovanna Peñaflor agreed with the theory of a weak presidency, saying that the fragmented congress would leave the executive vulnerable to legislators.[135]

When discussing the state of party politics during the election, especially among congress, political scientist Adriana Urrutia said: "Political parties are no longer a vehicle for representation of the citizenry."[136] Urrutia explained that traditional parties are known among Peruvians to represent groups related to corruption in the country, including lucrative private universities, illegal logging and mining, among others.[136]

Regarding the first round of presidential elections, Javier Puente, assistant professor of Latin American Studies at Smith College in the North American Congress on Latin America wrote: "With a baffling number of candidates – 18 in total – the 2021 presidential ballot included convicted felons, presumed money launderers, xenophobes, a fascist billionaire, an overrated and outdated economist, a retired mediocre footballer, a person accused of murdering a journalist, and other colorful figures. The vast majority of candidates represented the continuation of the neoliberal economic model that has been responsible for decades of meager financial performance and unequal growth."[137] Puente stated that only three leftist candidates proposed alternatives to the neoliberal politicians; Veronika Mendoza, Marco Arana and Pedro Castillo, describing Castillo as "far from being a 'comrade' who will champion leftist demands, Castillo is the new face of an anti-system impulse. [...] Only in a neoliberal system that outcasts any form of market dissent as radical would a figure like Castillo acquire a role as a leftist."[137]

Ideologies

Due to the internal conflict in Peru involving far-left guerrilla groups attacking Peru's institutions which mainly occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, sentiments towards left-wing political parties have a negative stigma skewed against them.[138][139] While campaigning occurred during the elections, right-wing politicians would often baselessly characterize left-wing politicians as terrorists, or terrucos in Peruvian Spanish, with the attacks being so common that they were given the term terruqueo.[139] The Americas Quarterly argues that such behavior may result in less support for the leftist candidate Verónika Mendoza and promote political polarization within Peru.[139] With the ongoing political crisis that saw in the span of two years the dissolution of the Congress of Peru and the removal of three presidents (Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, Martín Vizcarra, and Manuel Merino), concerns were raised among analysts about the increased political polarization's relationship with Peru's democratic stability.[136] Lead researcher of pollster Institute of Peruvian Studies, Patricia Zárate, stated: "I think the scenario that's coming is really frightening."[136]

Some scholars have recognized the similarities of Fujimori and Castillo; both are cultural conservatives opposing same-sex marriage and abortion, as campaigning for the second round of elections began.[140] Olga González, associate dean of the Kofi Annan Institute for Global Citizenship at Macalester College, stated that the situation is more complex than "binaries" between social classes, although she acknowledged that such dichotomies "speak to how polarized the country is."[140]

Vargas Llosa analysis

Regarding the second round of presidential elections, Peruvian Nobel Prize laureate and writer Mario Vargas Llosa said that the candidate Castillo would undermine democracy, ruin Peru’s economy and leave the country "with all the characteristics of a communist society" and that "Peruvians should vote for Keiko Fujimori because she represents the lesser of two evils and, if she's in power, there are more possibilities of saving our democracy." Vargas Llosa urged Fujimori to respect freedom of expression, presidential term limits, and rule out a pardon for Vladimiro Montesinos, who served as Alberto Fujimori's head of intelligence service.[141]

Political scientist professor Farid Kahhat of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru stated that "Vargas Llosa has a habit of issuing categorical judgments that later make him look ridiculous. ... Frankly, any Peruvian who has followed Vargas Llosa’s career realizes that he is not worth taking seriously."[142] Vargas Llosa ran and lost against Alberto Fujimori in Peru's 1990 elections,[141] and had previously criticized Fujimori, making statements such as "the worst option is that of Keiko Fujimori because it means the legitimation of one of the worst dictatorships that Peru has had in its history"[143] and that "Keiko is the daughter of a murderer and a thief who is imprisoned, tried by civil courts with international observers, sentenced to 25 years in prison for murder and theft. I do not want her to win the elections."[144] Argentine newspaper Página/12 criticized Vargas Llosa, noting his reversal on previous statements, stating that "the neoliberal right is allied with authoritarian Fujimori", and arguing that Vargas Llosa was "betting on fear and resuscitating an anti-communist coalition."[145]

Rural vs. urban debate

In democratic elections since 1919, eleven of eighteen presidents of Peru were from Lima, even as many Peruvians in rural areas were not able to vote until 1979 when the constitution allowed illiterate individuals to vote.[146] Alhough economic statistics show improved economic data in Peru in recent decades, the wealth earned between 1990 and 2020 was not distributed throughout the country; living standards showed disparities between the more-developed capital city of Lima and similar coastal regions while rural provinces remained impoverished.[23][142][146] The COVID-19 pandemic exasperated these disparities even further.[142][146] Kahhat stated that "market reforms in Peru have yielded positive results in terms of reducing poverty ... But what the pandemic has laid bare, particularly in Peru, is that poverty was reduced while leaving the miserable state of public services unaltered – most clearly in the case of health services."[142]

Leading to the election, opinion polls showed wealthy Peruvians favored Keiko while the poor supported Castillo, with the latter demographic representing a larger portion of voters.[147] Castillo's candidacy brought attention to this divide with much of his support being earned in the exterior portions of the country.[146] In May 2021, Americas Quarterly wrote: "Life expectancy in Huancavelica, for example, the region where Castillo received his highest share of the vote in the first round, is seven years shorter than in Lima. In Puno, where Castillo received over 47% of the vote, the infant mortality rate is almost three times that of Lima's."[146]

According to historian José Ragas of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, although Castillo was accused of being linked to communist terrorism, "in places where terrorism caused the most bloodshed, Castillo won by a lot."[146] The separation of Lima and rural Peru also led to the underestimation of Castillo's performance in first-round elections.[146] Castillo received a majority vote in all but one of Peru's mining provinces, with researcher Hugo Ñopo of the Lima-based GRADE stating: "The regions that provide those minerals that make Peru rich do not improve the living standards of the local communities, ... Many people perceive that the winners of these three decades are not them, but are the people in Lima and the big cities."[146] Sociologist Maritza Paredes of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru shared similar thoughts, saying: "People see that all the natural resources are in the countryside but all the benefits are concentrated in Lima."[23] In contrast, Fujimori received support from Lima's elite according to Kahhat.[142] Kahhat said that evangelical Christians, businesses, media organizations, and the armed forces supported Fujimori, with the nation's largest media organization El Comercio group openly advocating for her election.[142]

Opinion polls

Controversy

Media

During the intense periods of internal conflict in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s, the government, military, and media in Peru described any individual who was left on the political spectrum as being a threat to the nation, with many students, professors, union members, and peasants being jailed or killed for their political beliefs.[138] Such sentiments continued for decades into the election, with Peru's right-wing elite and media organizations collaborating with Fujimori's campaign by appealing to fear when discussing political opponents.[138] In the second round of elections, Peru's major media networks aligned with Fujimori to discredit Castillo.[142][138] While news organizations polished Fujimori's image and praised her, they assisted her media campaign tactic which included attacks accusing Castillo of being linked to armed communist groups.[23][138][148] She described Castillo as a "car bomb" destined to "explode the last 30 years of development."[23] Billboards were posted in Lima to call on Peruvians "to vote against communism."[148] The Guardian described accusations linking Castillo to Shining Path as "incorrect", while the Associated Press said that allegations by Peruvian media of links to Shining Path were "unsupported."[149][150]

Censorship allegations

Colombian journalist Clara Elvira Ospina of Grupo who was the journalistic director of La República's América Televisión and El Comercio's Canal N was removed from her position on 24 April 2021 after having served in the position for a total of nine years.[151] Grupo La República shareholder Gustavo Mohme Seminario said that the firing occurred shortly after Ospina had a conversation with Keiko Fujimori and other news editors.[151] One anonymous individual said that Ospina allegedly told Fujimori that the journalistic direction of the media organizations would not favor her or Castillo, instead using impartiality during their coverage.[151]

Mohme criticized the dismissal of Ospina, saying: "I do not want to be a silent troupe of these legal shenanigans that seeks to arbitrarily impose who will assume the reins of the main television channel in the country." Mohme resigned from the editorial council.[151][152] The Knight Center for Specialized Journalism wrote that Mohme described the incident as self-censorship.[151] Diego Salazar, former editor of Peru21, said that the dismissal was "an obvious sign that you are seeking to intervene in the electoral campaign in a way that is not journalistic."[151] Members of Cuarto Poder, an investigative journalism program on América TV, had their letter to the board of directors leaked in May 2021 where they said that Ospina's dismissal "represented serious damage to the work we do and to the image of the program", and accused her replacement, Gilberto Hume, of having an agenda against Castillo and in favor of Fujimori, writing "Within that conversation it was implicit that (Hume) asked us to support the candidate of Fuerza Popular to the detriment of the candidate of Free Peru."[151][153] Luis Galarreta, Fujimori's pick for first vice president, said that the meeting with Ospina was discussing debates and "nothing more", adding that "nobody thinks of influencing a medium."[154]

Shortly after polls closed on 6 June, the journalists of Cuarto Poder who sent a letter criticizing alleged censorship were fired by La República's América Televisión and El Comercio's Canal N.[153]

San Miguel del Ene attack

Comrade Vilma, with close ties to Comrade José, head of the Militarized Communist Party of Peru (MPCP), a communist organization that split from Shining Path at least ten years before the San Miguel del Ene attack,[155][138][156] called for a boycott of elections on 14 May.[157] During the second round of elections, Vilma called on voters not to vote for Fujimori, stating that anyone who voted for her would be the "accomplice of genociders and the corrupt."[157]

On 23 May, a mass killing of eighteen people occurred in San Miguel del Ene, a rural area in the Vizcatán del Ene District of Satipo Province.[158] Along with the corpses, some of which were burned, leaflets signed by the MPCP were found, featuring the hammer and sickle and defining the attack as a social cleansing operation.[159][156] The leaflets also called for a boycott of the 6 June elections and accused those who voted for Keiko Fujimori and her Popular Force party of treason.[160][161] The military quickly accused Shining Path of the attack, although they were allegedly referring to the MCPC.[138][156] However, no formal investigation had been performed before the links to Shining Path were claimed.[138][156] OjoPúblico described the media release by the military as "an inaccurate reference to the Shining Path."[156]

The attack and subsequent media coverage would provide increased support for Fujimori, whose rhetoric aligned Castillo with armed communists.[23][148] The Fujimori campaign used the attack as a springboard for support, pointing to alleged ties between MOVADEF, a Shining Path political group, and Castillo, attempting to align him to the attack.[138] Fujimori expressed condemnation against the attack during a press conference in Tarapoto as well as regret that "bloody acts" still happened in the country and her condolences to the relatives of the victims.[162] Pedro Castillo also condemned the killings during a rally in Huánuco, expressing solidarity towards the relatives of the victims and also urging the National Police to investigate the attack to clarify the events.[163] Vladimir Cerrón, Secretary General of Free Peru, stated that "the right-wing needed [Shining] Path to win"; Cerrón deleted the tweet moments later while condemning any act of terrorism.[164] Prime Minister Nuria Esparch, who held the position of the Ministry of Defense, condemned the attack and guaranteed that the electoral process would take place normally.[165]

Claims of fraud

In order to avoid the questions of election legitimacy, election authorities in Peru approved the use of election monitoring.[166] In total, one hundred and fifty observers (ninety-nine in Peru and fifty-one abroad) were approved to observe elections throughout Peru.[166] The origin of the observers were from twenty-two different countries, with thirty-five observers from the Organization of American States, while others were from Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Spain, Switzerland, the United States, and Uruguay.[166] Observer approval required providing election authorities observation plans; these plans included protocols to inform authorities of crimes, violations of electoral law or any complaints they collected.[166] Observers were then responsible with providing an official, final report to authorities.[166] According to OjoPúblico, "the observers carry out the review of the activities of election day, ranging from the installation of the voting tables, the conditioning of the secret chambers, the conformity of the ballots, the minutes, the amphorae and any other electoral material, to the counting, the counting of the vote and the transfer of the electoral records at the end of the day."[166]

After Castillo took the lead during the ballot-counting process, Fujimori disseminated claims of electoral fraud.[167][168] In a media event following election day, Fujimori alleged that a "series of irregularities which worry us", while presenting photographs and videos in support of her allegations, accusing Free Peru of attempting to "distort and delay" the election process.[167][168] According to The Guardian, various international observers countered Fujimori's claims, stating that the election process was conducted in accordance with international standards.[167] Observers from the Inter-American Union of Electoral Organizations, the Organization of American States, and the Progressive International denied any instances of widespread fraud and praised the accuracy of the elections.[169][170] The Guardian also reported that analysts and political observers criticized Fujimori's remarks, noting that it made her appear desperate after losing her third presidential run in a ten year period.[167] Fernando Tuesta, political scientist from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, stated, "It's extremely regrettable that when the result is not favourable, that the candidate talks about fraud. It's terrible, ... They have been talking about fraud because they don’t want to respect the result."[167] On 9 June, Fujimori sought to have around 200,000 votes annulled and for 300,000 votes to be reviewed.[171]

Preliminary results

President

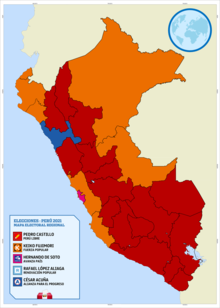

The first round was held on 11 April.[7][172] The first exit polls published indicated that underdog nominee Pedro Castillo of Free Peru had placed first in the first round of voting with approximately 16.1% of the vote, with Hernando de Soto and Keiko Fujimori tying with 11.9% each.[172] Yonhy Lescano, Rafael López Aliaga, Verónika Mendoza, George Forsyth followed, with each receiving 11.0%, 10.5%, 8.8%, and 6.4%, respectively.[172] César Acuña and Daniel Urresti received 5.8% and 5.0%, respectively, while the rest of the nominees attained less than 3% of the popular vote.[173][174]

By department

| Department | Castillo Free Peru |

Fujimori Popular Force |

López Aliaga Popular Renewal |

De Soto Go on Country |

Lescano Popular Action |

Mendoza Together for Peru |

Other candidates |

Valid votes |

Turnout | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Amazonas | 34,411 | 26.1% | 17,805 | 13.5% | 8,269 | 6.3% | 4,433 | 3.4% | 12,698 | 9.6% | 8,887 | 6.7% | 45,557 | 34.5% | 132,060 | 60.1% |

| Ancash | 110,620 | 23.4% | 67,394 | 14.3% | 42,312 | 9.0% | 34,562 | 7.3% | 38,911 | 8.2% | 39,786 | 8.4% | 138,200 | 29.3% | 471,785 | 69.3% |

| Apurimac | 88,812 | 53.4% | 10,879 | 6.5% | 7,768 | 4.7% | 6,531 | 3.9% | 15,649 | 9.4% | 15,368 | 9.2% | 21,179 | 12.7% | 166,186 | 69.4% |

| Arequipa | 256,224 | 32.2% | 40,216 | 5.1% | 71,053 | 8.9% | 148,793 | 18.7% | 88,708 | 11.1% | 55,269 | 6.9% | 135,448 | 17.0% | 795,711 | 78.8% |

| Ayacucho | 130,224 | 52.0% | 17,751 | 7.1% | 11,490 | 4.6% | 8,995 | 3.6% | 20,315 | 8.1% | 24,506 | 9.8% | 37,269 | 14.9% | 250,550 | 68.6% |

| Cajamarca | 232,418 | 44.9% | 54,962 | 10.6% | 31,129 | 6.0% | 25,156 | 4.9% | 38,677 | 7.5% | 29,746 | 5.7% | 105,374 | 20.4% | 517,462 | 62.6% |

| Callao | 33,750 | 6.4% | 79,699 | 15.2% | 78,066 | 14.9% | 78,920 | 15.0% | 34,965 | 6.7% | 38,233 | 7.3% | 181,634 | 34.6% | 525,267 | 75.2% |

| Cusco | 232,178 | 38.2% | 27,132 | 4.5% | 29,618 | 4.9% | 40,423 | 6.6% | 60,659 | 10.0% | 123,397 | 20.3% | 94,626 | 15.6% | 608,033 | 73.5% |

| Huancavelica | 79,895 | 54.2% | 8,449 | 5.7% | 5,060 | 3.4% | 4,591 | 3.1% | 16,727 | 11.3% | 10,091 | 6.8% | 22,574 | 15.3% | 147,387 | 67.6% |

| Huanuco | 110,978 | 37.6% | 32,827 | 11.1% | 33,787 | 11.4% | 15,822 | 5.4% | 22,565 | 7.6% | 15,556 | 5.3% | 63,688 | 21.6% | 295,223 | 68.3% |

| Ica | 56,597 | 14.0% | 62,055 | 15.3% | 46,098 | 11.4% | 39,929 | 9.8% | 39,461 | 9.7% | 30,602 | 7.5% | 130,887 | 32.3% | 405,629 | 76.0% |

| Junin | 131,438 | 22.9% | 80,057 | 13.9% | 52,599 | 9.2% | 54,124 | 9.4% | 66,214 | 11.5% | 52,270 | 9.1% | 137,396 | 23.9% | 574,098 | 71.9% |

| La Libertad | 90,078 | 11.5% | 131,441 | 16.8% | 95,765 | 12.2% | 84,444 | 10.8% | 47,218 | 6.0% | 37,372 | 4.8% | 296,598 | 37.9% | 782,916 | 68.9% |

| Lambayeque | 73,279 | 12.9% | 121,263 | 21.4% | 86,126 | 15.2% | 50,087 | 8.8% | 51,467 | 9.1% | 28,866 | 5.1% | 155,480 | 27.4% | 566,568 | 71.4% |

| Lima | 416,537 | 7.8% | 753,785 | 14.2% | 869,950 | 16.4% | 870,582 | 16.4% | 362,668 | 6.8% | 431,425 | 8.1% | 1,602,623 | 30.2% | 5,307,570 | 74.6% |

| Loreto | 15,432 | 4.9% | 51,900 | 16.6% | 16,378 | 5.3% | 18,816 | 6.0% | 34,773 | 11.2% | 19,502 | 6.3% | 155,025 | 49.7% | 311,826 | 61.0% |

| Madre de Dios | 23,945 | 37.1% | 7,278 | 11.3% | 4,041 | 6.3% | 3,996 | 6.2% | 6,601 | 10.2% | 4,372 | 6.8% | 14,341 | 22.2% | 64,574 | 71.1% |

| Moquegua | 33,665 | 34.4% | 4,617 | 4.7% | 6,832 | 7.0% | 10,183 | 10.4% | 15,412 | 15.7% | 7,190 | 7.3% | 20,027 | 20.5% | 97,926 | 77.2% |

| Pasco | 34,187 | 34.2% | 12,607 | 12.6% | 8,009 | 8.0% | 5,102 | 5.1% | 11,871 | 11.9% | 6,896 | 6.9% | 21,324 | 21.3% | 99,996 | 63.6% |

| Piura | 70,968 | 10.1% | 173,891 | 24.8% | 68,316 | 9.8% | 63,842 | 9.1% | 51,223 | 7.3% | 44,576 | 6.4% | 227,714 | 32.5% | 700,530 | 66.8% |

| Puno | 292,218 | 47.5% | 17,514 | 2.8% | 15,918 | 2.6% | 21,665 | 3.5% | 175,712 | 28.5% | 35,484 | 5.8% | 57,010 | 9.3% | 615,521 | 81.9% |

| San Martin | 67,000 | 21.4% | 46,699 | 14.9% | 26,561 | 8.5% | 21,825 | 7.0% | 31,498 | 10.0% | 17,122 | 5.5% | 102,765 | 32.8% | 313,470 | 69.2% |

| Tacna | 64,521 | 33.2% | 9,363 | 4.8% | 17,842 | 9.2% | 21,000 | 10.8% | 28,696 | 14.8% | 14,068 | 7.2% | 38,779 | 20.0% | 194,269 | 77.8% |

| Tumbes | 7,613 | 7.7% | 36,403 | 37.1% | 8,799 | 9.0% | 7,123 | 7.3% | 7,046 | 7.2% | 5,242 | 5.3% | 26,015 | 26.5% | 98,241 | 74.6% |

| Ucayali | 26,339 | 14.0% | 40,510 | 21.5% | 14,981 | 8.0% | 11,124 | 5.9% | 14,359 | 7.6% | 15,092 | 8.0% | 65,965 | 35.0% | 188,370 | 66.3% |

| Peruvians Abroad | 10,602 | 6.6% | 22,887 | 14.1% | 34,767 | 21.5% | 21,552 | 13.3% | 11,617 | 7.2% | 21,185 | 13.1% | 39,146 | 24.2% | 161,756 | 22.8% |

| Total | 2,723,929 | 18.9% | 1,929,384 | 13.4% | 1,691,534 | 11.8% | 1,673,620 | 11.6% | 1,305,710 | 9.1% | 1,132,103 | 7.9% | 3,936,644 | 27.4% | 14,392,924 | 70.0% |

| Source: ONPE (100% counted) | ||||||||||||||||

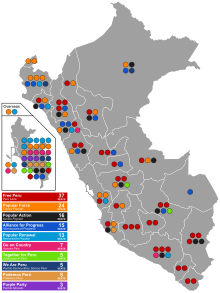

Congress

The Popular Action, the largest party in the previous legislature, lost some of its seats, and previous parliamentary parties like Union for Peru (UPP) and the Broad Front (FA) had their worst results ever while attaining no representation.[16] The Peruvian Nationalist Party of former President Ollanta Humala and National Victory of George Forsyth (who led polling for the presidential election earlier in the year) failed to win seats as well.[16] New or previously minor parties such as Free Peru, Go on Country and Together for Peru and Popular Renewal, the successor of National Solidarity, had good results, with Free Peru becoming the largest party in Congress.[16] Contigo, the successor to former president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski's Peruvians for Change party, failed to win a seat once again and received less than 1% of the vote.[16]

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Peru | 1,724,354 | 13.41 | 37 | +37 | |

| Popular Force | 1,457,694 | 11.34 | 24 | +9 | |

| Popular Renewal | 1,199,705 | 9.33 | 13 | +13 | |

| Popular Action | 1,159,734 | 9.02 | 16 | −9 | |

| Alliance for Progress | 969,726 | 7.54 | 15 | −7 | |

| Go on Country – Social Integration Party | 969,092 | 7.54 | 7 | +7 | |

| Together for Peru | 847,596 | 6.59 | 5 | +5 | |

| We Are Peru | 788,522 | 6.13 | 5 | −6 | |

| Podemos Perú | 750,262 | 5.83 | 5 | −6 | |

| Purple Party | 697,307 | 5.42 | 3 | −6 | |

| National Victory | 638,289 | 4.96 | 0 | New | |

| Agricultural People's Front of Peru | 589,018 | 4.58 | 0 | −15 | |

| Union for Peru | 266,349 | 2.07 | 0 | −13 | |

| Christian People's Party | 212,820 | 1.65 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peruvian Nationalist Party | 195,538 | 1.52 | 0 | New | |

| Broad Front | 135,104 | 1.05 | 0 | −9 | |

| Direct Democracy | 100,033 | 0.78 | 0 | 0 | |

| National United Renaissance | 97,540 | 0.76 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peru Secure Homeland | 54,859 | 0.43 | 0 | 0 | |

| Contigo | 5,787 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 12,859,329 | 100.00 | 130 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 12,859,329 | 72.56 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 4,863,287 | 27.44 | |||

| Total votes | 17,722,616 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 25,287,954 | 70.08 | |||

| Source: ONPE, Ojo Público | |||||

Andean Parliament

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Peru | 1,713,196 | 16.24 | 1 | +1 | |

| Popular Force | 1,249,938 | 11.85 | 1 | –2 | |

| Popular Renewal | 1,094,709 | 10.37 | 1 | +1 | |

| Popular Action | 964,563 | 9.14 | 1 | +1 | |

| Go on Country – Social Integration Party | 919,212 | 8.71 | 1 | +1 | |

| Podemos Perú | 747,303 | 7.08 | 0 | 0 | |

| Together for Peru | 736,001 | 6.97 | 0 | 0 | |

| Alliance for Progress | 713,542 | 6.76 | 0 | 0 | |

| Agricultural People's Front of Peru | 670,393 | 6.35 | 0 | 0 | |

| Purple Party | 582,904 | 5.52 | 0 | 0 | |

| We Are Peru | 447,437 | 4.24 | 0 | 0 | |

| Christian People's Party | 209,697 | 1.99 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peruvian Nationalist Party | 177,984 | 1.69 | 0 | 0 | |

| Broad Front | 127,844 | 1.21 | 0 | –1 | |

| National United Renaissance | 101,822 | 0.96 | 0 | 0 | |

| Direct Democracy | 95,594 | 0.91 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 10,552,139 | 100.00 | 5 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 10,552,139 | 59.73 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 7,112,968 | 40.27 | |||

| Total votes | 17,665,107 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 25,212,354 | 70.07 | |||

| Source: ONPE | |||||

References

- ^ "Presentación de Resultados Elecciones Generales y Parlamento Andino 2021". resultados.eleccionesgenerales2021.

- ^ "Presentación de Resultados Segunda Elecciones Presidencial 2021". resultados.eleccionesgenerales2021.

- ^ "A record 22 candidates to square off in Peru's April presidential election". Reuters. 23 December 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Peru election: socialist Pedro Castillo claims victory ahead of official result". The Guardian. 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Peru Nervously Awaits Outcome Nine Days After Presidential Vote". International Business Times. 16 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Peru election race tightens as Fujimori gains, poll shows". Reuters. 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "In Peru's Presidential Election, the Most Popular Choice Is No One". The New York Times. 12 April 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Alemán, Eduardo; Ponce, Aldo F.; Sagarzazu, Iñaki (2011). "Legislative Parties in Volatile, Nonprogrammatic Party Systems: The Peruvian Case in Comparative Perspective". Latin American Politics and Society. 53 (3): 57–81. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2011.00125.x. ISSN 1548-2456.

- ^ Peru IFES

- ^ Resultados Congresales ONPE

- ^ "Andean Parliament". International Democracy Watch. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ "Fragmented Congress will facilitate reform in Peru". Emerald Expert Briefings. oxan–db (oxan–db). 1 January 2020. doi:10.1108/OXAN-DB250320. ISSN 2633-304X.

- ^ "Peru's Vizcarra faces challenges in year two". Emerald Expert Briefings. oxan–db (oxan–db). 1 January 2019. doi:10.1108/OXAN-DB242698. ISSN 2633-304X.

- ^ a b c "Perú.- El Congreso rechaza la reforma constitucional y el adelanto electoral propuestos por Vizcarra". notimérica (in Spanish). 29 September 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ "Peru's Vizcarra proposes early elections, opposition cries foul". Reuters. 28 July 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Elections Show Fissures in Peru's Political Institutions". Finch Ratings. 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Peru is out of the emergency room, but the prognosis remains guarded". The Global Americans. 4 December 2020.

- ^ "El exportero de Alianza George Forsyth gana alcaldía de La Victoria, en Lima". La Vanguardia. 8 October 2018.

- ^ de 2020, 12 de Octubre. "George Forsyth renuncia a la Alcaldía de La Victoria de cara a las elecciones de 2021". RPP Noticias.

- ^ "Restauración Nacional confirmó inscripción de George Forsyth al partido, que ahora se llamará Victoria Nacional". www.elcomercio.pe. 23 September 2020.

- ^ RPP Noticias, Redacción. "Elecciones 2021: Pedro Castillo, el dirigente magisterial que busca hacerse un lugar desde la izquierda [Perfil]". rpp.pe. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ a b J. Angelo, Paul J.; Mauvais, Chloé (1 June 2021). "Will Peru's Polarized Election Bring More Instability?". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Buenos Aires Times | Inequality fuels rural teacher's unlikely bid to upend Peru". Buenos Aires Times. Bloomberg. 3 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Herrada, Diego Pajares (23 December 2020). "Elecciones 2021: Pedro Castillo, el dirigente magisterial que busca hacerse un lugar desde la izquierda [Perfil] El Poder en tus Manos". rpp.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Fernández Calvo, Lourdes. "Minedu: huelga de maestros tuvo mayor impacto en cinco regiones". elcomercio.pe. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Tribunal peruano ordena liberar a Keiko Fujimori". RFI. 1 May 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "El voto de Keiko | elmundo.es". El Mundo. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Noriega, Carlos. "Un tribunal anuló la prisión preventiva de Keiko Fujimori | En una causa que enfrenta la excandidata peruana por lavado de activos". Página/12. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Peru election: Keiko Fujimori concedes defeat After narrow victory,". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "MEGAPOST: Cronología de las notas de Marcelo Odebrecht sobre Keiko Fujimori". Útero.Pe.

- ^ "Fujimori vows to pardon father if elected Peru president". France 24. 18 January 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Andina Noticias, Difusión (27 January 2021). "Elecciones 2021: conoce el perfil de Yonhy Lescano, candidato de Acción Popular". andina.pe. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Fernández, Liubomir (1 February 2021). "Elecciones 2021: Para analistas, Yonhy Lescano tendría el apoyo de puneños". larepublica.pe. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Verónika Mendoza es elegida presidenta del movimiento Nuevo Perú | POLITICA". El Comercio (in Spanish). 11 December 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Dosek, Tomas; Paredes, Maritza (3 June 2016). "Peru might elect an authoritarian president. These four maps tell you why". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ Taj, Mitra; 30 September 2016. "AQ Top 5 Politicians Under 40: Verónika Mendoza". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Noticias, RPP. "Rafael López Aliaga anuncia su candidatura a la Presidencia por Solidaridad Nacional". rpp.pe.

- ^ "Candidato de la ultraderecha peruana es acusado de golpista por sus oponentes". EFE (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Noticias, Informáte Perú. "Rafael López Aliaga anuncia su candidatura presidencial y dice que será el Bolsonaro peruano". informateperu.pe.

- ^ "Candidato ultraconservador peruano pide destituir al presidente Sagasti". Noticieros Televisa (in Spanish). 9 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ PERÚ, Diario La República. "Solidaridad Nacional cambia de nombre a Renovación Popular". larepublica.pe.

- ^ "Extreme Right Rises In Peruvian Politics". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Herrada, Diego Pajares (23 December 2020). "Elecciones 2021: Rafael López Aliaga, el exregidor provincial de Lima que quiere llegar a Palacio [Perfil] El Poder en tus Manos". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ PERÚ, Diario Gestión. "Hernando de Soto se inscribió como militante de Avanza País junto al empresario Carlos Añaños". gestion.pe.

- ^ Burt, Jo-Marie (25 September 2007). "Peru: Facade of Democracy Crumbles". NACLA. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ Borda, Luis (8 May 2016). "Hernando de Soto: "Alberto Fujimori fue víctima de la seducción de Montesinos"". RPP (Peru) (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ "De Soto says Fujimori backs Peru anti-poverty plan". Reuters (in German). 26 May 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ Abanto, Andrea (22 November 2020). "Politóloga sobre Hernando de Soto en Avanza País: "No creo que les interese la ideología"". larepublica.pe.

- ^ "Julio Guzman". Peru Reports. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Julio Guzmán: JNE lo dejó fuera de la carrera electoral". El Comercio (in Spanish). 9 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Sagasti, Francisco (15 November 2020). "Francisco Sagasti - Biography and Resume". franciscosagasti.com. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Dube, Ryan (16 November 2020). "Peru's Congress Chooses Lawmaker Francisco Sagasti as Next President". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Gestión, Redacción (20 January 2020). "Julio Guzmán: huyó y dejó sola a dirigente en departamento tras confuso incendio en Miraflores". gestion.pe. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ LR, Redacción (11 February 2020). "Urresti: más de 500.000 votos... ¿por carisma o autoritarismo?". larepublica.pe.

- ^ "Elecciones 2020: Daniel Urresti es el candidato más votado". 27 January 2020.

- ^ "El Partido Nacionalista Peruano retira la candidatura presidencial de Daniel Urresti". La Vanguardia.

- ^ Editorial (1 June 2015). "Sala Penal dispuso abrir juicio a Urresti por crimen de Bustíos". larepublica.pe (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2020.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- ^ CORREO, NOTICIAS (5 October 2018). "Lima: Daniel Urresti es absuelto del asesinato del periodista Hugo Bustíos ( | NOTICIAS CORREO PERÚ". Correo.

- ^ RPP Noticias, Política (23 November 2013). "Bayly: Humala encabeza Gobierno mediocre y Maduro tiene los días contados". rpp.pe. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ Ideele, Revista (8 April 2016). "Lo bueno, lo malo y lo feo de Humala + 2". revistaideele.com. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ "El Comercio: Daniel Salaverry, el vocero que cayó del norte [PERFIL]".

- ^ RPP Noticias, Redacción (8 September 2019). "Daniel Salaverry afirma que Keiko Fujimori le dijo que se preparara para convocar a elecciones". rpp.pe. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Martín Vizcarra confirma que postulará al Congreso por el partido Somos Perú | NNDC | PERU". Gestión (in Spanish). 28 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Peru candidates banned from election". 9 March 2016 – via www.bbc.com.

- ^ Perú, Redacción El Comercio (12 June 2020). "APP lleva la delantera". El Comercio Perú.

- ^ El Comercio, Redacción (23 October 2020). "Elecciones 2020: Alberto Beingolea anuncia su precandidatura en el PPC". elcomercio.pe.

- ^ Andina Noticias, Política (22 December 2015). "Alberto Beingolea anuncia que no irá a la reelección en el Congreso". andina.pe.

- ^ ONPE (2 November 2018). "ONPE Resultados al 100%". onpe.gob.pe.

- ^ Andina Noticias, Walter Gonzalo Arcasi Mariño (28 September 2020). "Elecciones 2021: pugnas en el Frente Amplio por precandidatura de Marco Arana". gestion.pe. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ Andina Noticias, Difusión (27 January 2021). "Elecciones 2021: conoce el perfil de Marco Arana, candidato del Frente Amplio". andina.pe. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Andina Noticias, Difusión (27 January 2021). "Elecciones 2021: conoce el perfil de Rafael Santos, candidato del Perú Patria Segura". andina.pe. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ RPP, Noticias (23 December 2020). "Elecciones 2021: conoce el perfil de Rafael Santos, candidato del Perú Patria Segura". rpp.pe. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ RPP, Noticias. "Elecciones 2021: José Vega, el promotor de la vacancia presidencial que quiere llegar a Palacio de Gobierno [Perfil]". rpp.pe. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ RPP, Noticias (10 October 2020). "José Vega de Unión por el Perú: "Liberación de Antauro Humala está en curso"". peru21.pe. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Andina, Noticias. "Ciro Gálvez solicita inscripción de su candidatura por Renacimiento Unido Nacional". andina.pe. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ Exitosa, Noticias. "Gálvez y Zolla, nueva alianza para las elecciones". exitosanoticias.pe. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ RPP Noticias, Redacción. "Elecciones 2021: Andrés Alcántara busca ganar su primera elección para reformar la Constitución [Perfil]". Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Canal N, Actualidad (11 February 2021). "Andrés Alcántara: Candidato de Democracia Directa apuesta por una nueva Constitución". Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Andina Noticias, Carlos Lezama (27 January 2021). "Elecciones 2021: conoce el perfil de Andrés Alcántara, candidato por Democracia Directa". Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Castro, Jonathan (16 January 2021). "Elecciones 2021: El Apra decide retirar la candidatura presidencial de Nidia Vílchez". elcomercio.pe. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Gestión, Redacción (23 December 2020). "Elecciones 2021: Contigo presenta queja ante el JNE por fallas para inscripción de listas". gestion.pe. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Perú21, Redacción (26 December 2020). "Elecciones 2021: declaran improcedente pedido de Perú Nación para inscripción de lista presidencial". peru21.pe. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Gestión, Redacción (24 December 2020). "Elecciones 2021: Fernando Olivera queda fuera de la carrera electoral". elcomercio.pe. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ El Comercio, Redacción (26 December 2020). "Elecciones 2021: rechazan inscripción de fórmula presidencial de Todos por el Perú, liderada por Fernando Cillóniz". elcomercio.pe. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Radio RCC Tacna, Redacción (29 December 2020). "Fórmula presidencial de UPP, encabezada por José Vega, fue declarada improcedente". rcctacna.com. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ El Comercio, Redacción (6 February 2021). "JNE revocó exclusión de plancha presidencial de José Vega y dispuso verificación de hojas de vida de UPP". elcomercio.pe. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Gestión, Redacción (8 January 2021). "César Acuña excluido de plancha presidencial de APP por JEE". gestion.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Gestión, Redacción (5 March 2021). "Rafael López Aliaga y George Forsyth siguen en carrera electoral tras decisión del JNE". Peru21 (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Andina, Noticias (22 January 2021). "Elecciones 2021: JNE resuelve que César Acuña continúe en carrera". gestion.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Garay, Shirley (4 February 2021). "Elecciones 2021 | JEE declara fundada tacha contra candidatura de Daniel Urresti a la Presidencia". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ RPP Noticias, Redacción (18 February 2021). "Elecciones 2021: JNE revoca tacha contra la candidatura de Daniel Urresti a la Presidencia". rpp.pe. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Elecciones presidenciales 2021 | Elecciones 2021: JEE Lima Centro 1 concluye excluir a George Forsyth como candidato presidencial | POLITICA". Peru21 (in Spanish). 11 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Gestión, Redacción (5 March 2021). "Rafael López Aliaga y George Forsyth siguen en carrera electoral tras decisión del JNE". Peru21 (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Excluyen a López Aliaga por ofrecer que donará su remuneración si asume la Presidencia | POLITICA". Peru21 (in Spanish). 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Gestión, Redacción (25 February 2021). "JEE excluye de la contienda a candidato presidencial de Victoria Nacional, George Forsyth / También Ciro Gálvez". peru21.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d Sonneland, Holly K. (1 June 2021). "Contrasting Platforms in Peru's Presidential Runoff". AS/COA. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b Allen, Nicolas (1 June 2021). "Pedro Castillo Can Help End Neoliberalism in Peru". Jacobin. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Odebrecht: Gigantic corruption scandal shows no sign of waning". BBC News. 17 April 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Franklin Briceno; Joshua Goodman (10 February 2017). "Manhunt for Peru's Fallen Ex-President Starts in California". ABC news. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ^ "Peru's leader resists pressure to resign". Bbc.com. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Meet the Candidates: Peru". Americas Quarterly. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b "'Mano dura', el plan de gobierno de Keiko Fujimori para Perú". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Taj, Mitra. "Peru president proposes referendum on political, judicial reform". Reuters. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Ayma, Diego (20 October 2020). "Presentan nueva moción de vacancia contra el Presidente de la República" [They present a new vacancy motion against the President of the Republic] (in Spanish). RPP Noticias. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Peru's swears in new leader as political turmoil hits nation". Star Tribune. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "EN VIVO | Junta de Portavoces se reúne para evaluar renuncia de Manuel Merino tras las muertes de dos jóvenes en la Marcha Nacional | Ántero Flores-Aráoz | Congreso de la República | Vacancia presidencial". RPP (in Spanish). 15 November 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Allen, Nicolas (1 June 2021). "Pedro Castillo Can Help End Neoliberalism in Peru". Jacobin. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "'No Chavismo here': Peru socialist candidate Castillo seeks to calm jittery markets". Reuters. 22 April 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Santaeulalia, Inés; Fowks, Jacqueline (12 April 2021). "Perú se encamina a una lucha por la presidencia entre el radical Pedro Castillo y Keiko Fujimori". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "¿Quién es Pedro Castillo? La gran sorpresa de la elección en Perú". Página/12 (in Spanish). 13 April 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Palacios, Oswaldo (6 April 2021). "Pedro Castillo: "Vamos a desactivar el Tribunal Constitucional en el acto", porque sirve para defender la gran corrupción". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Peru's Revolt Is About More Than Corruption". Jacobin. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Meet the Candidates: Peru". Americas Quarterly. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "Elecciones 2021 | Mi visión del país, por Keiko Fujimori | Fuerza Popular | ELECCIONES-2021". El Comercio (in Spanish). 6 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "COVID Live Update: 174,448,269 Cases and 3,754,101 Deaths from the Coronavirus - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Battling COVID-19 proving deadly for Peru's doctor corps". Associated Press. 27 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Covid: Why has Peru been so badly hit?". BBC News. 1 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Medics go on hunger strike in Peru amid Covid-19 second wave". CNN. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "George Forsyth pide al Gobierno que "se active" el COEN para hacer frente a segunda ola del COVID-19 nndc | POLITICA". Peru21 (in Spanish). 29 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Garay, Shirley (5 February 2021). "Elecciones 2021 | Verónika Mendoza: "El Gobierno debe dejar de hacer las cosas al revés"". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Verónika Mendoza critica la comercialización de vacunas COVID-19 por entes privados - Caretas Política". Caretas (in Spanish). 11 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Hernando de Soto presentó 'Gabinete de oposición' para dar propuestas al Gobierno". rpp.pe (in Spanish). 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Hernando de Soto presentó a los miembros «del gabinete de oposición»: ¿Quiénes son?". caretas.pe (in Spanish). 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Quigley, John (20 August 2020). "Peru Leads Global Economic Crash With 30.2% Quarterly Drop". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Peru seemed to do everything right. So how did it become a Covid-19 hotspot?". CNN. 26 May 2020.

- ^ O’Boyle, Brendan (19 August 2020). "This Soccer Star Could Be Peru's Next President". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Los Candidatos Responden: George Forsyth - Caretas Política". Caretas (in Spanish). 3 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Los candidatos responden: Keiko Fujimori - Caretas Política". Caretas (in Spanish). 29 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Venezuela Migration Crisis - Peru: Second Largest Destination for Venezuelan Migrants - Peru". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "¿Por qué está militarizada la frontera entre Ecuador y Perú?". BBC News (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Peru's crime worries tainting Venezuelans who want to work". Associated Press. 6 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "George Forsyth cuestiona al Gobierno por descontrol en entrada de extranjeros por la frontera norte". Diario Expreso. 23 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Test TOPES: Verónika Mendoza, a partir del plan de gobierno de Juntos por el Perú, es demócrata, semicontrolista y liberal - Caretas Política". Caretas (in Spanish). 31 January 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "Either way, it's bad news; Bello". The Economist: 31. 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Neoliberal or Marxist? Polarized Peru faces volatile future either way". euronews. 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Taj, Mitra (11 April 2021). "In Peru's Presidential Election, the Most Popular Choice Is No One". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ a b Puente, Javier (14 April 2021). "Who is Peru's Frontrunner Pedro Castillo?". North American Congress on Latin America. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Burt, Jo-Marie (5 June 2021). "Peru's military say Shining Path insurgents killed 16 civilians. Others are not so sure". The Washington Post.

The Fujimori campaign seized upon the Vizcatán massacre to reiterate the “Castillo-as-extremist” narrative, pointing to alleged ties between Castillo and a Shining Path front group, MOVADEF, to suggest that Castillo bore some responsibility for the gruesome killings.

- ^ a b c Freier, Luisa Feline; Castillo Jara, Soledad (13 January 2021). ""Terruqueo" and Peru's Fear of the Left". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Peru polarized by two social conservatives in presidential runoff". Public Radio International. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Keiko Fujimori would be 'lesser of two evils' as Peru president, says Nobel prize author". the Guardian. 18 April 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allen, Nicolas (1 June 2021). "Pedro Castillo Can Help End Neoliberalism in Peru". Jacobin. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Escalante, Claudia (22 May 2011). "Mario Vargas Llosa: La peor opción es la de Keiko Fujimori". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ PERU21, NOTICIAS (24 September 2014). "Vargas Llosa sobre Keiko: 'No quiero que sea presidenta la hija de un asesino' | POLITICA". Peru21 (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ Noriega, Carlos (19 April 2021). "Perú: la derecha neoliberal se alía con el fujimorismo autoritario | Vargas Llosa dio su apoyo a Keiko Fujimori para el ballottage". PAGINA12. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h O’Boyle, Brendan (3 May 2021). "Pedro Castillo and the 500-Year-Old Lima vs Rural Divide". Americas Quarterly. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Sonneland, Holly K. (1 June 2021). "Poll Tracker: Peru's 2021 Presidential Runoff". AS/COA. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Commies, crooks and bloodshed; Peru's election". The Economist: 30. 29 May 2021.

- ^ "Son of the soil Pedro Castillo promises a presidency for Peru". the Guardian. 5 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ News, A. B. C. "Students' struggles pushed Peru teacher to run for president". ABC News. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Dismissal of news director of Peru's main television stations worsens credibility crisis in the press during polarized elections". Knight Center for Specialized Journalism. 19 May 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ LR, Redacción (10 May 2021). "Historia de una arbitrariedad, por Gustavo Mohme Seminario". larepublica.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Cuarto Poder: América TV despide a periodistas que denunciaron censura". Libero. 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Galarreta sobre reunión de Keiko Fujimori con Clara Elvira Ospina: "Fue de coordinación. Nos hemos puesto de acuerdo sobre los programas, tiempos y debates, nada más"". Diario Expreso. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ LR, Redacción (9 June 2018). "Terrorista "José" amenaza con más ataques a las fuerzas del orden". La República (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Zapata, Ralph (24 May 2021). "Violencia en el valle de la droga: grupo narcoterrorista de 'José' es acusado de acribillar a 16 personas". OjoPúblico (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ a b Caretas (14 May 2021). "La peligrosa «camarada Vilma»". www.caretas.pe. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Andina (24 May 2021). "Jefe de Policía Nacional confirma muerte de 18 personas en el Vraem". andina.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Al menos 14 personas mueren en Perú en un ataque que las autoridades atribuyen a Sendero Luminoso" (in Spanish). BBC News Mundo. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ El Comercio (24 May 2021). "Vraem: 18 personas fueron asesinadas por miembros de Sendero Luminoso". elcomecio.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Al menos 14 personas mueren en Perú en un ataque que las autoridades atribuyen a Sendero Luminoso" (in Spanish). BBC News Mundo. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Keiko Fujimori sobre el atentado en el Vraem: 'Lamento profundamente que nuevamente actos sangrientos estén ocurriendo en nuestro país'". El Comercio (in Spanish). 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Castillo, Sophia (24 May 2021). "Pedro Castillo sobre ataque en el VRAEM: "Insto a la Policía a que haga investigaciones inmediatas"". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Vladimir Cerrón afirmó que "la derecha necesita de Sendero para ganar"". Caretas (in Spanish). 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Chavez, Adriana (24 May 2021). "Presidenta del Consejo de Ministros y Ministra de Defensa condenan atentado en el Vraem: "No quedará impune"". RPP (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "¿Cuántos observadores internacionales vigilarán la segunda vuelta electoral?". Ojo Público (in Spanish). 4 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Collyns, Dan (8 June 2021). "Peru elections: Fujimori's fraud claims criticised as rival's narrow lead widens". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Keiko Fujimori alleges fraud in tight Peru election". France 24. 8 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ ""We must defend popular sovereignty in Peru"". Progressive International. 8 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Perú: Castillo se proclama vencedor sin los resultados definitivos del conteo oficial". France 24. 9 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Fujimori seeks ballots annulled as leftist Castillo leads in Peru's presidential vote". France 24. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.